Afro-American’s archives reveal the fight for Black women’s right to vote — and the battles beyond

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Reynolds Journalism Institute or the University of Missouri.

The Black women of Baltimore weren’t content to simply celebrate the ratification of the 19th Amendment, 100 years go this month. They intended to use its power.

With only two months to prepare, suffrage leaders immediately began organizing to educate other Black women about how they could take advantage of this new right in the upcoming 1920 US presidential election. They held meetings for new women voters every Thursday at 8 p.m. at the YWCA. They wrote news stories and columns in the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper. They reserved time at the end of Sunday sermons to alert churchgoers, and they held suffrage meetings to promote the cause.

“We women are especially bitter against the type of white politicians who said that we would not know a ballot if we saw one coming up the street,” said one group president at a Baltimore meeting of the Colored Women’s Suffrage Club. “We must register to vote, and we must vote to rebuke these politicians.”

This is the kind of determination that Savannah Wood, archives director at the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper, found as she researched the suffrage era in the newspaper’s archives. Now Wood has gathered these newspaper clip files and historical documents in a new book: “To The Front: Black Women and The Vote,” published by the Afro-American newspaper and its charity arm, Afro-Charities Inc.

This lavishly illustrated, 118-page volume is a keepsake publication that draws deeply from the rich archives of the Afro American, which has been publishing continuously since it was founded in 1892. And it’s these archives, carefully preserved and tended over 128 years by the family of its founder, that made this book possible.

The book was the publisher’s idea, said Wood. “She wanted to do something to honor the 100 year anniversary of Black women in the suffrage movement. Because the Afro goes so far back, many of those documents about this would be in our archives. So this is a great place to look for this material.”

“We’re really trying to celebrate the people who were involved in this whose names might not be recognized,” Wood said.

In some ways the book is a labor of love for Wood and the publisher, both journalism royalty as descendants of John Murphy, who founded the newspaper in 1892. The family has kept it running ever since.

The book, supported through a grant from Facebook, includes not only original news stories and photos from the time, but also profiles of key women who were deeply involved in the years of struggle to gain the right to vote.

They include Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, a poet who lectured on anti-slavery in the 1850s and was a founding member of the American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Association of Colored Women. “As much as white women need the ballot,” she told a New York convention of this group after touring conditions in the South, “Colored women need it more.”

And Ida R. Cummings, the first African American kindergarten teacher in the Maryland public school system in 1901.

And Martha Elizabeth Howard Murphy, a founder and leader of the Colored YWCA in Baltimore. Murphy played a key role in helping her husband start the Baltimore Afro American, using money from the sale of family farmland as seed funding.

The book includes numerous stories and profiles of recent and modern-day Baltimore women who continued the work for justice.

Women like Dr. Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, who co-founded the Association of Black Women Historians in 1979, and who researched and advocated for recognition of African American women’s struggles and triumphs.

And Dr. Martha S. Jones, a renowned historian, the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and a professor of history at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Plus groups like the Du Bois Circle, first formed in 1906 by five black Baltimore women, and still going more than a century later. The book highlights key figures in the Baltimore Ceasefire movement that began in 2017, along with Nicole Hanson, executive director of Out for Justice, a group working to restore voting rights to former felons.

For Wood, working in the Afro’s extensive archives was one of the more fascinating parts of the journey. “There’s just so many great articles,” she said.

Combing through the collections, mostly housed now at Morgan State University, required some mental gymnastics, including learning the terminology of the time.

“At first, I was searching for ‘women’s suffrage’,” Wood recalled. “But what was often used was ‘woman suffrage,’ no plural and possessive.”

“And then realizing I had to look for women under their husband’s name… Picking up on those cues as you go through the research took time.”

The book is packed with comments and questions about suffrage through the eyes of African American residents in Baltimore at the time, as reflected in the pages of their newspaper.

“What good will it do for women to vote?” asked a reader named Eva in an October, 1920 letter to Augusta Chissell, who began writing regular Q&A columns in the Afro-American for readers to educate them on voting rights and procedures.

“Just what it does for men,” Chissell wrote in response. “It will give women power to protect themselves in their persons, property, children, occupations, opportunities and social relations. It will enable them to get done what ought to get done.”

The book originally was intended to be one part of a wider effort that included public events designed to encourage voter registration and turnout among Baltimore’s African American residents in this year’s presidential election. The book still reflects some of these plans, including a chapter on performances of “Casting The Vote,” a play that dramatizes the need to use voting power to pursue justice, and a chapter on the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund.

