Illustration by Susan Stellin, adapted from multiple depictions of the pyramid of evidence.

Evaluating research about drugs and addiction: The danger of a single study

Asking key questions when evaluating studies can help improve the quality of reporting about research

A few years ago, I started noticing a statement that was frequently used to describe one of the benefits of syringe service programs (SSPs): that people who utilized them were “five times more likely to enter treatment” and “three times as likely to stop using drugs” as people who didn’t use them.

It caught my attention because it was both so specific (three or five times) and so broad (people who do or don’t use SSPs), yet there has not been robust data collection about treatment engagement by many of these valuable, under-resourced programs.

Most references in news articles linked to the CDC’s page titled the “Safety and Effectiveness of Syringe Services Programs,” which is no longer online.

That CDC page previously referenced a study by Hagan et al. published in 2000 in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment: “Reduced injection frequency and increased entry and retention in drug treatment associated with needle-exchange participation in Seattle drug injectors.”

For that study, researchers collected data in the late 1990s in Seattle, specifically focusing on injection drug users and methadone treatment. What they found was more nuanced than it was later described, with some differences between those who had never used a needle exchange, were ex-users, new users, or current users. Injection drug users who had formerly used the exchange were more likely to remain in a methadone treatment program and to reduce or stop injecting — which makes sense, since they stopped going to the SSP to get syringes. New users of the SSP were five times more likely to enter methadone treatment than people who never used its services.

Despite being more than 25 years old, some methodological limitations, and many changes in drug use patterns and treatment services since the late 1990s, this study has been cited in research more than 40 times just in the past five years. Versions of the “syringe service programs” and “five times more likely” statement appears on thousands of state government, advocacy, medical, and media websites; it even shows up in an AI summary.

It may be that people who visit syringe service programs are more likely to enter treatment for a substance use disorder, compared to those with similar characteristics (demographics, drug use patterns, etc.) — especially if the programs receive financial support to offer medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). Data published in 2023 by the California Overdose and Harm Reduction Initiative (COPHRI) reported that participants from SSPs that offered on-site medications were twice as likely to be currently prescribed buprenorphine and methadone as those where on-site access was not available. A review by Jakubowski et al. published in 2023 offered a more updated summary of research examining syringe service programs as an entry point for treatment.

I’ve volunteered at a syringe service program for several years and have visited others, witnessing their many benefits that are tough to quantify — such as providing a place where people who feel deeply stigmatized are treated well and get connected to services, including substance use treatment and help with basic needs (e.g. bathrooms, food, and internet access). But it’s still unsettling that a single study from long ago has led to repetition of a claim that took on a life of its own, and it’s not uncommon for this to happen.

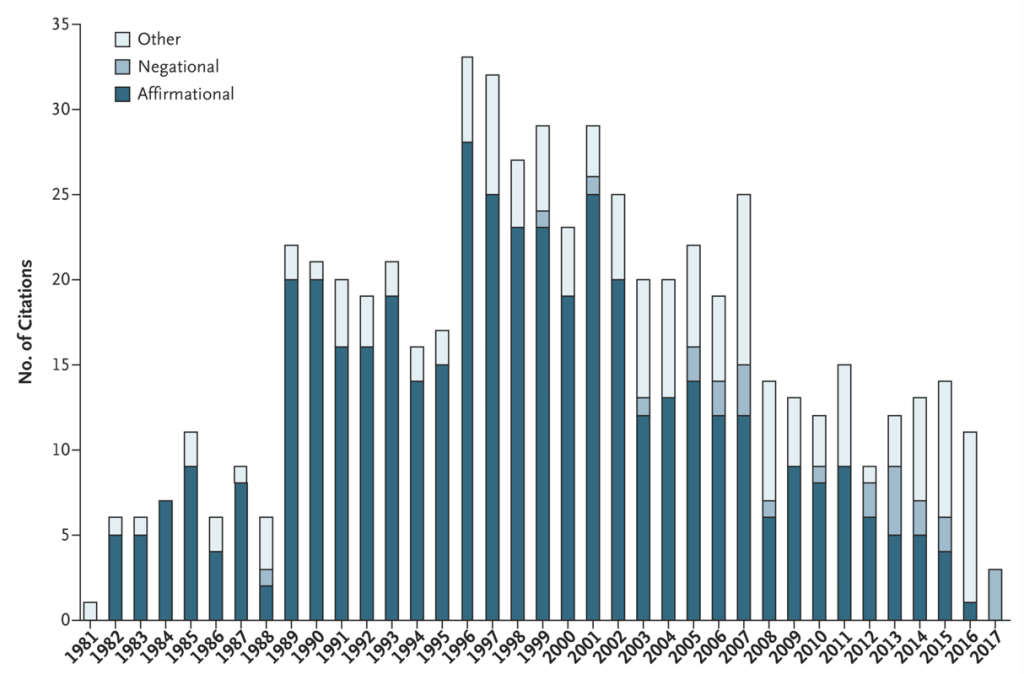

A more familiar example is how a one-paragraph letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1980 was referenced as evidence that the risk of addiction was low when opioids were prescribed for chronic pain. In 2017, researchers published an analysis finding that this letter had been cited by other studies over 600 times, with more than 70 percent citing it as evidence that addiction was rare in patients treated with opioids.

In his book, Blind Spots: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health, Dr. Marty Makary, now the commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drugs Administration, discusses examples of what he describes as medical dogma: flawed research that became accepted and vigorously defended, about opioids, hormone replacement therapy, and other topics.

“One of my greatest concerns is that today’s public health and medical experts — and certainly the media — have lost the ability to critically appraise research quality,” he writes.

