A black sedan with the KOMU Channel 8 logo, website and social media handles. KOMU provides a loaner car for employees. Photo courtesy of Kellie Stanfield

The power of minimal interventions to lower barriers to journalism

Small solutions can still bring about positive change

In an industry known for favoring those from wealthy backgrounds from the beginning of their journey, some journalists in newsrooms rely on the support of partners or family members. Having a safety net can be vital at every stage of the process of becoming and staying a journalist — from expensive journalism school tuition to taking low or unpaid internships, to continuing your career with a low, often stagnant, salary — especially for women and journalists of color.

These conditions have left many folks from less privileged backgrounds struggling to find pathways to work in – and stay in – the news business, and the instability and looming threat of newsroom layoffs often mean that journalism can feel like a precarious profession.

While unionizations and new revenue strategies have made marked improvements for this cause, it is also important for newsrooms to understand that sometimes minimal interventions can bring about changes, or address blind spots that are keeping folks out of newsrooms.

What are minimal interventions?

Minimal interventions are small changes that can have bigger impacts on an overall outcome or goal. The term is sometimes used in the health field to describe small things patients or providers can do to improve a prognosis, or by intervening earlier in the course of a health issue to prevent it from getting worse. Minimal interventions are also sometimes used in a business consulting context, where a consultant will analyze what small changes around the workplace can solve problems a business is encountering.

Like in the medical field, catching a problem earlier in order to intervene is an important part of what makes providing a minimal intervention an innovative process because it allows for small changes to lead to effective change, before a small problem snowballs into a big problem.

That means that early career or student level minimal interventions can be a big inspiration for professional organizations as well because student journalists ultimately end up feeding professional newsrooms after graduation. Addressing a barrier for an aspiring journalist early on can make all the difference in who becomes a working journalist.

Questions to inspire a minimal intervention to boost DEI in your newsroom

If you are interested in exploring a minimal intervention to improve equity outcomes in your newsroom, often, it starts with asking the right questions.

Here’s a list of a few jumping-off points to start a meaningful discussion about small changes for your organization.

- Take an inventory of what sorts of ‘extra’ items (clothing, transportation, office supplies, equipment) are expected to be provided by workers. Are there any ways you could supplement or provide these extras?

- Consider who has recently left your newsroom. Is there a revealing moment from an exit interview, or a common trend you’re seeing that causes retention problems? Could small changes provide some relief?

- What are some of the biggest challenges everyday that folks in your newsroom are facing? Are there resources available that maybe aren’t being connected to your staff?

- How could members of your staff help each other to be better supported? How could managers better support staff reporting to them?

- Who are the types of folks you don’t see in your newsroom? Could you create a new pipeline or outreach to these communities to let them know there is a missing space in your newsroom for them?

This is not an exhaustive list, but these questions can be a good starting point to thinking about some potential avenues towards a minimal intervention in your newsroom.

As you consider these questions, here are a few examples of some small programs and solutions that have helped increase equity in a number of professional newsrooms as well as at the college level for students entering the professional field.

Providing cell phones or phone stipends

Throughout his career, David Barreda, senior photo editor for National Geographic, has had a variety of company issued or reimbursed phones at different journalism organizations.

Barreda believes that providing phones or reimbursing for phone bills or data plans can be a way to increase equity in the newsroom, as he notes how expensive it can be to have a phone and just how often phone use is a requirement of the job.

“I do see how tied our cellphones are to work,” Barreda said. “The emails I check at night are for work. The Slack messages I respond to on my phone are for work. All of it’s happening on the phone.”

Organizations may also explore providing this type of minimal intervention for other practical reasons, like ensuring that phones their newsrooms are using for work are up to date and less vulnerable to things like hacking or surveillance.

“These cellphones are all required of us, a lot of information passes through them, it’s in the company’s best interest that they are secure,” Barreda said.

Barreda emphasized that these types of programs are not a one-size-fits-all, and there can be unintended consequences for supplied phones. “With any of these things comes added cost and behavior changes,” he said. “When you’re issued a phone, the company has an expectation that you answer that phone. There might be breaking news at the start of your shift or after it.” So a possible downside is that company-provided phones may encourage an always-on culture, which may actually contribute to less equitable working spaces and work/life balance.

Ultimately though, Barreda sees programs like these as very much in line with newsrooms purchasing equipment or having equipment stipends for employees. There are pros and cons, but it starts with recognizing what drives the need.

