Photo: Susan Stellin

Reporting on alcohol and drinking risks

Years of contradictory headlines about whether moderate drinking is harmful or beneficial for different health outcomes has left many people frustrated and skeptical

Last month The Washington Post published an article with the headline, “No amount of alcohol is safe, at least for dementia risk, study finds.” Among the more than 1,000 comments, some predictable responses emerged, which the Post’s AI tool helpfully summarized (bold added):

“The comments reflect a range of perspectives on the research suggesting that even light alcohol consumption can increase dementia risk. Some individuals have reduced or quit drinking due to health benefits, improved sleep, and personal experiences with dementia in their families. Others express skepticism, citing personal anecdotes of relatives who drank without developing dementia, or questioning the study’s methodology and the role of genetics and other factors. There is also a sentiment that life involves various risks, and some prioritize enjoyment over strict avoidance of alcohol. Overall, the comments highlight diverse attitudes towards alcohol consumption and its potential health implications.”

In fact, the study itself is much less definitive than the Washington Post headline, with mixed conclusions based on different approaches the researchers used for their analysis.

As one reader dryly noted:

“I am sure that many will continue to drink moderately and that the next study will confirm or deny the conclusions of this study, much as this one denies the conclusion of the previous one.”

That frustrating pattern tends to characterize research about moderate alcohol consumption, which is tough to study over long periods of time. How accurately are people reporting their drinking levels? How is moderate drinking defined? Does it make a difference if someone drinks whiskey or wine? What other factors influence the development of a notoriously difficult to research disease like Alzheimer’s?

We may never know for sure if drinking a few glasses of wine a week has a minimal health impact for most people—even though not drinking alcohol at all is arguably a safer choice, particularly during pregnancy and for those with certain health conditions.

So how can journalists help people make informed decisions about their drinking levels? Here are some suggestions.

Mention how many people don’t drink alcohol

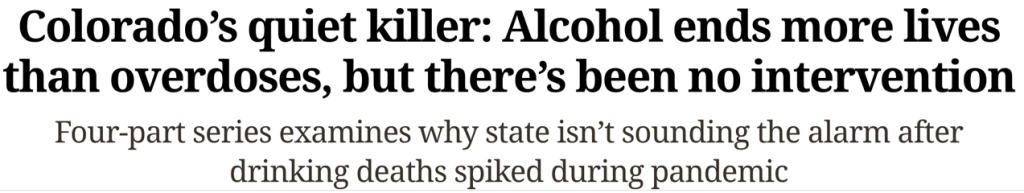

When I came across this graphic in the Check Your Drinking Tool on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website, I was surprised to see that half of people 21 years and older in the U.S. don’t drink alcohol. Yet other sources support that finding.

