Building a culture of great visuals

Boyzell Hosey, Deputy Editor of Photography, faces new challenges at the Tampa Bay Times in planning the daily visual report. He directs a significantly smaller photo staff than a decade ago in addition to the added burden of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. But the plan boils down to the same principle as always, he said. “You’ve got to talk about what’s best for the story.”

“Picture editing is so important,” he said. “I think it’s actually more important right now than the actual photographer’s job. Because new platforms make visuals crucial. Everyone in the newsroom needs to understand why photographs are important for the story and how to do the best with whatever you’ve got.”

“You need to talk about the story ahead of time and you need the right people at the table,” he said.

Before the shutdown, it was easy for Hosey to walk the newsroom to talk to colleagues and find out what stories were coming up, he said. That approach matched his personal style.

Now, with colleagues working from home, “I’m searching around in the computer system, messaging people,” he said. “It’s like I am mining bits of information all of the time so that I can see possibilities and get ahead of the ballgame.” Six months into working from home, “I am just now figuring out a decent rhythm for engaging my colleagues.” he said.

Just a few years ago, The Tampa Bay Times had more than a dozen photographers and five picture editors. With the industry downturn that started in 2008, the photo staff is now eight people, including Hosey.

“I don’t think our issue at this point is not having enough photographers — I mean, it would be nice to have more photographers, don’t get me wrong, but it’s not going to happen,” he said. “It’s too expensive to house a large photography staff these days. So, now you’re down to a handful of people to try to do your best visual journalism.”

Hosey worries when he sees editing decisions that are just not in the best interests of the reader.

“Where a lot of newsrooms run into problems, especially smaller news organizations,” said Hosey, “is that they view photographers or picture editors as, basically, service departments. They’ll say, “I need an image of x, y and z. So, someone will go get a photo of x, y and z.”

“Visual journalism is all about the story,” said Suzette Moyer, Hosey’s former colleague at the Tampa Bay Times who is now senior design director at The Washington Post.

“Visual editors need to have a seat at the table as equals in the process,” said Hosey, “talking about the content.”

I asked the two veteran visual leaders to offer advice for small news organizations or non-profits as they try to make the very best visual decisions with the resources they have. Both have worked in newsrooms of many shapes and sizes over the last 30 years. And both have led extraordinary teams of visual journalists.

Lack of conversation = Missed opportunity

Images are often the last thought when they should be one of the first. That’s why we end up saying “Okay, we’ve got this story, but no photo. Let’s look for a stock photo image to represent this, that or the other,” said Hosey. “To me that is a terrible fallback, right? Not a good one. Because you’re not really taking advantage of what a visual narrative can offer.”

“And a stock photo usually feels canned and just inappropriate,” said Moyer. “People are much more engaged by photos of real people doing something that’s really happening rather than a fake moment. It’s best to avoid stock images when at all possible.”

Using the resources you have

“These days, we’re not trying to do more,” said Hosey, “we’re trying to go deeper. If we need to send a photographer across the state for a good story, that’s what we’re going to do. We might have to let another thing go, but we need to make good choices in support of a good story.

“If you want a great photo essay, then you really need to hire a photojournalist to do it right,” said Hosey. “You really do. If you want more than a few photos to really carry this story, you need someone who knows what they’re doing,” said Hosey.

“But, if the story is relatively straightforward, if you just need one or two good images. There is a basic formula that most people can use, even with a cell phone,” said Hosey. “Get a photo of the person, get a photo that gives a sense of place, and maybe a detail shot. The basic formula will work for most stories.”

“Most importantly, take the chance to coach a little,” said Hosey. “Even if it’s just a minute as the reporter is walking out the door. You need to talk about what the photo should be. What do we need from this particular photo that helps the story?”

“I want you to get the best possible visuals, whether a writer is going to shoot it, a freelancer or one of the staff photographers is going to shoot it,” said Hosey. “But, we need to have a conversation around the ultimate goal.

Moyer asked Hosey, “If a reporter goes out to photograph something, do you tell him to take as many photos as he can? Or do you think it’s better to hone-in on a moment?”

“I don’t really believe in the shotgun approach,” said Hosey, “because you can just end up getting a bunch of bad photos. It’s much better to be intentional about the photo you’re trying to take.”

That brief coaching conversation goes a long way, said Hosey. For example: “We won’t have a photographer there at the press conference, but the family’s going to be there. So, look for a moment between the family members. Watch for emotion.’ ”

“You mentioned detail shots,” said Moyer. “I always love when a photographer includes, like, a photo of the subject’s hands in addition to a portrait — or a pin on a person’s lapel. “Details make the reader feel like they are there, in person.”

Photo opportunities will be missed. That’s when resourcefulness kicks in.

“I’ll be looking at a story on the weekend budget, and there are no photos. If there had been communication about it early on, we could have really done something with it,” said Hosey. “But I always want folks in the newsroom to let me know what’s up, then we can work out a solution together. We can talk through these things.”

