![Screenshot of information grid A grid displaying information Row 1 Column 1: Values, Goals, Mission Statement Column 2: A [orange box] Column 3: Blank Column 4: O blue box] Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 2 Column 1: Mission change Column 2: Blank Column 3: Blank Column 4: O [blue box] Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: T [Veto] [violet box] Column 7: Blank Row 3 Column 1: Organizational strategy [merger, closure] Column 2: Blank Column 3: Blank Column 4: O [blue box] Column 5: S* [green box] Column 6: S* [green box] Column 7: Blank Row 4 Column 1: Organizational strategy Column 2: A [orange box] Column 3: Blank Column 4: Blank Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 5 Column 1: Organizational needs Column 2: Blank Column 3: A [orange box] Column 4: S [green box] Column 5: Blank Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 6 Column 1: HR policies & procedures Column 2: Blank Column 3: A [orange box] Column 4: Blank Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: T [Optional] [violet box] Column 7: T [Optional] [violet box]](https://rjionline.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/08/francisgreene23083105-1024x576.png)

How to bring democracy into your newsroom

Build a power-sharing decision making model that works for you

We want journalists to ask questions, investigate, and hold the powerful to account. But in most of the newsrooms we’ve worked, management chafed if those same journalists started asking questions about their own workplace.

The moment we decided to relaunch The Appeal, we committed to building a different kind of organization—one that actually welcomes transparency and accountability. As a matter of principle, we believe that democracy is as important to a healthy newsroom as good journalism is to a healthy democracy. But more importantly, we believe that our team deserves to be part of the decisions that impact their work and their livelihood.

At most organizations, staff are traditionally left out of critical decisions, leading to feelings of powerlessness and burnout. But at The Appeal, we use a democratic decision-making framework to guide how staff participate in all aspects of our work. By creating a formal process for participating in major decisions, we balance the desire for inclusion and equity with the everyday need for efficiency and autonomy.

We often hear from journalism leaders that the way we make decisions is great, but untenable for their organization. We get it, it can feel really overwhelming. But even if you can’t implement democratic decision-making across your entire organization, the following steps will help you identify how to bring a more consensus-based, or even just consultative, approach to your teams, however big or small.

Step 1: Select (or create) a framework

There are books and dissertations a plenty on the values of democratic decision-making and the best way to go about it. You may have heard of RAPID or RACI, both of which are popular in even traditional businesses. But there are many models you can look at to see what might suit you.

For small teams, you could try RAD or DARE, while larger teams can try MOCHA. For organizations with teams that are often impacted by other people’s decisions, FINAL can be a good option. (And if you really want to rethink operations from the ground up, TEAL and Holacracy are commonly discussed.) Organizations like the Sustainable Economies Law Center are a great starting place if all of these acronyms are making you go crosseyed.

At The Appeal, we found different pieces of these models helpful, so we put them together to create our own. Our current framework is called OATS.

Why? To be honest, if you’re going to say this word over and over again, our thinking was, let’s at least make it cute.

Each letter of OATS stands for a role in executing a project or making a decision:

- Organizer: Assigns responsibility and holds the point person accountable. This is generally a member of leadership

- Accountable: Does, or oversees, the actual work

- Team Input: Staff who need to be consulted because they’ll be affected by the decision (their advice is strongly considered but not binding)

- Sign Off: The decider (At The Appeal, All Staff are frequently the S).

While some projects/ decisions may need every OATS role filled, others may not but generally, the ‘A’ and ‘S’ are always assigned.

Step 2: Decide what needs deciding

To be clear, nobody wants to, or could, have every colleague agree on every decision an organization makes—and that’s not how The Appeal operates. (Well, not anymore. In those hazy early days, by default we tried to all completely agree on every decision we were making, from our social media strategy to fundraising materials, and realized within weeks that was a recipe for disaster.)

