So you call yourself a journalist. What does that mean?

Reynolds Fellow Mike Fancher and students at the Missouri School of Journalism tackle the question of the century.

Mike Fancher was the executive editor at the Seattle Times for 20 years. This year, he’s a fellow at the Reynolds Journalism Institute, where he’s seeking to answer to some of the most important questions facing journalists today. In an atmosphere of multiplying blogs and citizen reporters, who really is a journalist? What are our standards for our work, and what do we stand for?

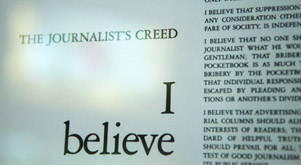

He’s starting with a foundation: “The Journalist’s Creed,” written almost a century ago by Walter Williams, the first dean of the Missouri School of Journalism. This simple but powerful list of values and principles guided journalists of the 20th Century. Now, it’s time for an update — a new code of ethics for a new era of journalists.

In November 2008, Fancher talked to the people perhaps most important to answering these big questions: future journalists.

The following is a conversation between Fancher and students at the Missouri School of Journalism. Fancher’s questions are bold. The student audience’s comments follow. (This discussion has been edited for clarity.)

In December 2007, I decided to retire from the Seattle Times after 30 years there — 20 of those as executive editor. I stayed around until the end of April doing a blog. I focused on the nexus between citizenship, journalism and technology. And how technology has changed the relationship between citizenship and journalism.

For the last couple of years, I had been giving public talks about, essentially, public service journalism. The vehicle I used to introduce this topic was The Journalist’s Creed. I first read it when I was a sophomore in high school working for my student newspaper.

During my 40 years at newspapers, I had the good fortune to work for two dailies: the Kansas City Star, when it was employee owned, and the Seattle Times, which is owned by a family there. Both of those newspapers subscribed to the principles of “public service journalism.” I was able to have this great career working for people who shared my values about what journalism was supposed to do.

In my recent speeches, I’ve voiced that I’m really fearful that this kind of journalism is at risk because of the business model of journalism is changing. Technology is changing the relationship between journalists and citizens.

So, we’ve started to think about the ways to express this 21st century creed – you know, the document. I think there’s a lot in there that’s kind of dated — and a lot in there is dated. But there’s also a lot that still pertains to journalists. I’m interested in the questions:

What is the profession of journalism? What is the future of the journalism profession?

And what’s not in this creed?

I’d like to hear from you. Think about this: Walter Williams wrote the creed in 1914. For a century, the creed’s journalistic ethics guided people like me. Our time has come and gone. It’s your time going forward. You know you’re the ones who need to think hard about this: What motivates, inspires, and guides you as you think about the career you want as a journalist?

That’s what this conversation today is all about.

I guess the distinction that we draw is between people who are doing journalistic things, and people, like us, who consider it our profession.

What else is different? There is this distinction between somebody who is doing this journalistic function, and somebody who is committing it. We’re clearly in a world where lots of people are doing lots of things that are journalistic functions. So, what sets a professional journalist apart? Or is there anything?

You still need ethics, For example, I read a technology blog — they do their best to differentiate between what they know and what’s rumor. They try to be ethical. They try to be clear about their sources. You need to maintain the ethics, the transparency, or else it looks like you’re in someone’s hands.

If you were writing a new creed, and included an expectation that journalists would practice transparency, or be transparent, what things would the journalist be expected to do?

We must be on the same level of the playing field and have some kind of dialogue with the readers. We try to show where our sources came from. I think transparency is going to be the big thing going forward. Anybody can get the information nowadays, for the most part. It’s about validating it, more than anything.

The concept of “conversation” may be perceived as part of accessibility. You’re no longer “looking down” upon your reader, or your audience, or citizens. You’re collaborating with them in the news process.

Hopefully to build community, to build better relationships. Many voices are commanding tremendous respect and audience accessibility. This makes us stop and think: To whom are we talking? How are we talking to them?