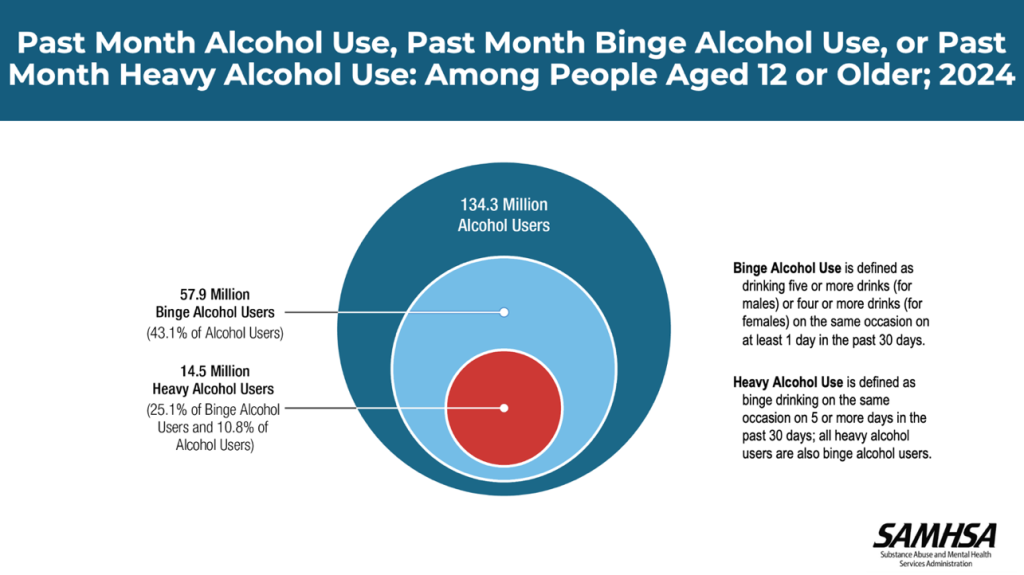

The 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported that about 47 percent of respondents aged 12 or older had used alcohol in the past month, a number that’s been pretty consistent for the past few years.

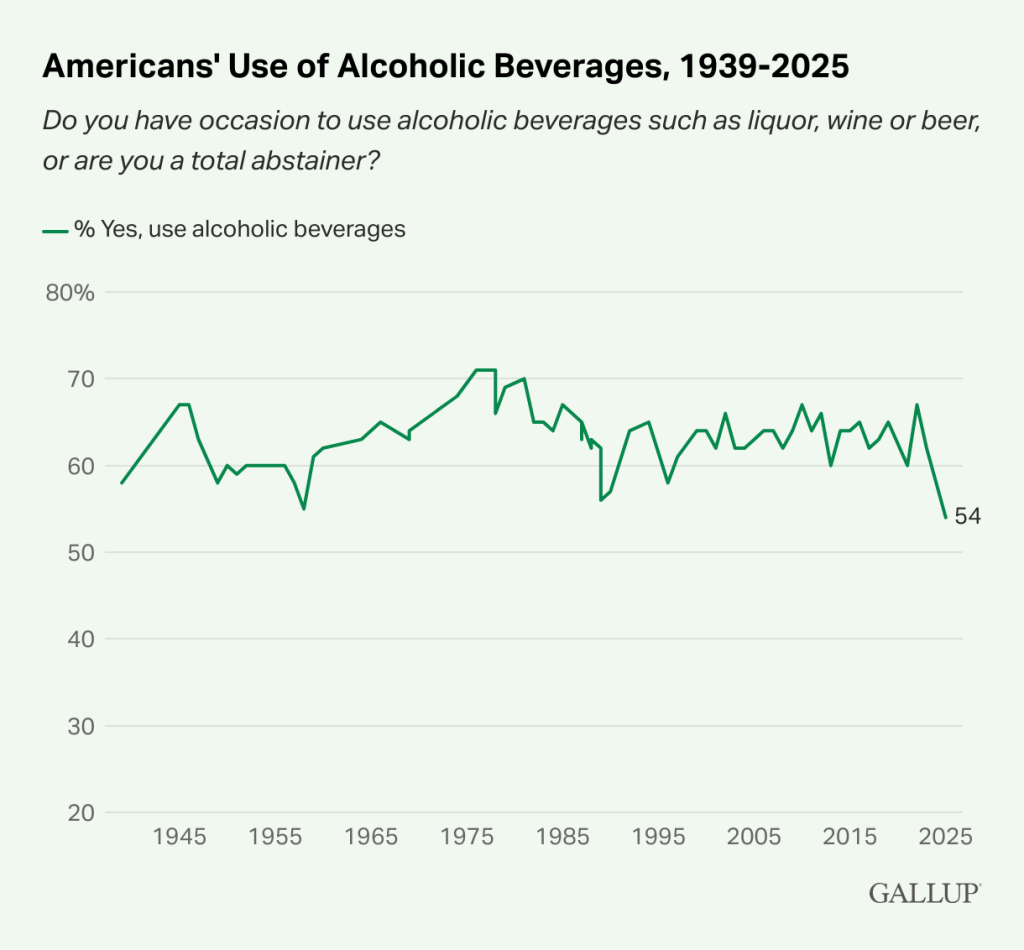

In August, Gallup released the results of its annual Consumption Habits survey finding that the percentage of U.S. adults who say they consume alcohol is now 54 percent—the lowest level since Gallup began tracking this in 1939. Surveys don’t always reach those with higher drinking rates, like people experiencing homelessness, but avoiding alcohol is more common than many people assume.

