Marisol Seda at the Women March 2020. Photo: Diosa Pacheco

Gender and age discrimination play a key role in female Hispanic journalists staying at the bottom

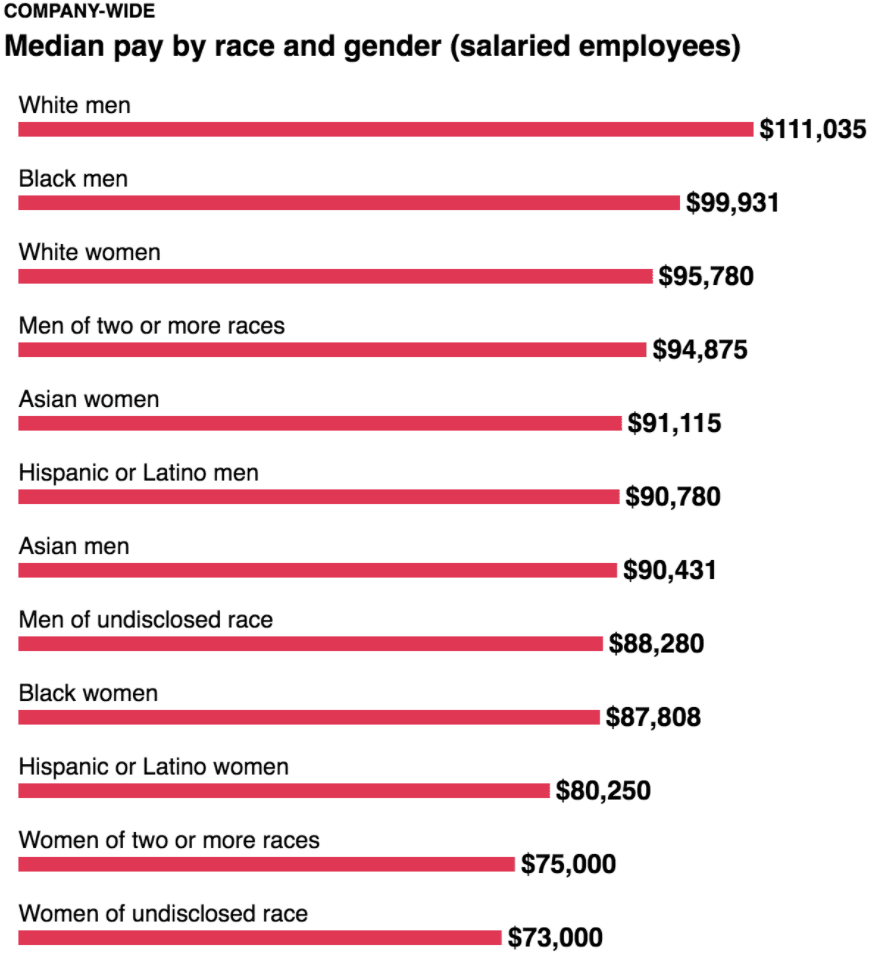

Our recent Fundamedios study revealed that salary disparities are the main type of discrimination against Latino journalists, and the situation is worst regarding Latinas. The gender gap is a problem worldwide, but Latina, or Hispanic, female journalists are at the bottom of the ladder.

Additionally, they have less opportunities to grow and, opposed to men, women tend to be seen as having an “expiration date” becoming less likely to be promoted or hired after a certain age. Stereotypes set the industry, and Latinas need to fit into a preconceived mold to keep their jobs and to grow. Gender and age are therefore huge discrimination factors adding to the ethnicity component.

It doesn’t matter that the Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII) theoretically prevents discriminating against someone on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or gender. It doesn’t matter that The Equal Pay Act of 1963 (EPA) makes it illegal to pay different wages to men and women if they perform equal work in the same workplace. It doesn’t matter that The Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA) protects people who are 40 or older from discrimination because of age. In practice, based on our survey responses and other interviews, all of the above legal framework is overlooked and disregarded by employers. And, of course, The Pregnancy Discrimination Act isn’t often respected either.