I also would encourage you to look at Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel’s book, The Elements of Journalism. They interviewed 3,000 or so journalists, asking them: What is journalism to you? Not does it have to be paid or unpaid. But what is journalism to you? It would be fun to compare the creed, because many of those principles are in here, right?

Accessibility can cover a lot of information, including portals, delivery of news – whether it’s paid or unpaid. But accessibility could be a responsibility.

One of my class readings described journalism of the 21st century as a service. The facts are just the facts. But journalists give readers services: You tell people how this affects them, and how they can act in response.

Also, if you’re transparent, you’re telling readers whenever something happens with the parent company. You’re very clear that, yes, we know, this is our parent company. We still have our own opinions. If you’re clear where you’re coming from and why you’re telling your readers these things, I think it also develops a bit of trust.

The creed talks a lot about public service. But what does that mean today, and how has it changed? I think that’s really important because you can look at public service two ways. Is it what the public wants? Or are we giving them what we think is good for them?

The line of the creed I really like, that is still relevant, is the first line: “I believe in the profession of journalism.”

In the 21st century, you have new forms of interaction, like blogs. Bloggers don’t necessarily have to understand all of the tenants of journalism, but they can still interact with the public and share information. The creed is still useful because it provides the division between who’s a journalist and who isn’t a journalist.

I also think, just from reading so many blogs, that it’s interesting how many of these arise organically. You’ll see

People instinctively determine which blogs they can trust and which ones they can’t.

Maybe we can define the role of the news organization as being able to get to the stories that citizens who aren’t part of this organization might not otherwise have the resources to get. A normal person on the street can’t get an interview with the White House press secretary. But, those of us at, say, a newspaper, would have more luck. It’s hard for people with another job to gather news. But that’s what we do – look for stories so that

We can provide readers with the information they want, but they can’t necessarily get on their own.

That’s a place where we can still be relevant.

That’s an interesting observation – the notion of the journalistic organization being a part of what defines a journalist, or at least gives that journalist special access. What’s happening with journalism organizations today, at least in the short run, is a lot of people who really want to be professional journalists may be working outside the context of the traditional organization.

I think you have to make yourself into a brand, due to the Internet. That’s what one sports journalist said at the Centennial (of the Missouri Journalism School in September 2008). He was saying it was odd that he felt he had to champion himself, because he still had the idea that the journalist was supposed to be invisible. The good thing is that the public is getting savvy to this.

Today, there is a sense that “sincerity,” or “authenticity” matters to people – whether you’re talking about politics or journalism. What would a creed have to say that keeps you honest – to be true to yourself? I think that’s what authenticity is all about. Is there anything that comes to mind that would bring you back to being true to yourself?

We need to keep in mind the balance between journalism and the business aspect. I know that journalism is obviously a business. We must be true to people in that sense.

We shouldn’t impede innovation in any way, but we also shouldn’t allow new technology to distract us to the point where we aren’t the watchdogs anymore.

My father just sent me a column by a journalist down in Houston today. He talked of the death of the newspaper. He wrote that it could be the death of true investigative journalism, and how that is what really informs the public – that it’s the greatest public service that we can offer.

If we allow new technology to distract us from the story, I see that completely undermining journalism. Everything we’re saying is the difference is between journalism as the servant of technology, and using technology tools in the service of journalism.

It’s what we’re seeing – what we’re all complaining about — even on the job front. When you’re interviewing for jobs, there’s so much attention on knowledge about technology.

It comes back to the importance of this first line of the creed. What happens to the journalist’s belief in the profession of journalism, but also the public’s belief in journalism?

What is it that would help you not wake up some morning and say, “Oh my god. I have no point?”

That’s a hard one.

Which happens in life. So, what is it about journalism that you’re trying to stay true to – that guides you no matter what the technology is, or what’s the challenge of the moment?

Engaging the reader as you’re forming a story. At the Maneater (the University of Missouri’s student newspaper), we’re going to post stuff about our editorial decisions. It’s another way of engaging our audience and adding to the transparency that’s been mentioned before.

