Talk Story, Write Story helps financially disadvantaged children write their way into college

Talk Story, Write Story is a two-verb, one-noun description of all human communication. Talk came first, writing followed, turning all of us into storytellers regardless of the delivery system.

Talk Story, Write Story is also my writing program, which didn’t have a label for its first five years. I started calling it that as a shorthand explanation of what I was doing with Native Hawaiian kids whose aboriginal culture is grounded in oral stories passed down from generation to generation. White missionaries created a written Hawaiian language in the 1830s, so conversations with these students, as well as Native Alaskans with a similar history, are usually in straightforward subject-verb-object narratives. In other words, perfect declarative sentences.

Talk Story, Write Story describes cost-free, one-on-one writing workshops that organically evolved to help financially disadvantaged high school students showcase their heritage, personalities, skills and goals through personal essays. The program started nearly 20 years ago when an English teacher in my 80-percent Native Hawaiian community on Maui asked me to help a young man with his junior class essay. If he didn’t complete the assignment he was in danger of flunking the class. Reluctantly, he sat with me on a bench under a vast Monkeypod tree outside his classroom, talking through the story he wanted to tell, then writing it on a yellow legal pad. He passed the class, I submitted his story to a writing competition, and he won first prize.

More students asked for help. Some wanted to go to college. Because 70 percent of the kids at our school qualify for free lunch, and many for free breakfast, the best way those talented, smart kids could achieve higher education was through scholarships. Talk Story, Write Story gave them a better chance to go to college and earn money to pay for it by writing their way in.

Years passed, my hair turned white and my thumbs developed tendonitis from typing. But the kids, and parents on their behalf, kept coming: more than 200 in my hometown, then nearly 50 in Alaska when I was asked to take the program there. Kids of Native Hawaiian, Native Alaskan, Hispanic, Caucasian and Asian heritage worked tirelessly through Talk Story, Write Story earning nearly $6 million in college scholarship awards, including 15 Gates Millennium Scholarships and three scholarship finalists (www.gmsp.org).

This academic year I will use my fellowship with the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute to partner with the Columbia (Mo.) Daily Tribune to create a template to introduce Talk Story, Write Story into more communities via sponsoring local newspapers. Through RJI’s and the Tribune’s sponsorship, I hope to recruit and train enough volunteer mentors to work one-on-one with the financially disadvantaged local high school seniors who qualify for the program. Together, our goal is to provide the opportunity and support these worthy students need to talk and then write their way into higher education.

Talk story, write story, sibling success story

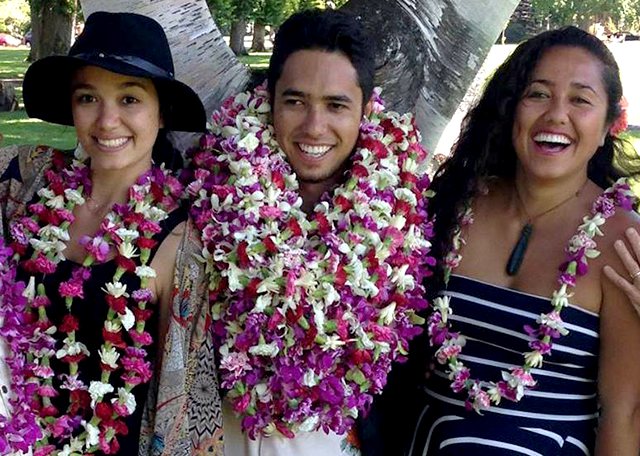

Three siblings from Hana, Hawaii — coached and mentored by Tad Bartimus — are Gates Millennium Scholars. See the photo at the top of this story.

Hau’oli Kahaleuahi, left, is a senior at Seattle University majoring in strategic communications with a specialty in marine conservation. Her brother, Joseph “Tevi” Kahaleuahi, graduated in May with a degree in natural resources biodiversity and forest ecosystems from Oregon State University. He plans to pursue a master’s degree in the forestry field. Their sister, Lipoa Kahaleuahi, right, earned a Bachelor of Arts in Global Studies from the University of California at Santa Barbara, and a master’s in teaching from Chaminade University in Honolulu. While at Chaminade, she was a teacher in the Teach for American program on the Big Island of Hawaii.

How they spent their summer: Hau’oli was an intern at the Marine Conservation Institute in Seattle, Tevi interned to be a master arborist in Oregon forests, and Lipoa worked with young Māori students in New Zealand.

The Gates scholarship program provides recipients with up to 10 years of funds to pursue their education.