We focus on getting our team’s input on the strategy & business side of our organization. For editorial, while we collectively discuss and decide non-urgent pitches as a team, once a story is approved our workflow looks the same as any other newsroom: Writers are assigned an editor, the two finalize drafts, drafts move through fact checking and copy editing, and then get published.

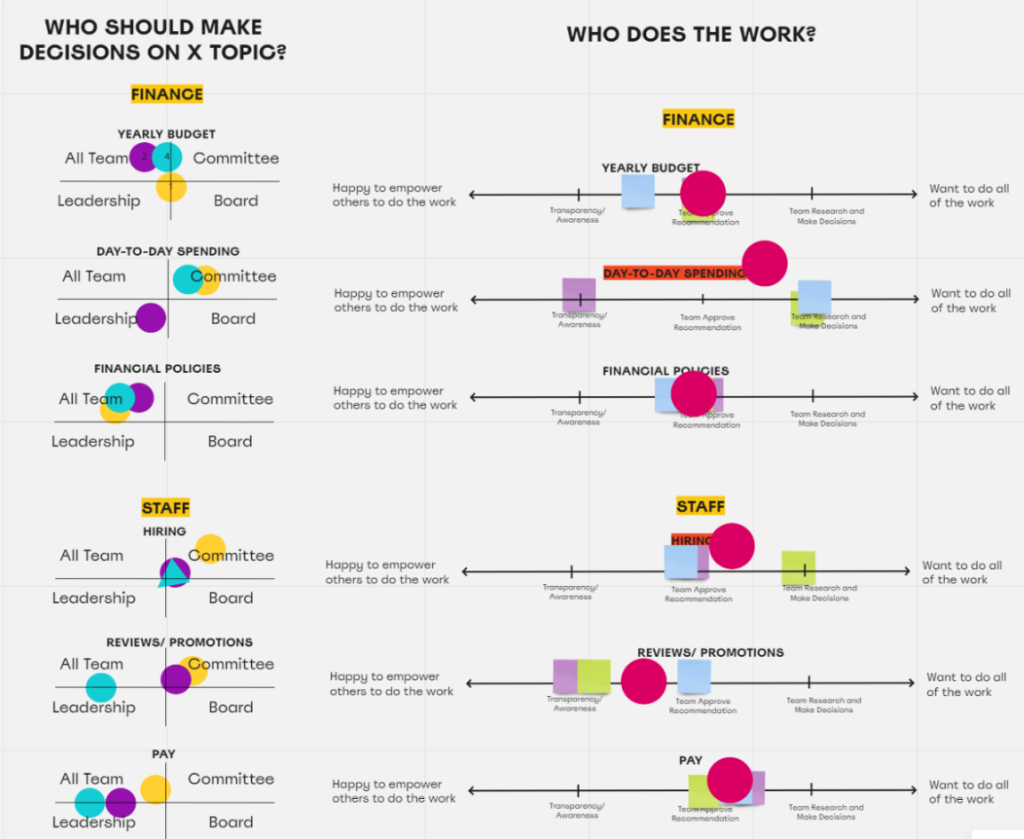

To avoid total chaos and figure out exactly what our team wanted input on, we asked them. We brainstormed critical decisions and asked, under each one, who should do the work and who should make the final decision. We found small groups were an easier way for our team to chat with each other and give input, since not everyone is comfortable sharing their thoughts with a big group.

Tools like Miro were really helpful throughout this process, since it gave our team an easy way to vote on each decision:

We broke our categories out into:

- Finance

- Staff

- Operations

- Culture

- Strategy

- Fundraising & Ad hoc

If you already lead a small team, you could break this down further such as Budget, Project Approval, Project Management, etc.

Here’s a Miro board template you can copy and use to survey your own team. (Open the Miro, go to Settings>Board>Make a copy.)

If you’re not a fan of dot voting, here are some helpful questions to ask your team, or even yourself:

- Who do you think should make X decision?

- Who should do all the research about X decision?

