The Metropolitan Transit Agency prepares to distribute N95 masks to employees in early 2020. Courtesy of MTA via Flickr

Breaking down myths of progressing “post-pandemic:” Careful COVID-19 reporting is still crucial

Here’s how to debunk common perceptions of the virus, where to find data, and why it remains an important equity issue

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Reynolds Journalism Institute or the University of Missouri.

President Joe Biden officially declared the end of the COVID-19 public and national emergency in spring 2023. Four years after that emergency was declared, just 20% of Americans view COVID-19 as a major threat to the health of the U.S. population.

Mainstream media has largely closed the chapter on COVID-19 reporting. Reporters shifted away from providing updates about COVID-19 levels in their area. Newsrooms sunsetted their pop-up COVID-19 newsletters. Phrases like “post-pandemic”, “during the pandemic” and “height of the pandemic” are resplendent among hard news, news features and commentary alike, bookending an amorphous, strange, eviscerating period of time of grief, loss, and distance mediated by masked faces and Zoom meetings.

But the thing about viruses is that declaring them over doesn’t make them disappear.

When Biden announced his withdrawal from the presidential race this summer, he did so in the wake of an active COVID-19 infection.

Journalists may want to be done with COVID-19, but the virus isn’t done with us — or the communities we live in and report on. It is a disservice to people’s health and lives to mischaracterize or inaccurately report on COVID-19.

COVID-19 is still here. And it remains disabling and deadly. That’s why other journalists and I presented on the importance of better COVID-19 reporting as part of IRE’s virtual-by-design conference, AccessFest.

At least 400 million people globally are living with Long COVID — which can manifest as over 200 different symptoms, ranging in severity from mildly impacting quality of life to completely debilitating.

“Anybody who is reading any of our publications, any of the freelance work we’re putting out, are probably people who have experience with Long COVID themselves, are taking [COVID] precautions, are caretakers for people with Long COVID,” said The Newsette’s editorial director, Reina Sultan during the panel. Sultan, who lives with Long COVID, added “It’s really important that people who read what we write can see themselves in these stories.”

Journalists may want to be done with COVID-19, but the virus isn’t done with us — or the communities we live in and report on. It is a disservice to people’s health and lives to mischaracterize or inaccurately report on COVID-19.

“I think the main message from most people in positions of power has been, ‘It’s over, we’re fine,’” science journalist and author Ed Yong said. “But I think that’s a lie. And we are meant as a profession to expose lies. So, you know, if that feels like something you want to do, there are lots of ways of getting started.”

COVID-19 reporting requires care and context

Accurate COVID-19 reporting, Mother Jones disability reporter Julia Métraux says, means “bare minimum, setting it at present tense.”

That means nixing the phrases “during the pandemic”, “post-pandemic,” or “height of the pandemic” in your reporting, news broadcasts, headlines and other content. .

Instead, Sultan said, write with specificity about the specific time period, year, or dominant SARS-CoV-2 variant (e.g. Delta, Omicron, etc.) being referenced.

Beyond that, it means recognizing that while the scale of mass disablement and debility with Long COVID is novel, gaslighting, ignorance, and denial of chronic illnesses — many of which, like Long COVID, do not have a cure — is historically not new.

Misogyny plays a role: people with ME and autoimmune disorders are disproportionately women, and those diseases have largely gone understudied and undercovered, leaving both the media and public health infrastructure woefully under equipped to address Long COVID — which looks to follow a similar gender-based pattern.

“Some reporters go in with a framework of, ‘Oh, look at this thing where it’s debatable how much it’s impacting people. Well, you wouldn’t think it’s debatable if you’re looking at how people have been struggling with chronic illnesses for a long time,’” she said. “As a health reporter and a similar lived experience with autoimmune disorder, I think in order to do better reporting on Long COVID … [it means] showing this history, as well,” she said.”

One great resource is from Fi Lowenstein, an independent journalist with Long COVID, who authored a guide to better coverage of the illness.

When we spoke, Yong echoed much of what the guide laid out: Namely, that better COVID-19 coverage means going beyond just interviewing people with Long COVID and treating them as “anecdotal fodder.” Because they’re experts on their own lives, conditions, and people with their own agency.

“If you are writing about this, and you have not realized that … long-haulers are the world’s greatest experts on Long COVID, then you’ve done something wrong,” he said. “I would find and talk to long-haulers and really try and understand what their lives are and how they are forced to navigate the world with as much sensitivity and accommodation as is necessary.”