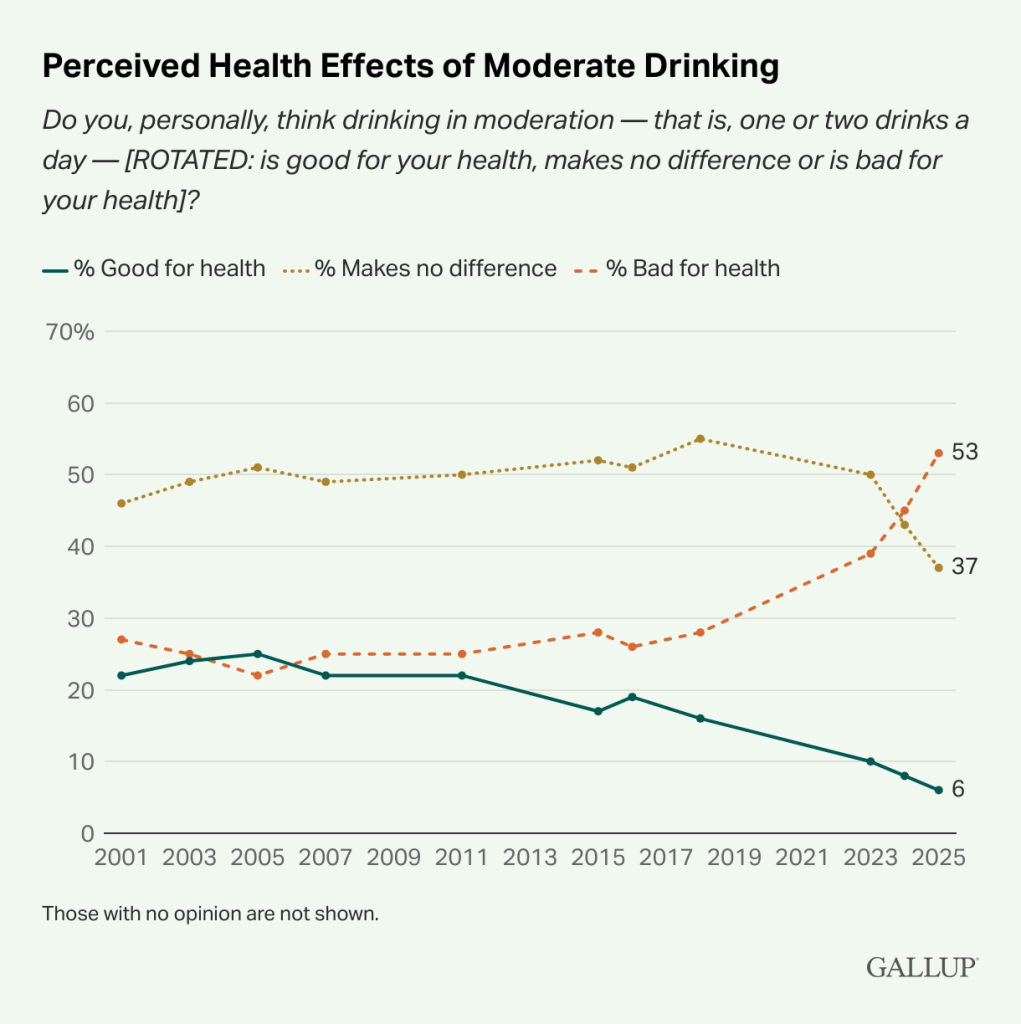

Gallup’s survey also found that 53 percent of respondents say drinking in moderation, described as “one or two drinks a day,” is bad for one’s health, while 6 percent thought it was good for one’s health and 37 percent believe it makes no difference. That reflects changing views in recent years.

Historically, news and entertainment media have presented drinking alcohol in a positive light, with advertisements that promote that view. Journalists themselves are often depicted as heavy drinkers in books and films. For news outlets, showing data that normalizes the choice not to drink alcohol would help those who sometimes feel social pressure to join in, or stigmatized for ordering a seltzer.