- Who should do the implementation of X decision?

- Do you, as a Y team member, want to do this work?

- Which of these do you, as a Y team member, want to do:

- Make the decision

- Approve a recommendation

- Be made aware of the decision

- Be left out of the decision

Step 3: Write it down

This seems obvious, but document, document, document.

Once you know what framework you want to use, write down all the decisions you went through in Step 2, and align the dot voting/answers as best you can with the roles laid out in your model.

For OATS, you can use this template.

At The Appeal, our OATS doc, which memorializes who makes which decisions and how, is kept in its own Google Doc and replicated in a How We Work guidebook for all staff.

The more visual it is, the easier it will be to use. Here’s what one section of our OATS doc looks like:

We also have an at-a-glance version, which helps give a top-line understanding of who is the decider (the OATS ‘S’) on key decisions:

Here are some other examples of graphic representation.

Even if you don’t want to change how you make decisions, documenting who makes what decisions in a chart is a really helpful tool for practicing transparency and empowering staff on your team.

Step 4: Pick an approval threshold

Once you know who decides what, you can finally figure out how the deciders will actually make a decision—a key part of the process if the decider is more than one person.

Common options are:

- Active Solidarity (the option The Appeal uses)

- 100% approval (do not recommend)

- 66% approval

- 50% +1 approval

We know it’s unlikely we’ll get an emphatic “yes” from everyone every time we need to make a decision, so the bar we use is “Active Solidarity” (shoutout to Defector Media, who we borrowed this idea from). A decision is approved when everyone listed as a decider supports a decision, even if it’s not their favorite. This is given through giving a physical or emoji thumbs up on Slack or explicitly saying or typing support in a Zoom chat.

It’s important to know what happens if a decision isn’t approved. At The Appeal, we go back and revise our recommendation based on the feedback we received, then seek Active Solidarity a second time. If it still can’t be reached, a vote for ⅔ approval is held—something we’ve never had to do in more than two years.

A small note: While most of our decisions are made with Active Solidarity, key decisions such as leadership changes, large expenses, and decisions about the organization’s future are made jointly by our staff and board of directors, so do require ⅔ approval. We’ll get more into that in a future article.

Don’t be afraid to iterate

We did not start out with OATS. Initially, we created a framework we called ‘MATCHA’. It was a good system, but it didn’t work for us. The explanation document was seven pages and it had six roles—nearly as many people as we had on staff. It was just too complicated.

So, we evolved our model by defining the fewest roles necessary, which is how we created OATS. Even now, we continue to adapt and refine OATS as new projects and new insights arise.

It becomes second nature

This process can seem overbearing, but once you do the work upfront, following your decision-making process quickly becomes second nature, and transparency and accountability becomes the default.

We should all be taking the time once and a while to check in on how we work, ask what’s working and what’s not, and adjust workflows as needed. Adapting your decision-making framework gets easier over time, and encourages you and your team to pause, reflect, and make sure things are working for everyone.

It’s been really helpful for us to have one person—in our case, Tara—ensuring we are following OATS. Over time, she’s needed to guide our team less and less, but she is still there to remind us of who’s supposed to be involved in decision-making when more complex matters come up.

This is an investment

Yes, all of this takes time. But it’s worth it.

In our experience, staff who have a voice in their organization are less stressed and more appreciative. Our team repeatedly says how much they value having input and final say on things like their own compensation, HR policies, and who gets appointed to our Board of Directors.

At the end of the day, the benefits of making decisions together far outweigh the extra time it sometimes takes to include people in decision making. In a time of journalist burnout and cynicism, bringing in democratic and power sharing models allows staff to feel heard, valued, and excited to come to work—and stay here.

As an industry, we talk so much about the financial stability of our newsrooms. But our newsrooms also need to be culturally sustainable for our teams. Not only listening to your staff, but formally including their opinions, whether that be through input or decision-making, builds trust, buy-in, and a deeper desire to make your newsroom succeed.

