Photo: Nick Hagen

VERDAD is tackling the blind spot in the fight against radio disinformation

Radio remains one of the most trusted and accessible sources of information for immigrant communities in the U.S., especially among Latino listeners, where local hosts become an integral part of daily life. But its affordability, accessibility, and the wide reach of live broadcasts also make it a powerful vehicle for spreading misinformation, which is often repeated and rarely recorded, making it difficult to fact-check after it airs.

“Latinos use radio to listen to music, news, and entertainment, and then a radio show comes on that slowly builds your loyalty, something I think is harder to achieve with a newspaper,” said Tamoa Calzadilla, Editor-in-Chief of Factchequado-Miami. “I believe the Uber driver going from your house to the airport, listening to the radio the whole way, is not picking up a newspaper.”

Calzadilla says radio not only outpaces newspapers in reach, but it also fosters a deeper emotional connection. “It’s the difference between active and passive consumption. When you consume books or newspapers, you have to read, interpret, and actively engage to understand what you are reading,” she explained. “With radio, it’s passive consumption. You’re taking a shower and listening to someone talk. You don’t have to do anything at all.”

That passive consumption, combined with trusted voices and minimal oversight, makes ethnic radio a potent space for misinformation, whether locally generated or strategically planted by foreign actors like Russia, China, or Iran. Many of these programs operate as echo chambers, with little to no dissenting viewpoints, which compounds the challenge of monitoring and countering false narratives.

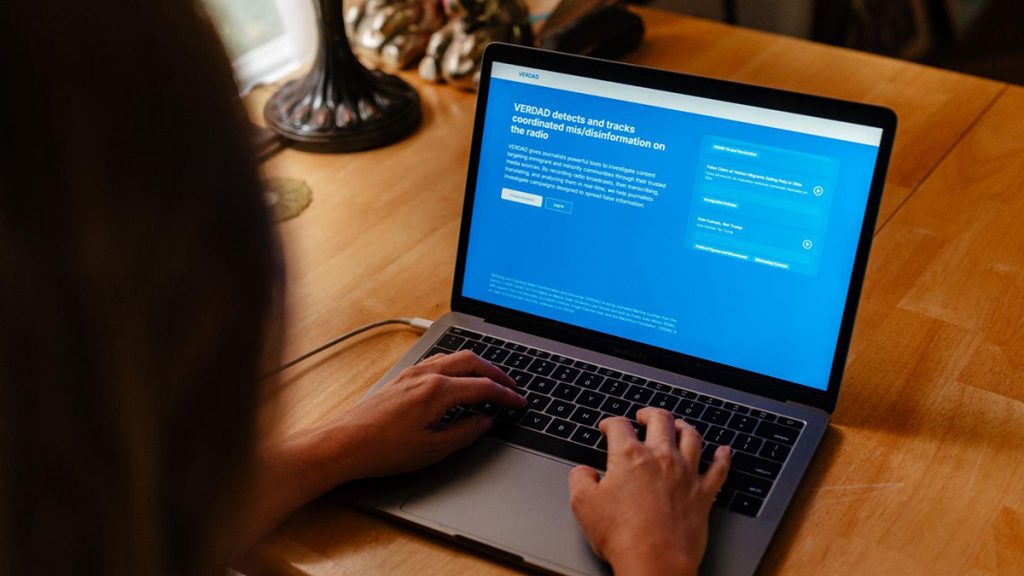

To address these growing concerns, we developed, with RJI’s support, VERDAD. It is a free, open-source tool designed to monitor radio broadcasts and help identify and counter disinformation.

VERDAD monitors so reporters can focus on fact-checking

Before VERDAD, the only way to monitor Spanish-language radio for misinformation was to literally listen to it 24/7. That’s what researcher Stephanie Rodriguez did. In 2023, while reporting for Feet In Two Worlds (FI2W), she spent nine months listening to Spanish-language radio stations across the United States. She monitored known disinformation sources and tracked the rise of new voices spreading falsehoods.