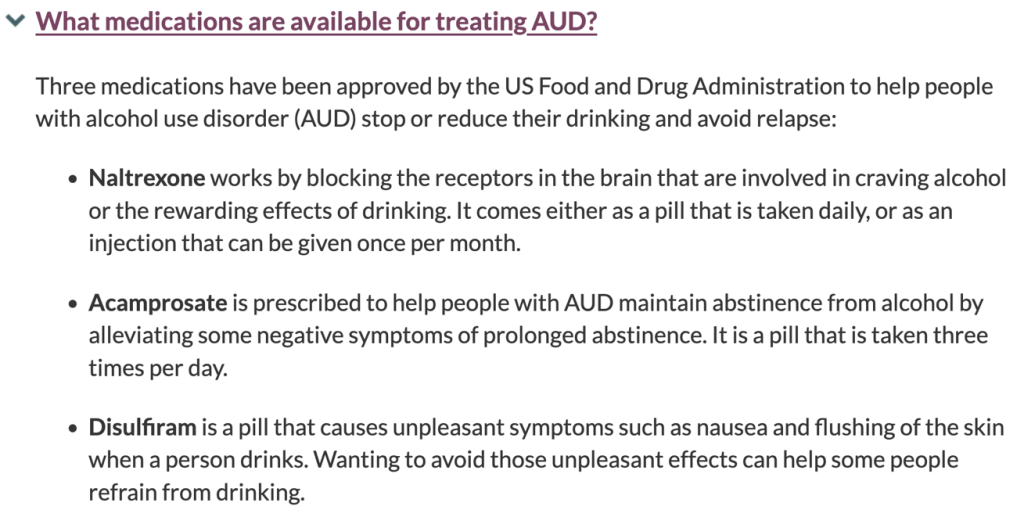

Educate people about drinking guidelines and serving sizes

According to the 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines, women should have one drink or less in a day and men should have two drinks or less in a day. That’s generally considered moderate drinking, but still leaves a wide range between a man who has three bottles of light beer a week and one who has 14 glasses of vodka.

The new national dietary guidelines were expected to be released this fall, but have been delayed due to the government shutdown. There has been some speculation that advice about drinking levels may be removed from the guidelines, which are now supposed to be released by the end of the year.

For now, the CDC and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) both have graphics about what is considered a standard drink, which can be linked to or included in news stories. That would help educate people about how much alcohol may be in common serving containers.

For instance, NIAA’s drink size calculator indicates a 21-oz ballpark souvenir cup can hold nearly two standard servings of beer, while a 25-oz bottle of wine has five standard drinks per container.

Share data about binge drinking and heavy alcohol use

NIAAA describes binge drinking as drinking five or more alcoholic drinks on one occasion for men, and four or more for women. Even fewer drinks may raise the blood alcohol concentration above 0.08%, the legal limit for noncommercial drivers in most states.

Heavy drinking is defined as consuming five or more drinks on any day or 15 or more per week for men, and four or more drinks on any day or 8 or more per week for women.

Both of these drinking patterns increase the risk of alcohol use disorder (AUD), which can be mild, moderate, or severe depending on how many of 11 criteria someone meets. In 2024, about 28 million people aged 12 or older met at least two criteria for an alcohol use disorder, though nearly 60 percent of them had a mild AUD.

People with heavy, binge, or risky drinking patterns are most at risk of health and other harms. That deserves more news coverage like this 2024 series by the Denver Post:

Include resources to help assess alcohol consumption

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening adults for unhealthy alcohol use in primary care and offering anyone engaging in risky or hazardous drinking brief counseling and potentially a referral to treatment.

In healthcare settings, the screening tools typically used are the NIAAA Single Alcohol Screening Question — ”How many times in the past year have you had 4 or more drinks in a day (for women) or 5 or more drinks (for men)?” or the AUDIT-C test, which includes three questions.

There are also tools people can use on their own, like the CDC’s Check Your Drinking Tool, which asks a few multiple choice questions, then gives personalized feedback based on the responses.

