The candidate forum started with multiple listening sessions where six to eight voters discussed the issues most important to them and what they were looking for in a candidate.

How we aimed to center community voices in a candidate forum

A collaborative take on election debates

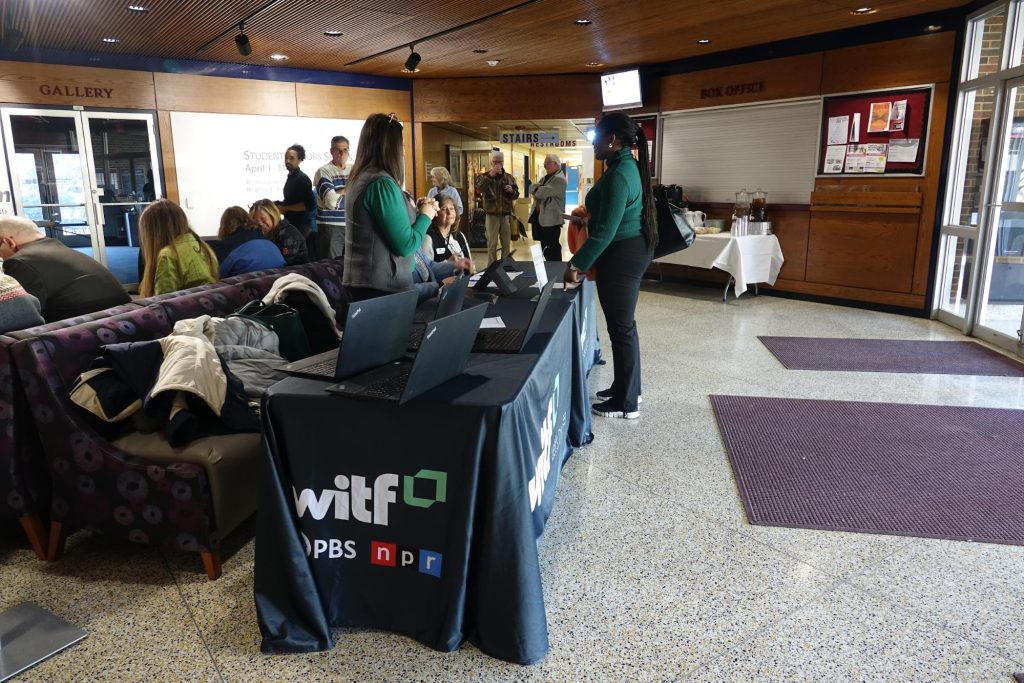

WITF, York Dispatch,York Daily Record and PennLive/Patriot News, a cohort of central Pennsylvania newsrooms, worked with Innovation in Focus to host a new kind of candidate forum. The idea was to flip the script: Instead of starting onstage with the traditional panel format, the candidates began the night by listening to community members in small group listening sessions. They were asked to stay silent during the listening sessions and allow the attendees to set the agenda for the later moderated conversation.

We wanted to make this interactive for the participants but still informative as they prepared to head to the polls. While we learned lessons on how we might increase interactivity in the future, several participants told us that this felt different and more engaging than previous election forums. We also gave everyone the opportunity to mingle and address candidates directly after the event.

