A pop-up newsroom goes digging on Facebook to share its COVID-19 news

When COVID-19 first hit, the Missouri School of Journalism quickly realized local newsrooms everywhere would be struggling to keep up with news about the virus. So the school created a “pop-up” newsroom called the Missouri Information Corps. We spent the summer reporting issues related to the pandemic and distributing stories and information to news outlets for free.

We also found new audiences.

The newsroom was split into two teams: reporting and distribution. The reporting team produced plenty of traditional reporting. It broke stories several times, including news of outbreaks in the state’s prisons and the slow response by counties with CARES Act funds. Many of the stories were picked up by newspapers and localized.

Team distribution — Regan Huston, Taylor Guidry and Arin Jemerson, led by editor Madison Conte — experimented with less traditional ways to reach audiences on social media. As avid social media users, (Gen. Z-ers, hello!) the distribution team wanted to develop a plan to tackle the spread of that other virus — misinformation – online.

We decided to narrow our efforts to Facebook. Ultimately, we found that there’s a lot of reason for hope in the news media industry, and there’s one surprising obstacle that we hope Facebook fixes.

What we did: The process

As digital strategists, we’ve noticed an increase in the use of infographics and visual explainers on social media. These graphics are visually pleasing, easy to consume, and ready to share across all platforms. We wanted to experiment with this on Facebook. But, as a small startup, we didn’t have a following that would lead to impressive engagement on any of our posts.

We knew we had to meet people where they were. The easiest way for us to do that was to utilize community Facebook groups.

We knew the groups existed; we just had to find them. This was the least fun part of the job because it’s tedious but important scutwork. Newsrooms have always done this kind of granular research, but for stories, not to find audiences.

We made a list of every county in Missouri and then searched keywords related to that county on Facebook to find associated pages. Before we started posting information in the groups, we made sure to introduce ourselves. We wanted to create a relationship with the community and build trust.

What surprised us

We were expecting and preparing for pushback but were pleasantly surprised by the amount of positive engagement we received. For example, our “Why Should I Wear a Mask?” infographic reached more than 5,200 Facebook users. In another post, we included a video interview with a local health department that explained why COVID information is ever-changing, and that reached more than 4,100 Facebook users.

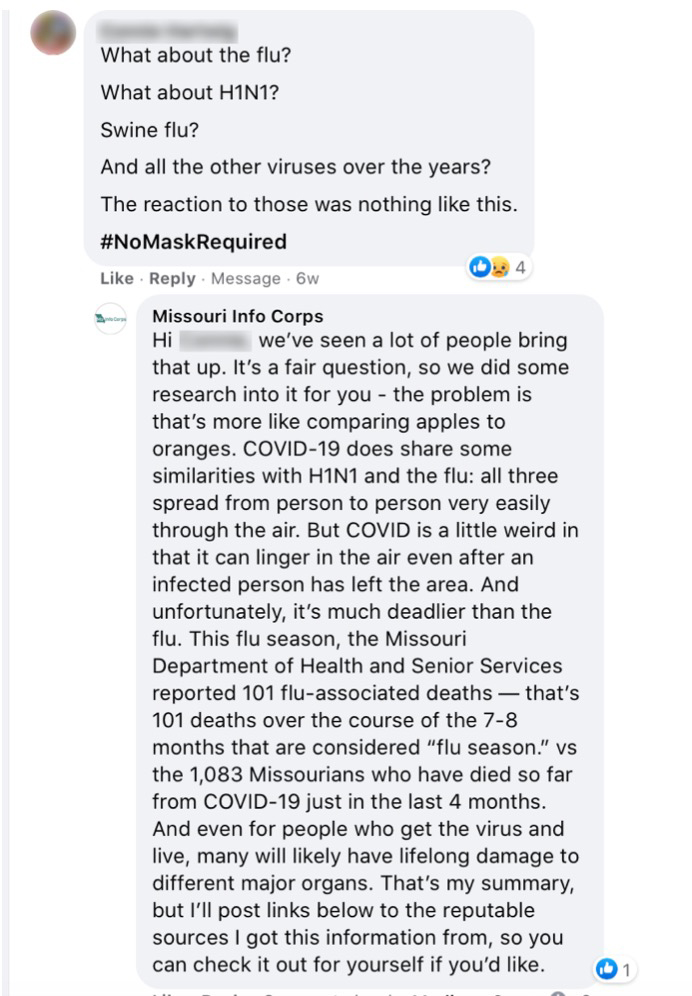

We also decided to take our strategy one step further by responding to comments on our posts. Some users asked for tips, such as the most effective type of mask to wear. We also ran into a few skeptics.

Our primary focus was sharing information, but we also wanted to be conscious of any misinformation left as comments on our posts and do our part in stopping the spread of it. To do this, we’d carefully research the false claim and respond in a friendly and informative manner while linking to trustworthy sources.

Rather than arguing with skeptics, we wanted to inform other readers of the most accurate information available. Below is one example of how we responded to a skeptical Facebook user on our “Why Should I Wear a Mask?” infographic. We were careful to be respectful and acknowledge why the question was valid, and then followed up with several links to trustworthy articles and studies to further prove our point.

Facebook errors: The takeaways

Several times while posting in local groups we ended up in what we dubbed “Facebook Jail.” After posting a duplicated copy of our infographics to a handful of groups, we received the following message: “Your Request Couldn’t Be Processed: There was a problem with this request. We’re working on getting it fixed as soon as we can.”

While we still have no clear answer for why this happened, based on a little research and similar experiences from others, we concluded that this was Facebook’s response to us posting similar messages repeatedly in groups. Maybe it was flagged as COVID-19 spam instead of dissemination of trustworthy COVID-related news. Regardless, this is an exhausting and frustrating wall to hit when you are working hard to spread reliable and accurate information to communities at-risk for mis- and disinformation. Social media platforms have become the new means for delivering news and it seems ironic that those of us trying to deliver legitimate news are running into obstacles that hinder us from doing so (while fake news posts about inhaling steam as a COVID recovery aid are allowed to go viral).

Our recommendations

Our experience suggests that there are audiences interested in engaging with journalists via social media if you are transparent in your goals, respond politely and include the community along the way.

Traditional journalism is still important, but it’s also important to adjust and experiment with other means of distribution as the industry continues to rely on social media. Oftentimes, we think social media is only effective for reaching the younger generations. But on Facebook, we were able to build a relationship with older audiences from rural communities and provide important information in an accessible way, all in a short period of time.

As the power of social media grows, we as journalists are losing control over the means of distribution. It’s important that we learn how to meet people where they are.

Regan Huston graduated magna cum laude from the Missouri School of Journalism in 2020 and is now working at VICE as an associate video strategist.

Arin Jemerson is a 2020 graduate of the Missouri School of Journalism with a convergence investigative reporting emphasis. She is now a social media manager for the New York Amsterdam News as part of the Instagram Local News Fellowship program.