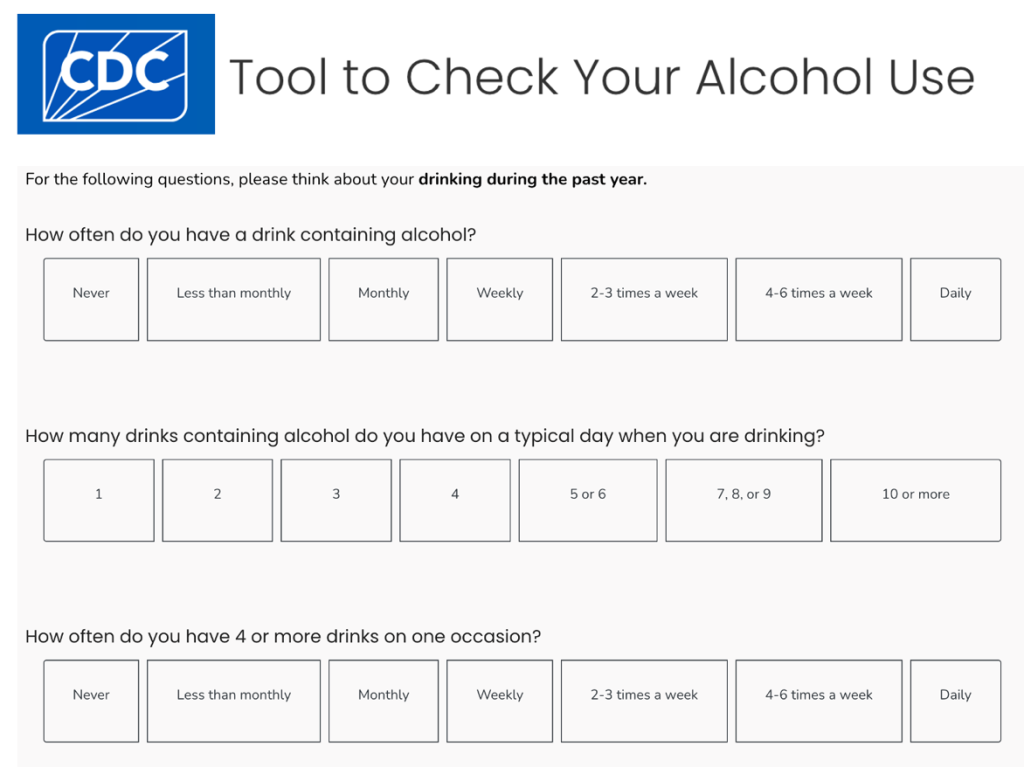

After asking how much someone drinks, the tool asks, “What motivates you to drink less or stop drinking?” (avoid hangovers, save money, sleep better, etc.) and “What are some barriers you face in drinking less alcohol?” (stress, social situations, boredom, habit, or coping).

Then it asks about goals: “How many fewer drinks would you like to have?” (per week or per drinking occasion) or “I want to stop drinking altogether.”

Finally, it presents an individualized plan based on the motivations, barriers, and goals submitted, with suggestions about other ways to deal with challenges like socializing with less or no alcohol.

Similar tools are available from NIAAA’s Rethinking Drinking site and Canada’s Know Alcohol campaign. There are also apps people can download and use to create and track drinking goals.

Importantly, the focus of these tools is educating people about alcohol and helping them make informed decisions about how much to drink — not promoting abstinence for everyone.

Raise awareness about established drinking harms

CDC data indicates there are 178,000 alcohol-related deaths in the U.S. every year, well above drug overdose fatalities which have gotten much more media attention.

About two thirds of these deaths are due to chronic conditions that develop with drinking over time, including certain types of cancer, heart disease, liver disease, and alcohol use disorder. A third are due to binge or risky drinking on one occasion, leading to motor vehicle crashes, alcohol poisonings, deaths by suicide, and alcohol-involved drug overdoses. (Mixing alcohol with drugs like opioids increases the risk of a fatal overdose.)

The CDC’s Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) tool offers more detailed information about alcohol-attributable deaths for the U.S. and individual states. The agency has also published state fact sheets with data for all 50 states and the District of Columbia about alcohol consumption and policies that can help prevent excessive alcohol use.

Beyond fatalities, alcohol use increases the risk of injuries, violence, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, mental health conditions, and other health harms.