File photos from an archive can be made relevant again by freshening up a caption with a bit of reporting, said Moyer. “Maybe it’s a new comment in the caption from someone close to the story. It takes time, sure, but that’s just good editing.”

“Then, there is a thing called crowd-sourcing, right?” said Hosey. “It was almost unimaginable decades ago that we’d look to our subjects to provide us with photos. But now, it’s not out of the question to perhaps ask a subject if they have photos. I think crowd-sourcing, done in the right way, is a good thing. We can, at least, vet those photos when they come in.”

The two agree on the necessity for strong communication between photo and design. A designer needs a variety of options, said Moyer. “What will play best large and small … what will draw the most attention paired with the headline,” she said.

“Most people aren’t really trained to think about how that image is going to serve on different platforms,” Hosey said. “For example, I’m going to want to pick a different photo that will run four or five columns wide in the printed paper than I will choose for this two two-inch screen. I might be looking at the detail shot, or even something tighter.”

Case study: Extending the impact of a visual story

Often, when photos or videos are published, the story is finished and the images never really surface again. But new platforms offer powerful, visual reach to new audiences if newsrooms make the effort.

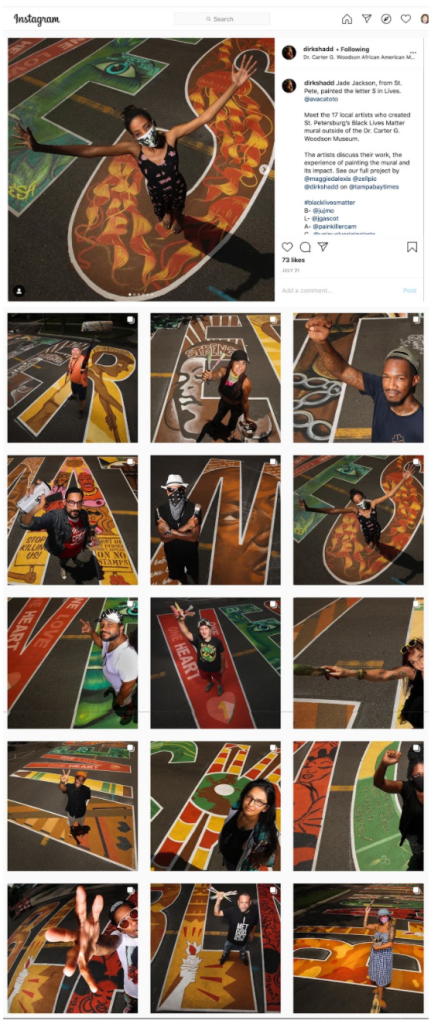

Living a thousand miles away, I learned about a story in St. Petersburg, Florida when I saw it on Instagram. A great example of using social media for powerful, visual storytelling, it made me feel like I’d seen it in person.

“So many cities across the country were doing murals in honor of “Black Lives Matter,” with the letters on the road,” said Moyer. “But the one in St. Pete was really the most detailed of anything I saw. It was so intricate. And you really needed to be able to see the detail of the painting.”

Coverage included beautiful portraits of each of 16 artists who worked to create a mural in front of the Carter G. Woodson African American Museum. After the story ran in print and online, the social media storytelling included a drone video, social media posts with photos, quotes, profiles of each artist, a link to the site and tags linking everyone involved in the project.

“It befuddles me,” said Hosey, “the fact that we’re working in such visual mediums today — with so much opportunity to do things with visuals, and we sometimes have an antiquated way of doing things. But I feel really good about this project.”

Without the effort from the Times photo staff, the visual story might have reached only a fraction of the audience.

“That was probably ‘textbook’ in the way it all came together, said Hosey. “It was a huge community event that we documented. I was just blown away by the community project and I thought that people really needed to see it. I ended up going live with a Facebook video story. And I said, ‘I guess I know what our next portrait project should be!’ ”

“Dirk called and said ‘Hey, let’s team up on this.’ And, we did,” said Hosey. “We engaged our social media team, and they took it to a whole other level. It all came about because we were, like, sharing the love. It was a great community story. Everyone who worked on it brought their strength to the table.”

“With social media, we don’t really have excuses anymore not to do our best work and get it out there — no more restrictions on the amount of space to show visuals,” said Hosey. “It’s just in different forms. With social media, it’s like having your own publishing platform.”

With all of the muralists who had been part of the project tagged, of course, they all saw it. And a lot of their followers saw it. That’s the power of social platforms. That attention to platform presentation of visuals really extended the reach of that project.

“It’s like that little community moment that just starts to spread, in service of the story,” said Moyer. “A local story that has a tie to a much more global story. Visuals are the mechanism for sharing.”

“We have to focus our conversations to the power of the image. The seeds need to be planted,” said Hosey. “The gateway to getting people to the content is through the images.”

With interviews like this one, we are building a toolkit of tips, resources and case studies for small media organizations to strong, visual storytelling. The training materials (and workshops) will be made available free of charge from NPPA and RJI. We’d like to hear from you. Give us your tips, your success stories, you wish list, or tell us how you’d like to be involved!