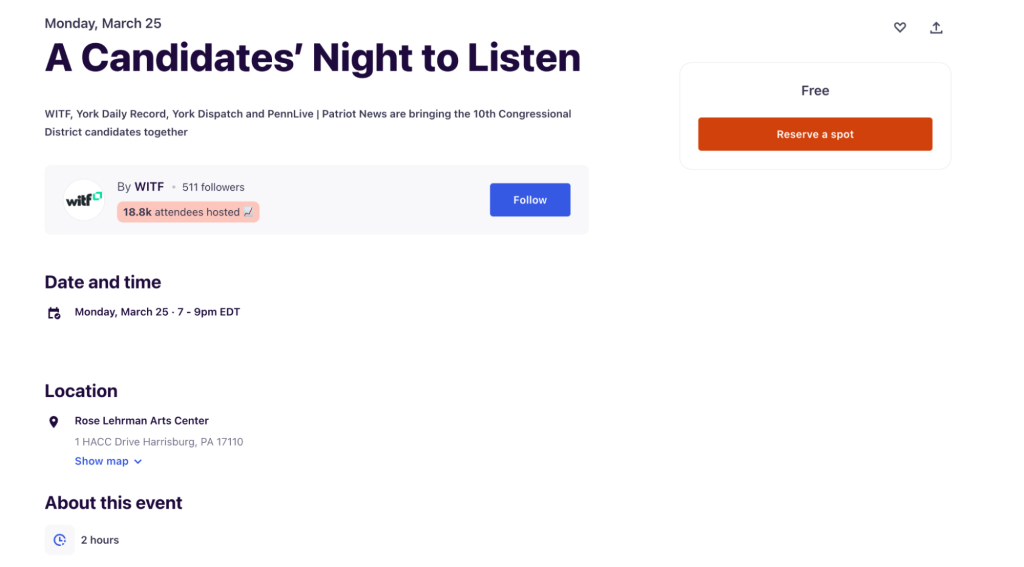

Nearly 200 people attended the Candidates’ Night to Listen on Monday, March 25 ahead of the April primaries. Staff from all the newsrooms involved helped organize the event and facilitated listening sessions. Several community participants commented that they appreciated this collaboration.

Want to build your own election listening event? Here’s how we did it:

First steps: venue, candidate communications

We met with representatives from each newsroom in weekly meetings on Teams starting in January. All organizers agreed that they wished they would’ve started these planning meetings sooner, but the weekly check-ins added a helpful level of accountability.

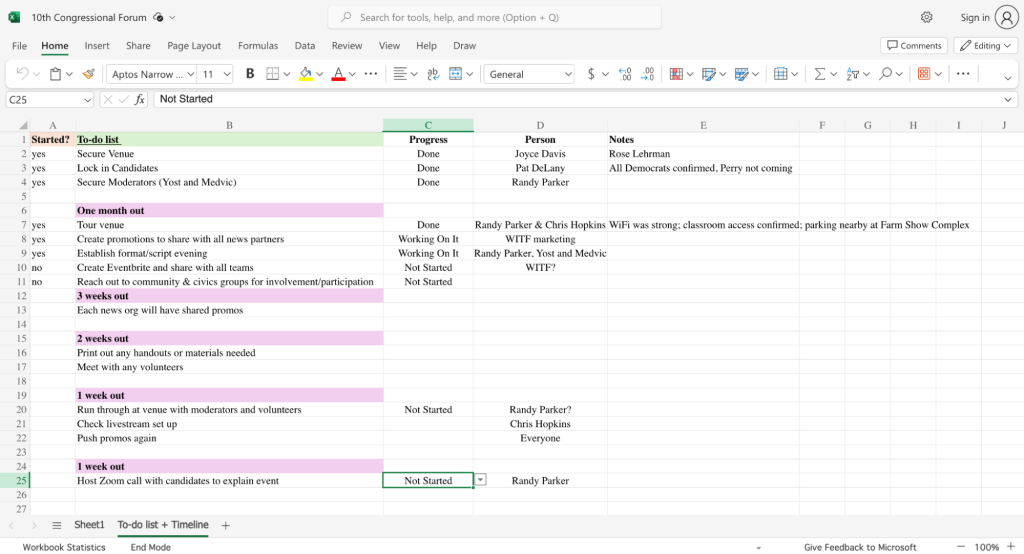

The first few items on our to-do list included:

- Identify and confirm a venue — and ideally one that will host for free

- Invite all candidates and confirm their attendance

- Find and confirm a nonpartisan moderator (or two)

- Confirm a date that is reasonable for planning but close enough to the primary

Randy Parker, news director at WITF, worked as the project lead and created a spreadsheet with all these initial tasks. He asked one person from the group to take ownership over each item.