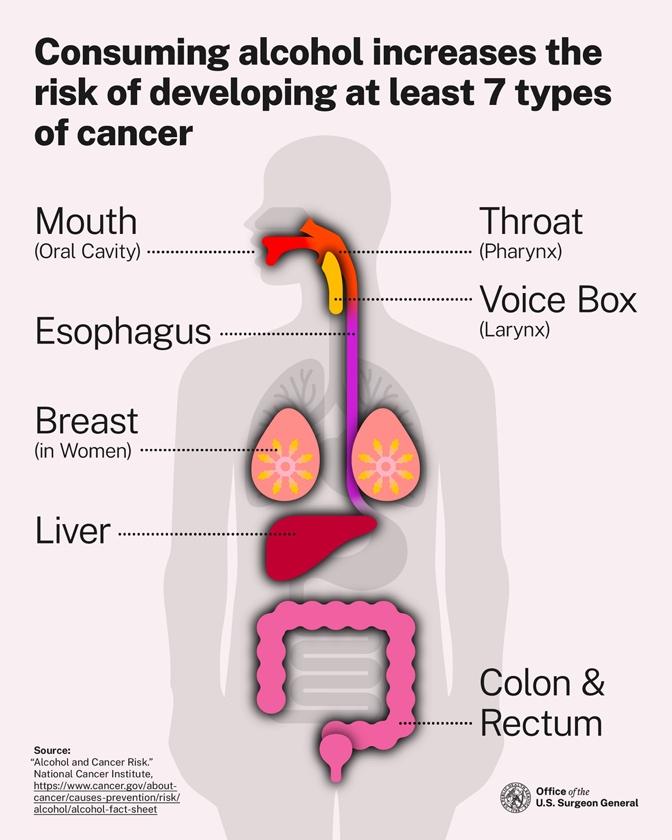

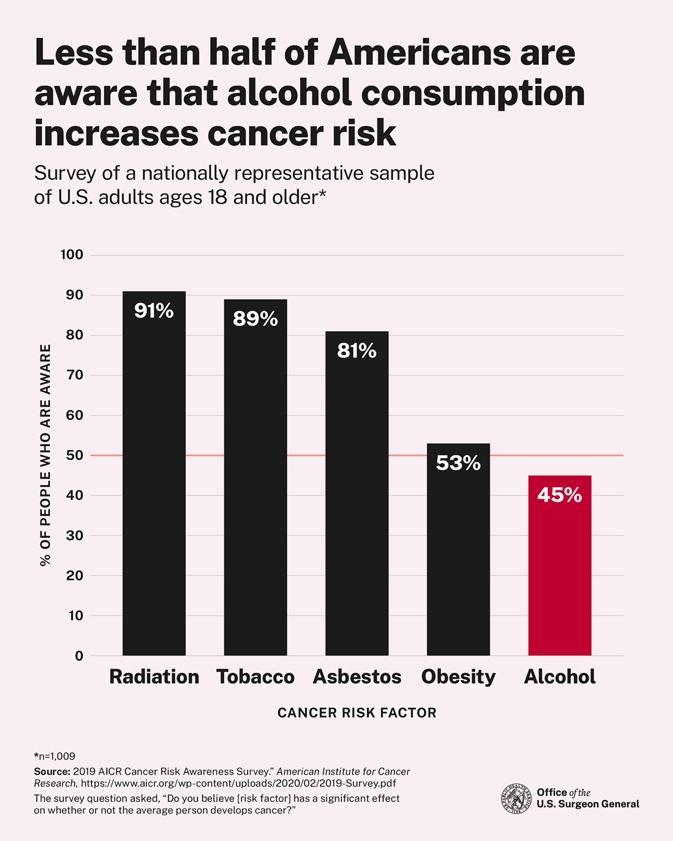

In January, the U.S. Surgeon General published an advisory about alcohol and cancer risk, noting that alcohol is the third leading preventable cause of cancer in the U.S., after tobacco and obesity, contributing to nearly 100,000 cancer cases each year.

As with the link between smoking and cancer, which was initially contested even by medical professionals before it became widely accepted, research examining alcohol’s impact on various health conditions has sparked debate.