We’ve heard a lot about “relevance” and being in touch with your audience. One of the touch points of the creed and most other journalism codes is “independence.” Where do those connect for people? How do you maintain a balance? How do those ideas co-exist in terms of a creed?

Independence from special interests. You have to be clear about that.

Back to what you were saying about authenticity, and how that’s currently reflected in the creed. The fourth line says, “I believe that a journalist should write only what he holds in his heart to be true.”

I think this statement should be more of a reflection of the profession, and not what the individual thinks is true.

What do you think the public would say about that question: “What’s the appropriate standard for truth?”

We are accountable for what we publish, what we photograph and what we print.

That’s a touch point:

As a journalist I’m accountable.

What else in the creed really stands out as important guidance for you?

“A journalist should only write what he holds in his heart to be true.” It would be hard for me, as a writer, to express anything that I didn’t really believe in.

You have to be careful with the balance issue though. As a journalist, if I believe something to be true, in my heart, I also have to acknowledge that I might be wrong. People are entitled to a viewpoint that I don’t necessarily hold to be true.

That’s part of what this statement tries to say. What’s your test of truth?

It can be a dangerous statement, if you interpret it incorrectly. What one person knows in their heart to be true is different than what another person knows to be true.

How would you go about creating checks and balances for yourself, in that regard?

That’s tough, because, to an extent, truth is not going to be subjective. I think some take that statement as a license to report things that fit their viewpoint.

Let’s stay with this for a while. After Walter Williams wrote this creed, many other codes of ethics followed. One idea begins most of these codes – the notion that journalism is about pursuing “truth.”

If you keep this statement in the creed, maybe you also should emphasize that it’s what you — the individual — believes to be true.

So, you have to test yourself.

There absolutely needs to be something in the creed about “full disclosure.” Additionally, if a journalist is personally vested in any way with the subject at hand, s/he must disclose this. That’s central to good journalism.

One of the statements in the creed addresses independence, which speaks to this. That’s probably the second point in most ethics codes. Independence is seen as a means to find the truth. Good point.

What else about truth telling? You’ll have gut checks about this throughout your career, in terms of holding yourself accountable, and being confidant that you’re not inserting your own opinions into a story. What do you think?

I think transparency is really critical now with the hyper-conglomeration of news agencies and media companies. It’s important for people to know who owns the news and who produces this news. Then they can ask the questions: Whom do I trust? Who’s not trustworthy? What are the potential conflicts of interest? I don’t see many news media offering this transparency — regarding ownership and agenda — to their audiences.

Is transparency in the creed? I don’t think it is.

I think the creed hints at it, but I don’t think it’s in there. The creed says, “I believe that the public journal is a public trust.”

That’s what the people I talk to who aren’t journalists are really worried about. Can they even trust the media nowadays?

That’s a big part of being a journalist — realizing that what you write is in the public’s best interest – not your own. You can say that, even though the news story might not reflect your opinion. But you can look at the story and say, “Okay, I’ve done my research. I have sources. This is what I can present to the public.” Then you can say, “As far as I know now, this is true.”

Do those who aren’t sure they can trust the media tell you why they’re not sure?

Often they don’t differentiate the opinion sections from the news. For instance, they read The New York Times and say, “Well, they have quite a few “liberal” — or whatever — columnists, so their news reporting must not be objective.

As journalists, we need to clearly delineate what is opinion and what is reporting.

From your conversations, do you know what it would take for people to trust the news media beyond making that distinction clear?

I think it’s about naming your sources. In my journalism class recently, we were discussing the issue of Sarah Palin and quoting anonymous sources. Every time we use an anonymous source, it tips the scale. We need five good, transparent sources to balance using one anonymous source. It’s about going after those sources. You know, not being lazy and saying, “This sounds good. I trust him, but he won’t reveal himself.”

What are the other reasons why people you know don’t necessarily trust the news media?

I think journalists often use the same sources. CNN will broadcast the same pundit every time for a certain issue. And if you don’t like him, you don’t trust CNN because you think they’re biased.

Let’s consider patriotism. How would you wrestle with that?