There are roughly 62.5 million Latinos residing in the United States, a significant part of the U.S. population. Rodriguez knows their voices are underrepresented and misrepresented in mainstream media, resulting in missed opportunities for critical and accurate reporting.

She monitored Americano Media, a now-defunct Spanish-language radio network often described as the Spanish equivalent of Fox News, and the show Cada Tarde, a radio station in Miami. It’s where host Carines Moncada told listeners that immunity to COVID is stronger after the body has fought the illness rather than after receiving two vaccines. Moncada claimed that COVID came from a lab and its development was financed by Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Rodriguez’s research examined the rumors, conspiracy theories, and propaganda that have infiltrated Spanish-language broadcasts. But the nonstop listening began to take a toll. She said that the challenge of listening was that simply hearing the content wasn’t enough.

“Capturing evidence of misinformation was really difficult. I had to record in some way, and I would have to hold my phone to the computer, or I would have to try and write it down really quickly, or try to transcribe as they were talking,” Rodriguez said.

Trying to track a broadcast without a recording, then verify that it occurred, became nearly impossible due to the fleeting nature of radio.

“You can’t just go back and replay what you heard,” Rodriguez added. “With radio, it airs once, and then it’s gone. That made it really frustrating, especially when you’re hearing people say all kinds of things that feel intentionally misleading or harmful.”

VERDAD makes this hard work easier by automatically recording Spanish-language radio broadcasts, transcribing and translating them into English, making radio monitoring more accessible and actionable for journalists.

Keeping up with the information war

Journalists and their shrinking newsrooms are massively outpaced by misinformation. It requires a significant amount of time and manpower to sift through the constant barrage of falsehoods.

“The first issue is the speed at which disinformation moves,” said Desirée Yépez, an award-winning journalist and managing producer at Radio Bilingüe. “The second is that disinformation has become more refined in both form and content. Narratives are tailored to different social groups in which disinformation circulates.”

Most journalists still rely on fact-checking after the disinformation has already begun to spread, and Yépez notes that fact-checking still adheres to journalistic standards that require a significant amount of time and effort.

“Verifying something isn’t an immediate process. So if a piece of disinformation goes viral, like when people were saying that people eat pets during an election cycle, producing content to confirm whether that’s true or false takes time,” Yépez said. “It can take days or at least 24 hours, as the process involves reporting and gathering sources. It simply doesn’t move at the same speed.”

So when it comes to Yépez’s work, VERDAD speeds up her process by surfacing the disinformation more quickly.

“VERDAD is disruptive,” Yépez said. She used VERDAD to identify story leads by searching for keywords tied to sexual and reproductive rights, gender, and LGBTQ topics.

“A tool where you can say, ‘OK, I’ll go here and find a whole cluster of disinformation’? That didn’t really exist before [VERDAD],” Yépez said.

Helping resource-strapped community news outlets

El Central is a bilingual community newspaper in Detroit that has been in operation for 37 years. It recently created an online platform in hopes of reaching a younger audience, but like so many local outlets, it operates on a shoestring budget. With no full-time reporters and limited resources, it simply doesn’t have the capacity to track or counter disinformation that affects the very community it was built to serve.

In the run-up to the 2024 U.S. election, the paper witnessed a surge of misinformation and disinformation tied to the presidential campaign. As this misinformation infiltrated the community, El Central had no easy means to address it or counter the false narratives.

Detroit journalist Estefanía Arellano remembers with frustration the incorrect claims that circulated in her community. She writes for El Central and was trained by the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) to identify disinformation.

“It was a political year, and there was a lot of stuff circulating that was blatantly false,” she said. “Latinos believed the falsehood that Kamala Harris was a socialist.”

Many Latinos, particularly those from countries like Cuba, Venezuela, or Nicaragua, have experienced firsthand the negative impacts of socialist and communist parties turned authoritarian regimes, and have a strong reaction to the word.