Phoebe Petrovic, an investigative reporter at Wisconsin Watch who also serves as a caretaker for her partner with Long COVID, said that now is more crucial than ever to accurately report on the ongoing impacts of COVID.

“We as journalists, who hold power to account, who are supposed to follow the facts where they lead … and to share important information to the public to inform how they go about their daily lives or how we embark on structural changes — we have a really important role to play in making sure the ongoing COVID crisis is covered properly,” she said.

Part of that means dismantling common misconceptions circulating from earlier in the pandemic that are still repeated in stories. Among them:

- Misconception: “We have to build immunity because we lost it during mask mandates.”

Fact: COVID-19 infection causes immune dysregulation, both in severe and mild acute infection.

- Misconception: “Only vulnerable and high-risk people are still likely to develop worse outcomes after a COVID infection.”

Fact: The list of risk factors for adverse outcomes post-COVID infection is extensive, and each COVID-19 infection impacts your immune system, so it’s akin to playing Russian roulette with your health — regardless of how good it is.

- Misconception: “Long COVID can last for weeks or months.”

Fact: The trajectories of recovery of people living with Long COVID vary wildly and there is no cure for Long COVID — like other chronic illnesses.

- Misconception: “COVID is like the flu” or is part of “respiratory virus season.”

Fact: This disease impacts every organ system and causes severe disease and disability, along with increased risk of cardiac events, more frequently than the flu, RSV, common colds, etc.

Yong has written about Long COVID denial, and deep dives into the nuances of fatigue and brain fog, two of the most common Long COVID symptoms. He says it’s crucial to provide subtlety and granularity to descriptions about the illness, instead of decontextualized bullet points.

“They sound like the kinds of things that everyone goes through … but the reality is so completely different to what a healthy, abled person could ever imagine that it just sounds unbelievable,” he said. “I just don’t think most people can truly understand that a body can be so depleted of energy that you simply cannot go about your past everyday life. If you don’t see that yourself, then really the only outlet is to read the testaments of other people or to read pieces about this, and I think that’s why it’s so important to tell those stories.”

But proceed with time, care, humility and compassion when covering Long COVID, he emphasized: “We’ve had a lot of bad long COVID stories from people who are sort of barreling in from a position of hubris and arrogance. We need more stories that come from a position of empathy and care.”

Some helpful places to start reading more about COVID and expanding your sourcing

- The Sick Times (Disclaimer: Yong is on the advisory board and I am the publication’s podcast producer.)

- Long COVID Connection

- Long COVID source list for journalists

- The People’s CDC

- COVID Action Map (Links out to grassroots groups acting around COVID, including clean air organizations and mask blocs)

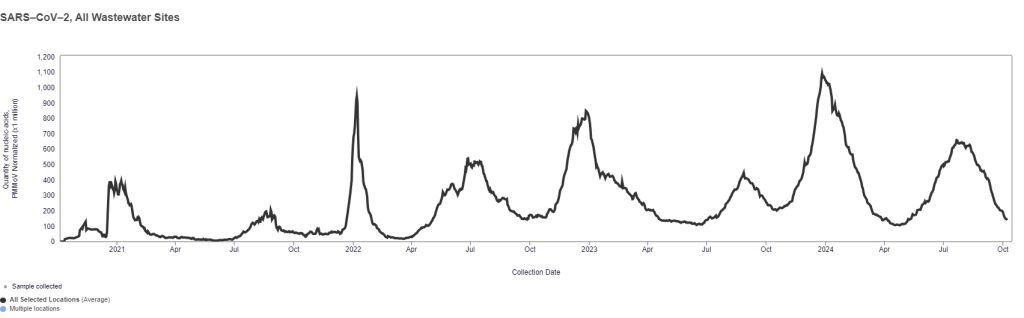

Data-driven COVID-19 reporting is still possible — with caveats

While the data landscape around the virus has shrunk, there are still key numbers that show reporters at least some of the picture: namely, wastewater surveillance (or the tracking of diseases and other health threats through waste), hospitalization data, and deaths.

And more data is coming soon — numerous types of hospitals will once again be required to report the number of hospitalized patients and new admissions with lab-confirmed COVID-19 starting Nov. 1.

COVID-19 data sources

- WastewaterSCAN Dashboard

- Biobot Analytics: Respiratory risk reports

- Centers for Disease Control: COVID-19 Wastewater Data and CDC COVID Data Tracker

- List of state and some local wastewater dashboards

It’s important to note that wastewater is a proxy, community-level measurement — since case tracking is no longer as accurate with more people using at-home COVID-19 tests, it’s difficult to draw conclusions about specific case numbers by looking solely at wastewater data.