WITF’s events team joined the planning process in February. This team included: marketing, the multimedia production manager, who made sure the audio and slideshow/presentation pieces are all set and the volunteer coordinator, who brought in and organized six community volunteers. The volunteers helped greet people, give directions, hand out surveys and more.

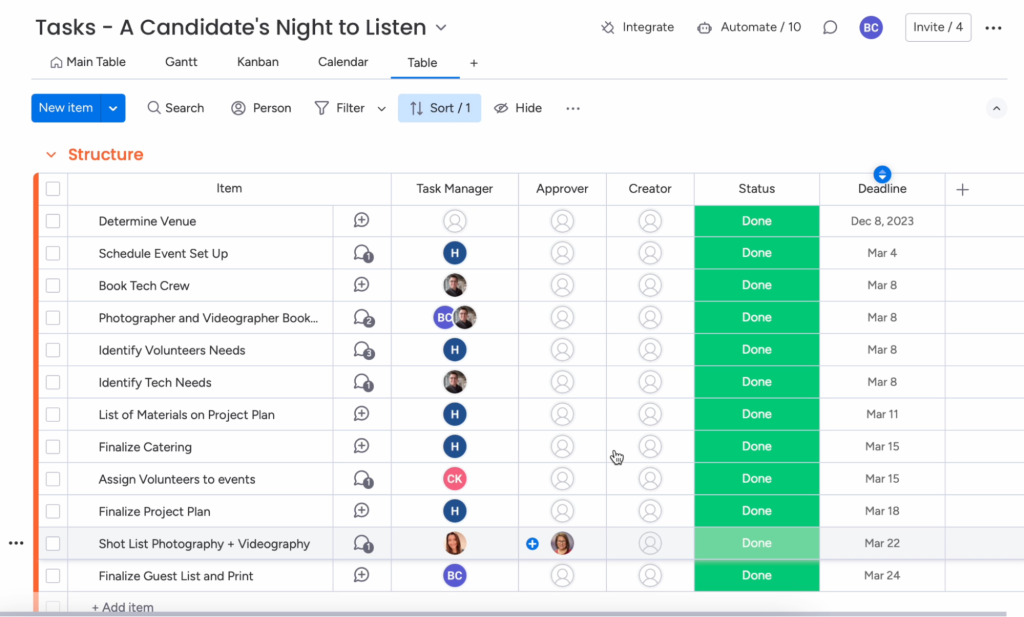

The WITF marketing team created a partner toolkit with shared images and messaging, which included all four newsrooms’ logos, so each organization could post the same content on social media, websites, newsletters and radio spots. To organize and assign all of these tasks, the team used the project management tool Monday.com.

While Beth Cappello, WITF’s project manager, said they were happy with the turnout in such a short window of promotion, they would have liked to dedicate more time and marketing dollars to broadening their reach and bringing in a more diverse audience. To do this next time, they hope to partner with community organizations, rethink the location of the event and provide childcare for families.

Innovating the format

By far, the most challenging part of the planning process was settling on a non-traditional format. We considered multiple options, which we organized in a brainstorming doc so that we could see all our ideas in one place.

To anchor our ideas, we established a goal: Help present to the candidates what the community needs from their representative in Congress. But also help the community understand how their needs align with the candidates to help them decide who to vote for.

One idea that we implemented was to give the audience members the opportunity to interact with one another and share a little about themselves. Jennifer Brandel, co-founder and CEO of Hearken, had a few good suggestions on how to do this, such as:

- Give a sense of who is in the room. Ask people to raise their hand or stand up if a statement applies to them. You can get more personal as you go.

- For example: Raise your hand if you live in York County. Raise your hand if you identify as liberal/conservative/moderate, etc. Raise your hand if there are issues in your political party that you don’t fully agree with.

- Give people a chance to reflect with each other at the end of the event. For example, “turn to someone around you and share one thing you learned or one thing you shifted your position on.”