El Central didn’t have the capacity to keep up with the disinformation. Arellano believes disinformation influenced the Latino community’s voting patterns. “It altered what they thought about each political candidate,” she said.

It wasn’t just in Michigan; after Kamala Harris became the Democratic nominee for president, disinformation about her being a socialist or communist circulated widely in Latino communities nationwide.

Calzadilla, the Editor-in-Chief of Factchequado-Miami and the former director of elDetector, the fact-checking platform for Univision Noticias, collaborates with media organizations and universities to combat disinformation that primarily affects the Latino community.

Calzadilla recently spoke at Stanford University, where she presented VERDAD and shared examples of the misinformation about Vice President Harris that was circulating on Spanish-language radio shows.

“I showed them a screenshot from VERDAD that said ‘Kamala Harris is a communist,’” Calzadilla said. “These are the kinds of narratives VERDAD identifies, and makes it easier because you’re not just hearing it, you can also see it with the transcript, and you can analyze it.”

“I told them that before VERDAD existed, we didn’t have a way to monitor radio efficiently,” Calzadilla said.

VERDAD gives David a leg up against Goliath

Following the January 6, 2021, insurrection, Spanish-language radio, particularly in Florida, increased as a platform for disseminating disinformation, spreading false narratives about who won the election and what happened at the U.S. Capitol that day.

The false narratives in Florida about the insurrection led a coalition of organizations in Miami to analyze content from four Spanish-language radio news shows. They found that hosts and callers were spreading false narratives about election fraud and other conspiracy theories that mirrored those propagated by Russian state media.

China, Iran, and especially Russia are aggressive and sophisticated when it comes to disinformation targeting the United States, aiming deliberately to undermine trust in U.S. institutions, fuel division, and influence elections. One of its most effective strategies has been the use of troll farms like the Internet Research Agency, which created fake accounts posing as Americans to push divisive content about race, immigration, and politics.

When people trust institutions, like the courts, the media, and electoral systems, they are more likely to accept outcomes of elections or public policies even when they disagree with them. Trust gives democratic decisions legitimacy.

Sarah Alvarez, the founder of Outlier Media, notes that the erosion of trust extends to critical institutions, such as the scientific community and public health agencies, which weakens public responses to threats like climate change and public health crises.

The consequences of disinformation aren’t abstract; they directly affect individual behavior, community cohesion, and society’s ability to solve complex problems.

“People who didn’t want to believe COVID was real didn’t wear masks, and they died. That’s the serious individual effect of disinformation,” Alvarez said. “We weren’t trying to convince people to get the vaccine, we were trying to help them stay safe, starting from what they believed.”

Alvarez says Americans are losing their ability to process unwelcome but necessary truths.

“There’s a real emotional incentive to believe climate change isn’t as serious as it is. It’s easier to dismiss it than reckon with the behavior change it requires,” she said. “If we keep hearing that air quality alerts don’t matter, we might just leave our windows open all day, and that’s actually dangerous.”

This disconnect, Alvarez argues, erodes our collective ability to solve problems, weakens public health responses, and fuels fear and isolation. That’s why, she says, newsrooms must treat disinformation monitoring as a core part of their reporting, not just something activated during a crisis or an election.

“It shouldn’t be reactive; it should be routine,” Alvarez said. Tools like VERDAD, which she used leading up to the 2024 election, are helping fill that gap by flagging harmful narratives before they spread.

“VERDAD really should be part of the newsroom’s daily workflow, not just something you use when something is blowing up,” she said. “It helped us make sure we weren’t missing anything. It became a way to monitor, not just react, so we could serve our community better.”

Cite this article

Guzmán, Martina (2025, July 31). VERDAD is tackling the blind spot in the fight against radio disinformation. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/verdad-is-tackling-the-blind-spot-in-the-fight-against-radio-disinformation/