Health and data journalist Betsy Ladyzhets, who co-founded The Sick Times to cover the ongoing Long COVID crisis, cautioned that death certificate numbers are likely to be undercounts — and a complete picture of COVID-19’s impact means looking beyond death tolls.

“Our system for tracking deaths in the United States, and this is also true in other countries, is very imperfect and has a lot of room for error,” she said. “Also, Long COVID can be really disabling and can really mess up people’s lives. So [there’s] a lot, a lot, a lot to track there in terms of the continued impacts of COVID still spreading.”

And while the CDC has been venerated as the expert on public health, during the AccessFest panel, Ladyzhets also encouraged reporters to take CDC data and perspectives with a grain of salt, because the national public health agency also has other vested interests.

She cited corporate pressures in the middle of the omicron wave in 2021, including a letter from the CEO of Delta Airlines, pushing the CDC to reduce its isolation guidelines from 10 to 5 days — ”not based on legitimate science on how COVID works or how long the virus stays infectious.”

Now, as of this September, the CDC’s new guidance is a one-day isolation.

“Think about when you last had COVID or a cold or any kind of illness,” she said. “Did you feel better within 24 hours? Probably not.”

Part of better COVID-19 reporting is retaining access — in reporting process and spaces

Between the push for return-to-office, the growing apathy toward the lack of masking requirements and efforts to clean the air (COVID is airborne!), and the rise of mask bans across the U.S., public spaces are increasingly less safe for me and other disabled people, even with masking indoors and outdoors.

In the U.S., young, working-age people of color have the highest rates of COVID infection — potentially setting them up for increased risk of Long COVID with reinfection. And many may not know if they are ‘high-risk’ themselves.

“That’s actually what happened to me,” Sultan shared during the panel. “After I had one COVID infection, I developed a slew of other conditions that left me disabled, and I was not aware that I had risk factors that would contribute to that … We all have things in our health that we are not aware of or might contribute to being at-risk. That’s not just for us, it’s for every person we interact with.”

I’ve been gutted to see the growing apathy and indifference reporters who otherwise care about accurately, thoughtfully, and rigorously covering marginalized communities have toward disabled people impacted by a virus that has pushed many out of society and deepened societal fissures.

Yong agreed, “If you have read all of this and are surprised, if you thought that the pandemic was over, and if you don’t know personally people who are still struggling with the long-term consequences of COVID, then what it means is your circles do not include the very people who you are meant to serve through your work.”

Tips for increasing accessibility in the reporting process and journalism spaces

- When interviewing people with Long COVID, factor in time and flexibility.

- This may also mean doing interviews via email or text or sending questions in advance to allow people to prepare, and adding as much transparency into your reporting process as possible.

- Wear a mask when interviewing sources (at the very least!).

- “I … don’t think we should make people we interact with materially worse,” Petrovic said during the AccessFest panel. “I think a lot about us journalists who are interfacing with or talking with sources who are in more precarious situations who might not have the time to research or be aware of the risks on COVID, but for whom one COVID infection could really mean the difference between them keeping their jobs or being out on the streets.”

- Invest in remote options that aren’t afterthoughts — and, in-person, create a culture of masking and testing.

- Many journalism organizations and conferences reverted back to in-person events as early as late 2021. Given how unsafe travel remains with regard to COVID-19 risk, this is inherently inaccessible to many journalists and forces them, again, to choose between livelihood and safety. While some venues can no longer enforce masking requirements, conference organizers would do well to encourage masking as a science-backed intervention that helps attendees keep each other and themselves safer — and invest in remote options like AccessFest to provide people a way to continue to participate in professional life and expand broader access to people who otherwise would not be able to take part in programming. Both these options broaden the range of people who can participate in journalism professional development.

- Clean the air.

- Because COVID-19 is airborne, ventilation, such as opening windows or investing in HEPA air purifiers can help reduce the amount of virus in the air.

If newsrooms want to maintain and still strive for the progress espoused by leaders in 2020, creating accessibility through remote options, masking requirements, and cleaning the air — and accurately chronicling the reality of COVID-19 — are crucial components to furthering a more equitable industry.

Cite this article

Salanga, James (2024, Nov. 12). Breaking down myths of progressing “post-pandemic:” Careful COVID-19 reporting is still crucial. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/breaking-down-myths-of-progressing-post-pandemic-careful-covid-19-reporting-is-still-crucial/