Changing the language around incarceration

Instead of “inmate,” use “person in prison” or “person who is incarcerated”

The Associated Press Stylebook, as of yet, provides no guidance on the language around the incarcerated. If the media were to follow the person-first approach, the practice should be to describe people in prison as “a person who is incarcerated,” “person in prison,” or “incarcerated person.” But when FWD.us conducted a search of stories published in 2020 in eight newspapers and wire services including in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times and the Associated Press, it found more than 10,000 articles that used the terms “inmate,” “felon,” or “offender,” compared to 480 articles that used people first terms.

As a journalist, I understand the reasons why — at first glance, the terms seem neutrally factual. More importantly, the words are short, succinct and easy to fit into sentences and headlines. But as I do more and more work with writers inside, it doesn’t feel right. If each of us were truly honest, how many of us would not cringe or react with fear if they were told that someone had been an “inmate?”

“Words are everything,” Norris Henderson, the founder and executive director of Voice of Experience, a New Orleans-based criminal justice advocacy organization by formerly incarcerated people, stated. “It becomes that adjective that denies you every opportunity that people have been preparing for.” He added that it also feels like people who have been incarcerated are being told to stay in their place.

When I started my fellowship at Reynolds Journalism Institute, I had a goal of creating a framework for collaborative journalism between Prison Journalism Project’s writers and other media organizations. The past year’s work has highlighted a challenge for us to tackle in 2022: helping to change the language used to describe people who are incarcerated.

In an occurrence that is all too frequent, we encounter situations where we would work with an incarcerated writer to deliver a powerful and eloquent article only to have a publication refer to them as an “inmate.” In articles written about the Prison Journalism Project, our organization would often be described as one that works with “inmates.” Each time, we would kick ourselves wishing we had the foresight to discuss the language around incarceration beforehand.

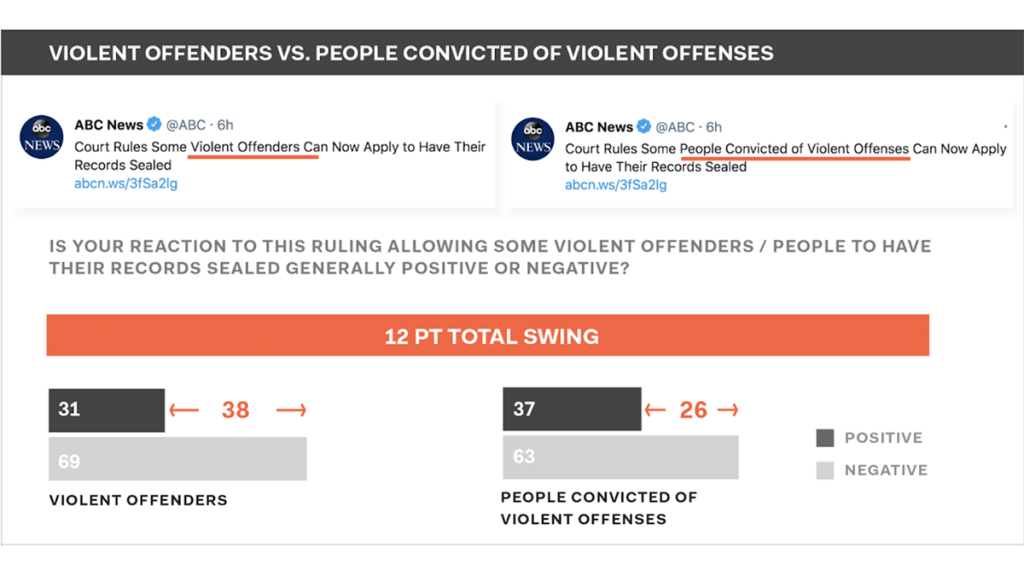

There is compelling evidence that shows the negative impact of these words on public opinion. In a poll by FWD.us in partnership with Benenson Strategy Group, respondents were evenly split between neutral associations like “needs rehabilitation” and “made a mistake,” when they saw the word “person with a felony conviction.” But 68% of respondents associated the word “felon” with negative impressions like “dangerous,” “scary,” and “serious criminal.” They saw similar trends with other words.

“Words are everything. It becomes that adjective that denies you every opportunity that people have been preparing for.”

Norris Henderson

In my conversations with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated writers, some of them told me that the word “prisoner” was acceptable to them because it literally meant “a person held against their will.” Henderson said he also found “offender” to be less offensive than the word “inmate.”

But Lawrence Bartley, the director of The Marshall Project’s News Life Inside, pointed out that the problem with that is that the preferred term among people who are impacted could be different depending on the region. “Where I was incarcerated, being called an inmate was tantamount to being called a racial slur,” he said, adding that in some Midwestern states, people prefer to be called an inmate rather than a prisoner. “It’s best to simply call people by their names.”

In instances where it’s unavoidable to describe a person’s relationship to incarceration, editors might argue that “person who is incarcerated,” or “a person behind bars,” is too much of a mouthful, but Zöe Towns, FWD.us’ senior director for criminal justice reform, argues that “the issue of word count is just a question of prioritization.”

This issue isn’t just one for editors. FWD.us had singled out The New York Times in its People First report in 2020 for using the word “convict” four times more than the next closest major newspaper, but when I looked through some articles on its site recently, I found that there were inconsistencies in terminology depending on the article, suggesting that reporters can have an impact by being thoughtful in their word choice. Most recent NYT articles that I looked through largely used person first language.

At the Prison Journalism Project, we have a dual challenge when it comes to this issue of language because we work with writers who have not necessarily put thought into how they would like to be described. In the vast majority of the stories we receive, writers refer to themselves and people inside their community as inmates, convicts, felons and prisoners. A few do it intentionally, but most do it because they’re used to being called by those labels.

“They live in an environment where this is the language,” Henderson said. “That’s all they hear… You are who you think people think you are.”

For the moment, we have published our writers’ work using the terminology that they themselves select. We intend to always respect their choice of words, but in 2022, we hope to also provide some kind of guidance, so they have the opportunity to be thoughtful in their choices and can join the effort to bring about the necessary change.