“Organizations need to own the fact that phones are more than a convenience, they’re also a tool,” Barreda said.

Barreda’s example of providing a phone stipend is an example from the professional journalism sphere, however, for student or early career journalists, there has been creative thinking about what sorts of programs can address equity and precarity in the profession.

Providing a loaner closet and/or a loaner car

Jeimmie Nevalga, director for KOMU-8 News and associate professor for the Missouri School of Journalism, has seen firsthand that not every student journalist has the resources to be a reporter. She’s noticed that there are many things that the profession takes for granted that workers will just have, like reliable transportation, and presentable clothing for being on air.

“I remember one instance of a student who wore the same winter clothing the entire time she was reporting. When we told her ‘We’re ready to put you on, we need you to front your story’ and she was not appropriately dressed, that was the point when we knew she didn’t really have the means,” Nevalga said. “So that for me was a little bit eye-opening.”

What’s more, Nevalga noticed a pattern that made it difficult for students to come forward. “I’ve been here 10 years and in that time there are very few students who will tell you that they’re struggling to get through school. They won’t tell you that they actually have to work to eat. They won’t tell you that they had to take out student loans to help out their families,” said Nevalga.

It started as a conversation about the students not able to come to KOMU, and Nevalga and her colleague, Kellie Stanfield, realized that there may be an opportunity to provide more of the extras many journalism students were expected to have at home.

That’s when KOMU decided to put out a call to alumni from the program, for donations to a loaner closet as a way to ensure that the cost of being presentable on air was not creating an additional burden for students learning to be on camera.

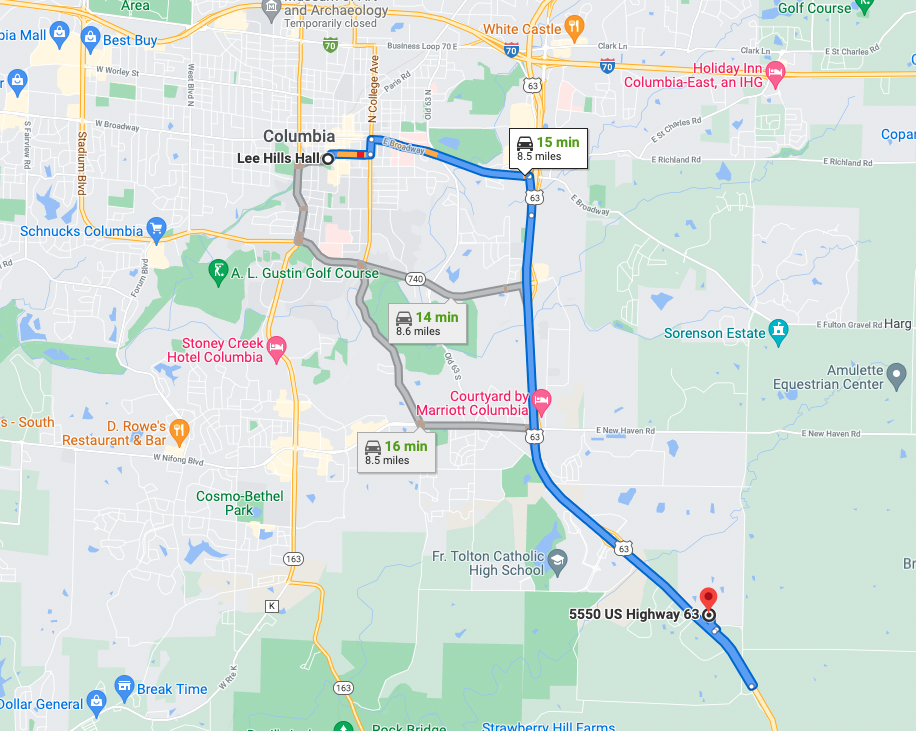

That’s not the only minimal intervention their newsroom has implemented. KOMU also provides a loaner car that can be checked out to provide students a way to get from Missouri University campus to the TV station, which is located 8.5 miles from campus, and takes about 15 minutes to reach by car.

Though Nevalga is certainly proud of the work KOMU has done with the loaner closet and the loaner car, she knows these small changes won’t solve everything for folks struggling to afford becoming a journalist.

