‘Touching the Future:’ Q&A with a pioneer on the vision and future of tablets 10 years after iPad

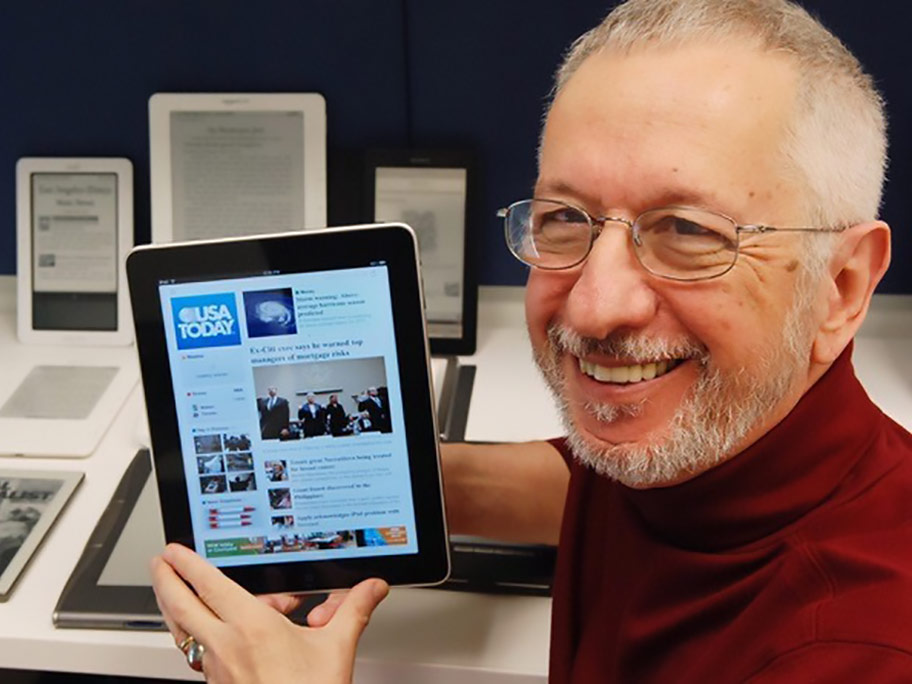

Ten years have elapsed since Roger Fidler touched for the first time the thin, lightweight device he had been dreaming about since 1980.

Fidler, an internationally recognized new media visionary and pioneer, had this idea for an electronic alternative to ink printed on paper that would revolutionize newspaper and magazine publishing. In the ‘80s, it was disregarded as a “whack-ball” idea.

Today, the Apple iPad tablet Fidler held on April 3, 2010 — the first day the device went on sale — is commonplace, just as he predicted in his 1997 book, “Mediamorphosis: Understanding New Media.” Nearly a half billion units were sold by Apple in the past decade; well over 2 billion more similar tablets were sold by competing companies.

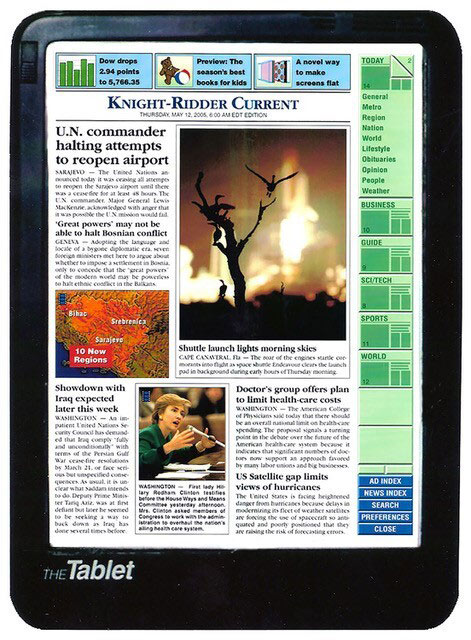

His vision began to take shape while working in Miami as a member of the project team developing Viewtron, the Knight-Ridder newspaper chain’s pioneering consumer online service. As the chain’s corporate director of new media development and head of its Information Design Laboratory in the first half of the ’90s, he actively pursued his tablet vision, which by then was being taken seriously by media and technology companies worldwide. In 2005, as RJI’s inaugural fellow, he created a prototype tablet news edition for the Columbia Missourian.

While reading news has been and continues to be one of the most popular leisure-time uses for tablets, the digital publishing revolution that Fidler once embraced as the savior of newspapers has, as he states in the epilogue of his latest book, “relentlessly deviated into their nemesis.”

Fidler’s latest book, “Touching the Future: My Odyssey from Print to Online Publishing,” chronicles the world-changing transition from Gutenberg-age printing to digital-age online publishing during his lifetime.

In this Q&A, he reflects on his efforts to realize his tablet newspaper vision and the future of newspapers and print journalism.

The “Tablet Newspaper Vision” video you produced at the Knight-Ridder Information Design Lab in 1994 showed actors reading a digital newspaper on a tablet mockup that looked remarkably similar to the iPad introduced by Steve Jobs 16 years later. In the ’90s, you believed tablets would be a “game changer” for newspapers and print journalism around the beginning of the new century. Why didn’t that happen?