According to an AAUW study published in 2019, Latinas make 55 cents versus $1 that a white male makes for the same job. In the news sector, the wage difference may not always be that large, but we have found multiple cases that confirm it does exist.

Although the media shines light on almost everything, the payment structure in newsrooms is a black hole and very few media outlets have published transparent information about it or encourage their employees to share their salaries.

The Los Angeles Times Guild acknowledged a 30% payment gap for Latino women. The Washington Post Guild recognizes that its gap could even be 35%.

The payment gap could be worse in other places. Celimar Adames Casadeluc, who has worked for over 20 years in WAPA-TV in Puerto Rico, was astonished when she discovered the truth. “It’s shocking to find out after a lifetime in a company, that I considered my home, where I grew up for so long, and I would assume that they’re going to make me feel at home. You assume that your work will really pay off, and that you are by everyone’s standards, but there is secrecy about the wages. One day you found out the truth, I was paid 45% less than a younger male journalist with less experience and less responsibilities in the newsroom.” she said.

Celimar was the leading anchor of the evening newscast for 18 years. She was the fifth co-anchor with the legendary Jose Guillermo Torres, who holds the Guinness Record for the longest time hosting the same news service after retiring after 43 years and 10 months.

This is the best example of what nine women journalists in New York said: “Men get older with gravity, while women expire”. It is a kind of normalized standard on TV that men show their gray temple, while women need to show smooth skin and young bodies. Blunt discrimination is what increases ratings.

NY1, a 24 hours local news channel from Charter Communications, is facing four demands for sexism and ageism. Among the nine plaintiffs, four are Latinas.

The first Latina who dared to challenge the station was Marisol Seda, a four-time Emmy awards recipient. She had top assignments, breaking news, as well as coverage where she needed her experienced skillset to improvise and succeed. Despite her qualifications and excelling in her work, Marisol says she was denied the opportunity to grow within the company’s organizational chart

“Marisol was given the most important stories and difficult tasks, because she could do it. But for Marisol when it came the time to invest in her, make her the full-time anchor or newscaster, she wasn’t considered because she didn’t fill the mold”, says Brian Heller, Seda´s attorney.

The mold in this case translates to younger journalists, and definitely not women over 40. Marisol was the first who sued the company. After her, eight additional women followed with similar demands.

Marisol Seda experienced discrimination due to her age and gender in an English language station. But she knows this could be even worse in Hispanic media.

“There is a mold of what a Latina reporter should be. We are much more than a guitar body and a stereotype of how we must dress, sit and walk. Women journalists should not be vedettes.” she said.

Employers in some stations demand that the female news anchors look voluptuous, wear close-fitting clothing and, of course, miniskirts. There are places where bosses even tell their anchors what kind of bra they should wear. This is outlined in a lawsuit against Telemundo NBC Universal.

Male and female Latino journalists also do additional work they are not compensated for, such as translating pieces produced in English language into Spanish when an outlet decides to provide information in both languages.

Jennifer Marcial, who is the Spanish Senior Content Editor at the Orlando Sentinel, knows this is commonplace, but feels it is sometimes overwhelming. For example, when the newspaper published the almost-16 pages of its Medicare Guide , which included special tables with precise information about plans and insurance premiums in English and Spanish, Marcial and an additional reporter did the full translation job for the printed edition in Spanish on top of their other daily news reporting tasks.

Stereotypes and discriminatory practices that have become commonplace must be deconstructed and it will take time to change newsroom culture. But to reduce the payment gap and value bilingual skills as an important skillset starts with empowered Latino journalists who know and advocate for their value.

A good starting point could be providing Hispanic students who are finishing college, as well as young female journalists, with negotiation tools and basic knowledge to approach their first employment interviews. Employers hold the upper hand, but advocating for themselves from the beginning may be the best start for an equal treatment for Latino journalists.

Next month we will start looking for partners to develop a tool kit for Latino journalists and students to help them in salary and other types of negotiations.

Comments