“We need all the voices that we can bring to the table at the table. We can’t have the same people running newsrooms across the country or all you have is an echo chamber. I want someone who grew up in the big city and in a rural part of America in my newsroom. I want someone who’s first language isn’t English and someone who has varying political beliefs here. These are the people we need making the decisions in newsrooms.”

For her part, Nevalga is encouraged to see that the next generation of journalists has gotten wise to many of the practices that have fed into the kind of chew you up and spit you out culture newsrooms have fostered.

“In TV news, breaking contracts can cost money and I have students who have told me, “I’m saving money in case I need to get out of a bad situation” that’s how serious they are,” said Nevalga. “They would love the opportunity, but not at the cost of their own health and happiness.”

Providing housing for interns

Becky Cooper, managing editor for the Victoria Advocate in Texas, talked with me about a minimal intervention that her newspaper provided for photography interns. At the time the internship was still active (the program ended in the summer right at the start of the pandemic), there were a few measures The Advocate took to provide housing for interns.

The first was leveraging the existing real estate holdings of the family who owned the newspaper to provide housing for interns.

“When the photography internship first started, we had an apartment across the street from the office, where owners of The Advocate owned the house, and so the interns could stay there for free as part of the stipends they received,” said Cooper.

Eventually, the Roberts-McHaney family sold the house previously used for interns, so The Advocate used their standing in the community to negotiate another housing solution for their interns. “For two or three internship rotations we provided an apartment at a reduced rate for interns. It was a two-bedroom furnished apartment that kept the interns from having to go out and look for an apartment while they were working for us,” said Cooper.

This solution also had other added benefits for The Advocate, such as proximity to the newsroom.

“Providing the housing also gave interns a place where other staff members could meet with them and get to know them and kind of hang out with them so they weren’t just isolated in some strange apartment complex across town,” said Cooper.

Upon reflecting on this program, Cooper notes that she believes this minimal intervention increased the number of interns who could work for The Advocate, and contributed to the wide variety of interns that came to work for the paper.

“We attracted interns from all over the county, not just in Texas. They were from Kentucky and Oregon and Missouri and Iowa to name a few,” Cooper said. “I think the word got out pretty quickly that The Advocate had this internship and what we offered and were able to do and that’s why I think we had a lot of interest from our photographers.”

However, Cooper stressed that while she might recommend other newsrooms explore providing housing for interns, there may be other considerations to keep in mind for this type of minimal intervention. Some of these can be legal, such as checking about the rules a corporation may have for providing housing.

It’s also important, says Cooper, to weigh if providing housing is the best solution for addressing low pay, which is the root issue driving the need.

“If we offered the internship program again for photographers and or reporters, I would suggest that we offer them either a reduced rate apartment again, or a more livable salary so they can rent their own apartment,” said Cooper.

Why focus on small solutions if the problems are big?

Minimal interventions can be a useful and innovative stop-gap measure for newsrooms who are looking to create opportunities when they have little or no decision making power about how their colleagues get paid or what sorts of issues are contributing to the precarity of the profession.

Some of these changes are about making pathways towards becoming a journalist more accessible, but others deal in retaining good, and crucially, more diverse talent. In this way, minimal interventions can also be a way to address problems that lead to lack of retention, among journalists from marginalized backgrounds for newsrooms.

Since not every newsroom has the same bandwidth to do something as drastic as providing housing or a loaner car, there are other, less costly minimal interventions that can help level the playing field for journalists from less privileged backgrounds.

When we put out a call about minimal interventions that the industry could implement, we heard many suggestions. Ideas like:

- Discontinuing unpaid internships

- Setting clear and fair social media policies

- Discouraging a culture of performative objectivity from reporters

- Instituting a pay transparency system

- Offering more flexible work days and hours

- Giving better parental leave

- Focusing more on underserved communities

Many of these ideas are about addressing different facets of a core problem in journalism, which comes back to the fact that many journalists generally need to be paid more. But some of these ideas, such as focusing more on underserved communities and discouraging performative objectivity, are also about not making less privileged journalists feel punished for their backgrounds.

Crucially, it’s also important to point out that some of these ideas require a monetary investment, while others are free to implement, furthering the argument that implementing a minimal intervention can be a good fit for any kind of newsroom, even those strapped for monetary resources.

The philosophy of minimal intervention is this: As long as you’re affecting positive change in some way, there’s no such thing as thinking too small.

Comments