![Information chart Row 1 Column 1: Blank Column 2: Role Column 3: Definition Row 2 Column 1: O [blue box] Column 2: Organizer Column 3: Assigns responsibility • Holds point-person or team accountable • For projects, makes suggestions, ensures projects run smoothly, and schedules check-ins • In a committee, they facilitate meetings, set team policies, diffuse team conflicts, and make sure teams of accountable people run smoothly Row 3 Column 1: A [orange box] Column 2: Accountable Column 3: Does the work • The actual point-person or people for a project • Carry out tasks with autonomy, but must report back to the Organizer as needed • After a decision is made by the Sign-off, usually takes required action Row 4 Column 1: T [violet box] Column 2: Team input Column 3: Is consulted • Team members who need to be consulted during a project or decision • Input must be strongly considered and taken into account by Sign-off but can be ignored Row 5 Column 1: S [green box] Column 2: Sign-off Column 3: Decides or signs off recommendations • The decision-maker/s, responsible for making decisions • Responsible for ensuring that all perspectives have been heard and , if relevant, consensus is clerly met](https://rjionline.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/08/francisgreene23083102.png)

![Screenshot of a chart titled "Strategy & Operations" Row 1 Column 1: Key decisions Column 2: Strategy & Legal dir. Column 3: Managing ed & Ops dir. Column 4: Leadership Column 5: Staff collective Column 6: Board of directors Column 7: External Row 2 Column 1: Values, Goals, Mission Statement Column 2: A [orange box] Column 3: Blank Column. 4: O [blue box] Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 3 Column 1: Mission change Column 2: Blank Column 3: Blank Column 4: O [blue box] Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: T [veto] [violet box] Column 7: Blank Row 4 Column 1: Organizational change [merger, closure] Column 2: Blank Column 3: Blank Column 4: O [blue box] Column 5: S* [green box] Column 6: S* [green box] Row 5 Column 1: Organization strategy Column 2: A [orange box] Column 3: Blank Column 4: Blank Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 6 Column 1: Organizational needs Column 2: Blank Column 3: A [orange box] Column 4: S [green box] Column 5: Blank Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 7 Column 1: HR policies & procedures Column 2: Blank Column 3: A [orange box] Column 4: Blank Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: T [Optional] [violet box] Column 7: T [Optional] [violet box] Row 8 Column 1: Updating OATS Column 2: Blank Column 3: A [orange box] Column 4: Blank Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 9 Column 1: Legal issues Column 2: A [orange box] Column 3: Blank Column 4: S [green box] Column 5: Blank Column 6: Blank Column 7: T [Mill Law, Smarter Good] [violet box] Row 10 Column 1: Partnerships Column. 2: A [orange box] Column 3: Blank Column 4: Blank Column 5: Blank Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 11 Column 1: New committee Column 2: Blank Column 3: Blank Column 4: Blank Column 5: S [green box] Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 12 Column 1: Contractors Column 2: Blank Column 3: Blank Column 4: O [blue box], S [green box] Column 5: T [Transparency] [violet box] Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank Row 13 Column 1: Vendors Column 2: Blank Column 3: A [orange box] Column 4: O [blue box], S [green box] Column 5: T [Transparency] [violet box] Column 6: Blank Column 7: Blank S*: Requires 2/3 full organizational vote with the Staff Collective and Board of Directors at separate meetings.](https://rjionline.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/08/francisgreene23083106.png)

![Chart consisting of a series of nested circles, each circle labeled. From the outside in: Circle 1: Board of Directors • Existential governance • Legal governance • Leadership accountability Circle 2: Leadership • Strategic implementation • Staff support & accountability Circle 3: Staff • Existential governance • Leadership & BOD accountability • Team culture [policies, compensation, benefits] • Financial direction [budget] Circle 4: Committees • Editorial • Newsletter • Budget • Development](/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/08/francisgreene23083101-948x1024.png)