Notwithstanding Dr. Makary’s role in the executive branch at a time when it is defunding research, politicizing science, and promoting misinformation, the point he makes predates the current administration.

Spin, defined by one systematic review as “reporting practices that distort the interpretation of results and mislead readers so that results are viewed in a more favourable light,” has long been an issue with published research. And in recent years, social media has played a key role in amplifying flawed research, misinterpreting findings, and presenting personal perspectives as evidence.

So now more than ever, it is important for journalists to critically vet studies and carefully report on their findings—with particular caution about reporting on a single study. To paraphrase a point the novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie made in her impactful TED talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” the problem with a single study is not necessarily that it is untrue, but that it is incomplete. Scientific research is a process that is always evolving, and journalists can help the public understand that—finding a middle ground between rejecting science and blind faith.

Reporting on research: Questions to ask

Below are some questions to consider when interpreting research, with examples relevant for reporting on treatment for a substance use disorder or addiction. Resources that offer general advice about evaluating scientific research are listed at the end.

What factors or variables are being measured?

For research about treatment, the variables measured can range from outcomes like retention in treatment or medication adherence to reduced substance use, abstinence, overdose, and other factors related to physical or mental health, quality of life, or criminal justice involvement. It’s important to consider whether the factors being evaluated align with outcomes that are public health priorities, less complex to study, or designed based on the availability of funding for research, and how those may differ from the goals individuals, their families, and communities prioritize.

Who was included in the evaluation? Who was excluded?

Some research studies exclude participants who use more than one substance, have mental health conditions, or for other reasons, which means the results may not apply to a broader population. Smaller sample sizes or more homogenous participants also impact study or survey results, with larger, more diverse samples more likely to reflect real-world outcomes. Studies using animals can reveal helpful information and ideas for further research, but the results can’t be assumed to apply to human participants. (See Rat Park: How a Rat Paradise Changed the Narrative of Addiction for a critique of the “Rat Park” studies widely cited in news and social media.)

Who is in the group being compared to the population receiving the treatment or service studied?

Ideally, the two groups being compared are similar, except that some receive the intervention (like cognitive behavioral therapy), and some don’t, which may be described as “treatment as usual.” Some studies compare two types of treatments, like outcomes for people taking methadone vs. buprenorphine. If the characteristics of people in the treatment group are different from the comparison group, that would introduce additional variables that can influence the results.

How long were participants followed?

The follow-up period for research studies is often measured in months, so evaluating outcomes a few months after treatment is completed would not align with the typical timeline of recovery: one year for early recovery and five years or more for stable recovery.

What year was the data collected, and then published?

Particularly given the rapidly changing drug supply and shifts in drug use patterns, older data may not accurately reflect the efficacy of treatments and other interventions in the current era. For instance, an evaluation of medications for opioid use disorder that focused on people using prescription opioids would not be generalizable to people primarily using fentanyl. The references cited in a study may also be outdated.

What were the findings and how are they described?

Comparing the abstract with the results and discussion sections of a study can reveal different things highlighted in all three places, and the limitations section of a study can raise important red flags. Many studies identify associations or correlations that should not be interpreted as causation. For instance, someone drinking coffee every morning might be associated with the sun coming up, but it doesn’t cause the sun to appear.

Who funded the study/researchers? Are there any conflicts of interest?

Consider who funded the study and its authors and whether there are any potential conflicts, such as financial relationships with industry through past or present employment, consulting work, or stock ownership. Sometimes not all conflicts of interest are disclosed in published studies (publication policies vary and may only ask about recent work). The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) has more information about disclosure of financial and non-financial relationships and activities, and conflicts of interest.

Sources of advice for reporting on research

A Consumer’s Guide to Research on Substance Use Disorders

This series by Jason Schwartz, an addiction professional and social worker who created the Recovery Review blog, explores questions intended to help people understand research about substance use disorders. Each part of the series offers more detail about many of the questions described above, with links to relevant examples. The whole series can be downloaded as a PDF.

How to Gauge the Quality of a Research Study: 13 Questions Journalists Should Ask

This tip sheet published by The Journalist’s Resource describes 13 questions that can help identify red flags in research, with advice about scrutinizing studies that policymakers and elected officials cite to defend their positions on particular issues. A related post, Six Tips to Help Journalists Avoid Overgeneralizing Research Findings, includes a discussion of the risks of relying on artificial intelligence tools to summarize research.

Created by The Open Notebook in collaboration with the Reynolds Journalism Institute (which funded the Covering Drugs guide I’m developing), the Science Reporting Navigator explains how to search for, access, and vet scientific papers. It also offers advice on interviewing scientists, interpreting data, and contextualizing findings.

Based at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), SciLine is a free service with reporting resources and courses for journalists, as well as advice for scientists about working with the media. Its mission is to enhance the amount and quality of scientific evidence in news stories.

Started in 2010 by journalists Ivan Oransky and Adam Marcus, Retraction Watch is a blog and searchable database that tracks, analyzes, and reports on retractions of scientific papers, expressions of concern, and related issues of research misconduct.

To sign up for an email alert when the Covering Drugs toolkit I’m developing is published, you can fill out this form or click the link below. All of the 2025-2026 RJI fellowship projects will be presented during a webinar on March 5, 2026. Register at: bit.ly/rjifellowspresent.

Cite this article

Stellin, Susan (2026, Feb. 9). Evaluating research about drugs and addiction: The danger of a single study. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/evaluating-research-about-drugs-and-addiction-the-danger-of-a-single-study/