A Review of Evidence on Alcohol and Health, published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in late 2024, was more equivocal about the link between moderate alcohol use and cancer, though criticized for potential conflicts of interest.

After noting the social, economic, and other benefits of alcohol—which are important to many people—the report did acknowledge, “Research on the health effects of moderate drinking is challenging.”

Report on effective treatment options and sources for help

For individuals and families navigating problems with alcohol, there can be a perception that quitting drinking is the only option, and that treatment means a residential rehabilitation program or participating in an Alcoholics Anonymous group.

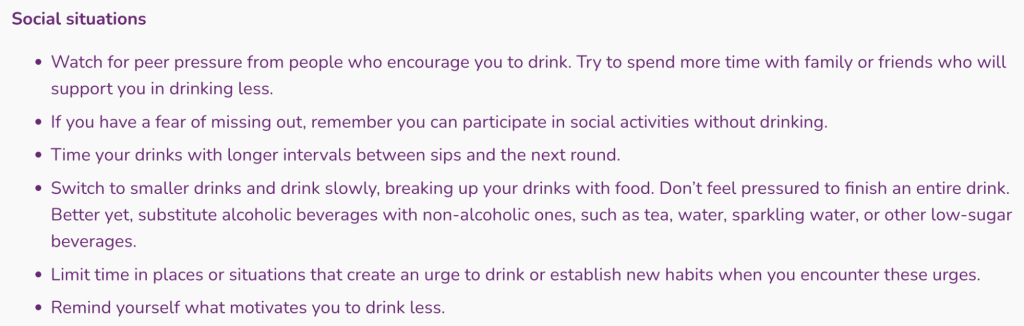

Both approaches have helped many people, but there are other options available through outpatient programs and counseling, as well as medications that a doctor can prescribe.

NIAAA’s Alcohol Treatment Navigator gives an overview of evidenced-based behavioral treatments for alcohol use disorder, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, or contingency management. It also offers information about the three medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating alcohol use disorder: naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram.

While these medications tend to be prescribed for people with moderate or severe alcohol use disorders, studies suggest very few people receive them.

There are also efforts to help people reduce their drinking before they develop a severe problem. For instance, a recent randomized controlled trial found that a culturally adapted behavioral intervention delivered by Spanish-speaking community health workers significantly reduced unhealthy alcohol use along Latino/a individuals.

Reporting on these types of initiatives can help raise awareness about promising approaches—and balance reporting that tends to focus on unethical for-profit rehabs.

To that end, including tools that can help people find quality care is a public service that can make a meaningful difference to readers, listeners, and viewers who often don’t know where to turn for advice.

Many state and local public health departments have websites that educate people about treatment options and help connect them with providers and programs. The NIAAA’s treatment navigator also has tools to search for alcohol treatment programs, therapists with addiction specialties, and doctors who are board-certified addiction specialists, with the option to filter the results to view accredited programs.

NIAAA recommends 10 questions to ask providers and advice on choosing quality care, as well as downloadable images about the Alcohol Treatment Navigator that can be embedded in stories.

With so much focus on opioids in the past decade, media coverage of unhealthy or risky drinking patterns has taken a back seat. The debate over moderate drinking may be unresolved, but there are plenty of topics to report on that are much more certain—and can help improve the lives of millions of people.

To sign up for email alerts when these monthly articles are published or offer feedback about the Covering Drugs toolkit I’m developing, you can fill out this form or click the link below. I’m especially interested in finding out what questions or topics journalists would like to see included, including challenges reporters have encountered finding information or data. I also welcome suggestions from researchers, service providers, policymakers, advocates, and people personally impacted by substance use and addiction.

Cite this article

Stellin, Susan (2025, Nov. 18). Reporting on alcohol and drinking risks. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/reporting-on-alcohol-and-drinking-risks/

![What is considered a "drink?" U.S. standard drink sizes. 12 ounces: 5% ABV beer = 8 ounces 7% ABV malt liquor = 5 ounces 12% ABV wine = 1.5 ounces 50% ABV [80 proof] distilled spirits [examples: gin, rum, vodka, whiskey]](https://rjionline.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2025/11/stllins25111804-1024x558.png)