FIDLER: In the early ’90s, I saw tablets as a logical outgrowth of the digital publishing revolution, which newspaper companies had helped to launch and lead in the latter third of the 20th century, that would revitalize print journalism. In my mind’s eye, tablets and printing on mobile screens were the ultimate digital-age replacement for the last vestiges of industrial-age publishing — printing presses and delivery vehicles. The underlying technologies required to produce tablets as I had envisioned them at affordable prices, however, were not available until well after the year 2000. By the time Apple introduced the iPad, few newspapers had the wherewithal to pursue innovative tablet newspaper concepts. While I had been warning publishers of the coming digital disruption since the 1980s, the precipitous decline of daily newspapers around the world in the first decade of this century and the demise of Knight-Ridder in 2006 took me by surprise.

The rapid development and adoption of the internet and web, broadband wireless telephony and local area WiFi, and high-capacity solid-state memory chips proved to be the real game changers, but not in the way I had envisioned. Instead of revitalizing print journalism and newspapers, these technologies contributed to their decline. They were not the only contributors, however. Pressures from investors to maintain high profit margins, the loss of lucrative classified advertising revenue to Craigslist and other online services, crippling debts accrued from acquisitions, the Great Recession of 2008, and the widespread adoption of online shopping and social media were among the more consequential factors.

During your RJI fellowship in the spring of 2005, you conducted a 10-week field test of your tablet newspaper concept using content from the Sunday Missourian. This was a full five years before the iPad was introduced. Were you too early?

FIDLER: That may be the story of my life. Nearly all of the visions I pursued in my career took between five and 30 years to be realized. A couple of my visions still have not been fully realized. One of my colleagues likened me to Johnny Appleseed, the legendary nurseryman who planted and nurtured apple trees in several north-central states in the early 19th century believing that apple orchards would become an important crop for future generations.

With the Missourian tablet newspaper project, I was planting another seed. More than 5,000 people from across the nation and 12 countries registered to get the weekly digital editions during the field test. Based on our follow-up research, most people read them on laptop computers, but a significant percentage read them on the pen-based tablet PCs introduced by Microsoft in 2000. The Missourian continued to produce digital editions in the tablet format I called eMprint until the spring of 2007. Many of the interactive mixed-media features demonstrated in those digital editions were adopted by newspapers for their initial tablet editions three years later.

You have described your tablet newspaper concept as a hybrid of print and online. What were some of its distinctive features?

FIDLER: I designed the magazine-size eMprint format to preserve the visually rich presentation and page-based structure of a printed newspaper while taking full advantage of the hypermedia and links used by websites. Like newspapers, the stories, photos, and graphics were curated and laid out by editors within topical sections, and display ads were juxtaposed with stories. Like websites, ads and stories could have hyperlinked layers of additional content as well as links to other online content. With eMprint, each edition was a self-contained, finite package that could be saved and read interactively offline on any computer anywhere, at any time using the free Adobe PDF Reader app.

Why didn’t newspapers adopt your eMprint format for the iPad?

FIDLER: Actually, versions of my format were initially adopted by several newspapers, including The New York Times, USA Today, and The Daily, which Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. developed specifically for the iPad in 2011. However, by then electronic newspapers were rapidly morphing into personalized news apps that replaced edition-delayed delivery, human curating, page layout, and distinctive typography with nearly immediate 24/7 access, data-driven algorithms, dynamic templates, and generic fonts. The established newspaper editorial and design principles that I once espoused and incorporated into the eMprint format were effectively rendered superfluous.

Most consumers now appear to have opted for reading news on large-format smartphones. Did the iPad have the longevity and impact on news delivery that you expected?

FIDLER: My wife and I may be a dying breed of news junkies. We still read home-delivered printed editions of The New York Times and Missourian every morning with breakfast. We also read news throughout the day on our large-format iPhone and iPad. The iPhone has the advantages of being small enough to fit in pockets and purses, and of having broadband cellular access. Now, because the coronavirus pandemic has confined us to home, we are using our iPad much more frequently for reading news, in addition to doing online shopping and staying in contact with our friends around the world. So, to answer your question: While tablets have not had the impact on news delivery that I once expected, I’m reasonably confident that they will remain a popular component of the mobile news ecosystem for the foreseeable future.

So, how much longer do you believe printed newspapers will survive? And, how do you see the news media and journalism evolving in the next 30 years?

FIDLER: This past September, when I finished my latest book, I was cautiously optimistic that some newspapers would survive and that a few would continue to publish printed editions for at least another 10 years. In the past couple of weeks, any optimism that I might have had about the future of newspapers and the news media has dissipated. How this pandemic and the economic and political chaos that are sure to follow will change the world as we have known it is beyond anyone’s ability to predict today. I can only hope that truth-seeking journalism, in some form, will continue to play a vital role in the new world that emerges.