We ultimately tried the first option where the moderators asked people to raise their hands based on where they lived, how they identified politically and how old they were. While WiFi issues prevented us from using the tool Poll Everywhere — which allows participants to text their answers and display them on a screen on stage — as planned, we hope to use it for more interactivity in the future.

This first question also gave the organizers a good idea of how diverse our participants were. For example, only a couple of people raised their hands as being under the age of 30, and most participants identified as “liberal,” which wasn’t surprising since the only Republican candidate did not attend.

The most innovative piece of the format was the community listening sessions. Once we confirmed and visited the venue, which included several classrooms on the second floor, we were able to envision splitting community members into more intimate listening groups with candidates.

To keep the focus on the community and center their voices, each classroom had a candidate present, but that candidate was not allowed to participate or speak. (And most candidates did a pretty good job at this!)

The listening sessions

Since these listening sessions needed to be small enough to foster thoughtful conversations, we limited each classroom to no more than eight community members. When people registered for the event on Eventbrite, they had the option to volunteer to participate in one of these pre-event sessions. Once we hit max capacity of 60 people, we removed this option from Eventbrite.

In each classroom, one facilitator led the conversation and kept time, and one person took notes in a shared Google Doc with all the other classrooms. Each classroom also included one candidate who generally sat in the back of the room or in a side corner. We placed them this way so that they were not tempted to join the conversation, but we found people were still tempted to turn in their seats and address the candidates.

Here is the script we used to lead these conversations: Classroom Script Template.

The 30-minute discussions went very quickly, and in our debrief we talked about adding more time in the future.

One more important note: Finding a local partner like Franklin & Marshall College was critical when designing the script and then translating the classroom notes into meaningful questions for the candidates. Our two F&M moderators, Berwood Yost and Stephen Medvic, brought expertise in qualitative research that helped take our community journalism to a deeper level.

The main event

The mainstage part of the night was open to everyone, and the moderators used the classroom discussions to drive their questions to the candidates for the main room event.

A few participants said they noticed that the questions connected back to those earlier conversations, and they said they appreciated the thoughtfulness. For the moderators, though, this was a mad dash to compile all the notes from the individual classrooms and integrate them into questions for the panel.

One thing that would have made this easier is to establish a set format for the note-takers. For example, it may have helped if everyone agreed to write their notes in a different color and summarize the key takeaways at the top. The moderators also suggested using an AI transcription service or something similar to have a more complete transcript they can search later.

Several people said they appreciated the first question asked of the candidates:

What did you hear in your classrooms?

This allowed the candidates to respond and reflect on what the voters told them, often directly addressing concerns that participants raised.

While the moderators attempted to keep the rest of the evening conversational, it eventually fell into the traditional tossing-back-and-forth of talking points by the candidates. One suggestion from a participant was to set the candidates up in a fishbowl format or sitting in the audience to avoid this habit.

Two other ideas for involving the audience more:

- Ask a couple of voters from the classroom session to report back and share their takeaways or questions.

- Use Poll Everywhere or similar technology to allow audience members to answer and ask questions during the mainstage forum.

Post-event

After the mainstage forum, we asked the candidates to return to their originally assigned classrooms. Then, community members were able to go ask direct questions of the candidates after hearing them talk on stage.

Several people took advantage of this opportunity and talked with candidates for more than 30 minutes. Participants told us they appreciated this portion of the event. We were also impressed that people took the time to talk to a variety of candidates by visiting multiple classrooms.

A small logistical note: Make sure the candidates have time to reach the classrooms before connecting with people in the crowd. They will get distracted.

Interested in learning more about hosting community-centered events? Join our online conversation with panelists on Friday, May 31 at 11 a.m. Central Time. Register here: bit.ly/CommunityEventsPanel.

Sign up for the Innovation in Focus Newsletter to get our articles, tips, guides and more in your inbox each month!

Cite this article

Lytle, Emily (2024, May 6). How we aimed to center community voices in a candidate forum. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/how-we-aimed-to-center-community-voices-in-a-candidate-forum/

Comments