Since September 11, “patriotism” has gotten confused with “nationalism.” And there’s a big difference. Patriotism adheres to the idea of free speech, the right to have dissenting opinions. As a journalist, you not only need to cover dissenting opinions, but you need to hold those in power accountable. Patriotism might not be the best word to use anymore – something else less fraught with anxiety.

What if you surveyed the general public and asked whether the journalists should be patriotic. What would they say?

Yes.

So, we’ve got a yes.

But how many say no? And how many are unsure?

LAUGHTER.

This touches on one of the things I’m trying to do in my research – understanding how citizens and journalists define some of these terms differently. I think this is very important for journalists to understand. When we use a term, it may mean something different to the general public.

LAUGHTER

Say, you’re a reporter at The New York Times and you have a story. Here’s an example from this week. The Times reported there was a secret authorization to pursue Al Qaeda into Syria and other countries — this story originated with a leak from anonymous sources. I suspect that the government would have preferred that this information hadn’t been made public.

If you choose to rely on anonymous sources, what responsibility does that put on you, as a journalist? It’s a question of transparency. How do you help the public understand a decision like that?

I think the general public would see that as unpatriotic. But, it’s also what they expect from reporters. That’s why I think the public doesn’t expect journalists to be patriotic. They want objectivity.

So, you think the public would applaud the decision to publish a story like that.

Well, I don’t think they’d be happy about it…

So, maybe, they’re ambivalent. They wouldn’t be happy about it, but they would respect the decision. That’s interesting. I think this will be a real interesting scenario to wrestle with as we look at journalism’s future. Other thoughts?

The public’s definition of patriotism isn’t the same from citizen to citizen. In the last three presidential elections, the popular voter has been pretty much 50/50 — or very close to that. The definition of patriotism is divided among citizens too. We could define what it means to be “patriotic” in the creed. We’re being patriotic about democracy, the Constitution — not the administration.

Think about your own careers and the kind of journalist you want to be. What are your standards? What would you want to stand for? Not only that, what are the attributes you want people to know you’re striving to live up to?

I wrote “provoking thought.” I wouldn’t want a person to read a piece, and then they’re done with the issue once they finish the story.

Being a voice for the voiceless.

Sincerity, transparency and simplicity.

I put down respect for humanity and choice.

Being a part of the community. Readers see you as one of them.

Ongoing conversation. People comment on my stories.

Clarifying issues so the public can understand them. If you see journalists as public servants, then our mission includes ensuring the public has a better understanding of the world.

I wrote being available — responding — to the public. Otherwise, people don’t trust you.

“Relevancy” is a word we haven’t mentioned. That notion is inherent in wanting a connection to people. It’s a good word to have on the table.

Honest. Literate. Witty — with access.

So you’re in the know.

Being witty and having access is really important. I know this is kind of a bad example, but look at the amount of people watching Steven Colbert and John Stewart — taking the news and making it funny, more accessible. If the news is witty, then more people are going to want to know what’s news.

Approachable. I don’t want to be someone in an office who tells you what’s happening in your world. I want to be part of the community.

In this case, I wrote “authentic” — like Dr. Seuss says, “I mean what I say and I say what I mean.” People would see that and value it.

This wide range of ideas is fascinating. But there are some themes. Let’s try answering this question from the perspective of the public. What would your friends who aren’t journalists say that we didn’t mention?

Information you can use. “What time is the show? What am I going to do this weekend?”

Usefulness, that’s it.

Immediacy is important.

One of the reasons I became interested in this research was the question: “Who is a journalist?” And

if you have something like this creed, and you really sought to live up to these principles in your career, then you could call yourself a journalist.

It’s the pursuit of working within some guidelines.

If you’re not a professional journalist — a citizen, a “blogger,” etc. — but you’re really striving to do the things we’ve talked about, then that’s enough, as far as I’m concerned.

But if you’re not honest with yourself about trying to live up to these standards, then there’s no reason to use the word “journalist.”

When I first read the creed, I was looking at journalism schools. This very romantic idea excited me. It’s a creed — it’s everything that journalism represents. This is what we stand for.

Comments