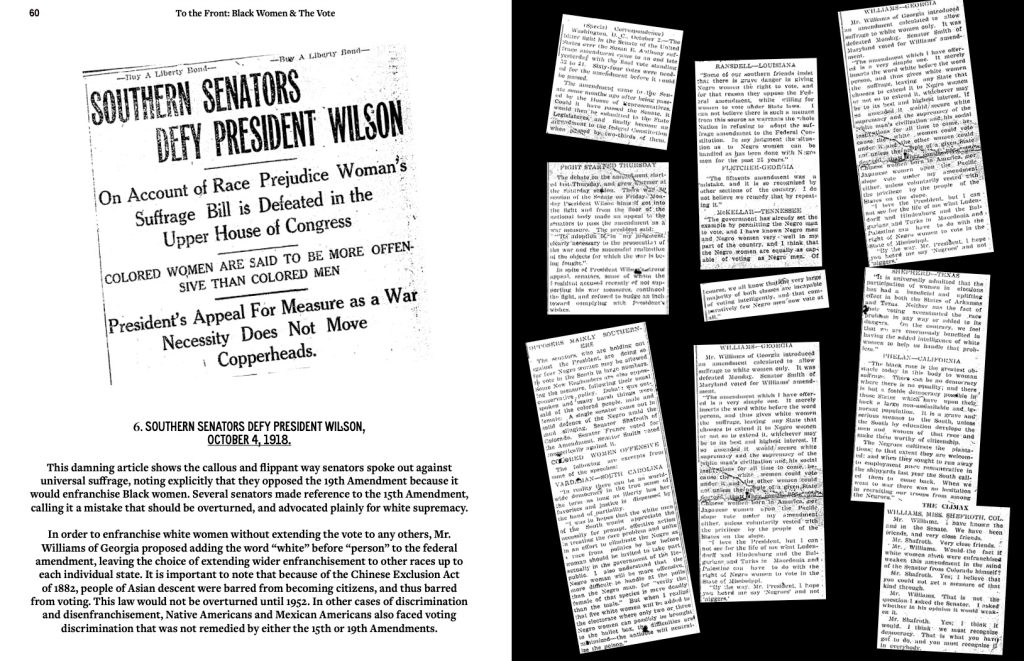

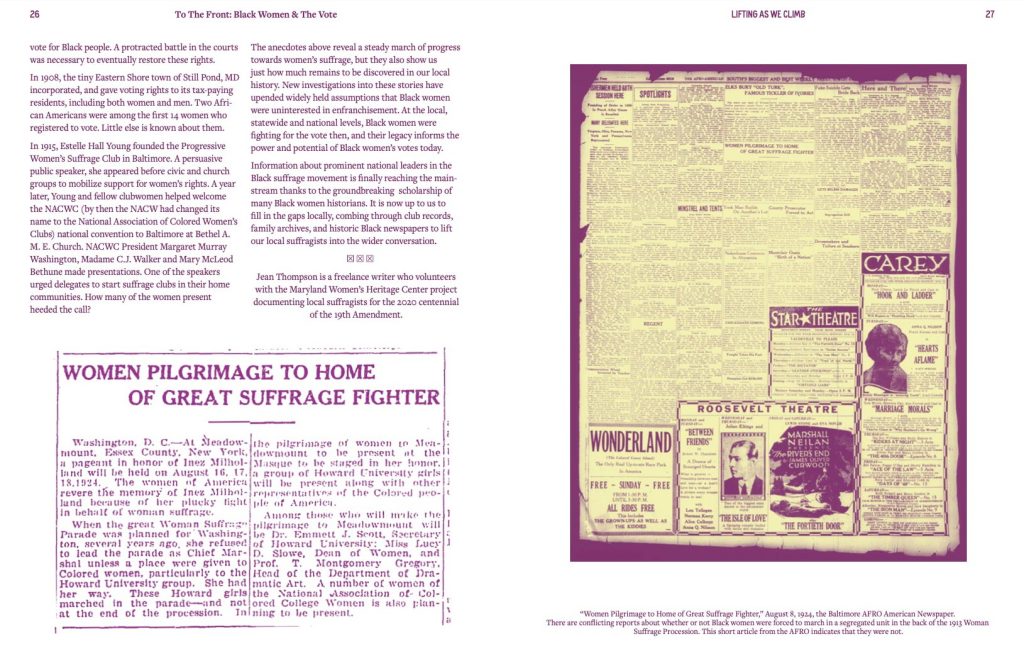

But it’s the suffrage-era news clips that form the heart of this volume. They show what African American people living in Baltimore read at the time in their newspaper, which reported on years of Jim Crow restrictions to keep Blacks from voting and efforts to restrict suffrage to white women only.

It’s the words of Baltimore’s African American suffrage leaders that ring most clearly across the intervening century.

“I say, then, that justice is not fulfilled so long as woman is unequal before the law,” said Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, in a speech to a white suffrage group in New York that is reproduced in the book. “We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul.”

For more

- The book, “To the Front: Black Women and The Vote,” is available as a high-quality print volume (118 pages), or as a downloadable PDF (90 pages). To order, go to this link: https://tothefront.us/

- Wood is curating an exhibit titled “Close Read,” which showcases images by Wood and two other artists inspired by this research in the Afro archives, Shan Wallace and Akea Brionne Brown. The show opens the week of Aug. 20 at the Click + Connect Gallery in Baltimore, and is viewable from the street so patrons can maintain social distancing. Here’s a link for the gallery:https://bmoreart.com/connectcollect

- Here’s where to find the Baltimore Afro American’s online edition: https://afro.com/