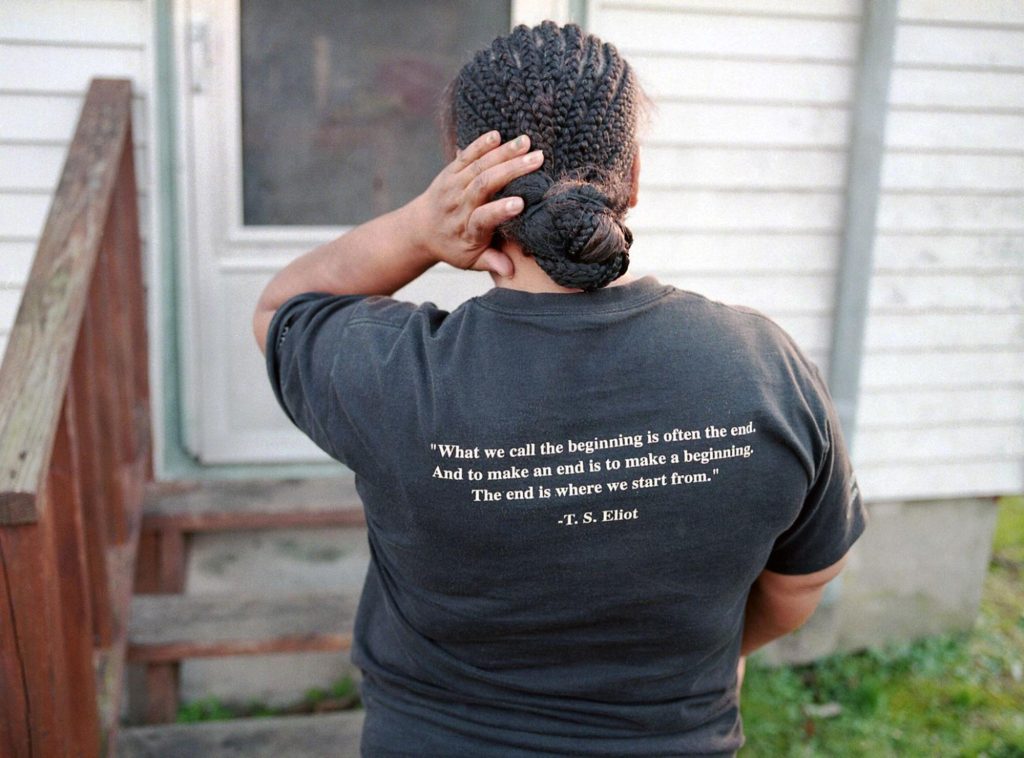

Nelson in South Carolina, photographed by Sarah Blesener from “How the Young Return”

Listening, loss and what we might miss (and learn) from each other

Co-creating care-driven resources for visual journalism

With the support of the Reynolds Journalism Institute, we are designing an evolving resource for visual journalists and newsrooms that prioritizes survivor-conscious and responsible approaches to sensitive stories. We believe these collaborative ways of working ultimately lead to more ethical and compassionate storytelling. Together we hope to work with freelancers, staff photojournalists, editors, educators and newsroom leaders to help create safer spaces for both participants and journalists.

Enter/Exit will offer an open source collection of perspectives, interviews, essays, poetry, photographs, shared experiences, artwork, and pedagogy, with the intention of being in service of taking better care of both participant and practitioner, serving as a conversation starter for industry professionals, and a space for fostering community.

We will break down the process of entering and exiting a space in the aftermath of trauma, from collaboration, to creation, to exit, emphasizing the importance of ongoing dialogue and sensitivity.

How we got here

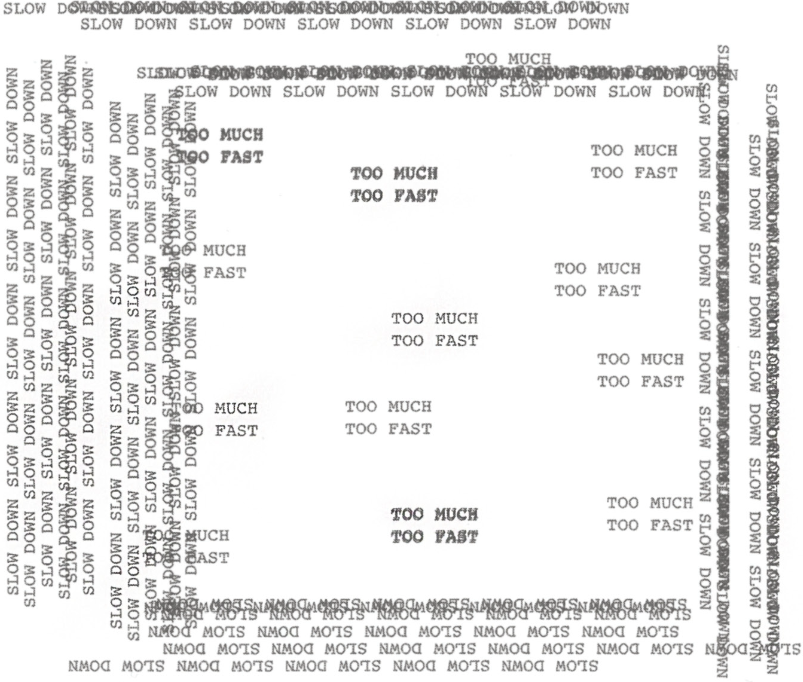

“Too much, too fast”

A common definition of trauma has been “too much, too fast.”

More often than not, “too much, too fast” is the foundational basis of how contemporary journalism is conducted, where there is a pervasive tendency to prioritize speed and quantity over sensitivity and depth. This approach, when applied to traumatic stories, not only risks desensitizing audiences but also has the potential to be destabilizing and triggering for those directly involved. Often this is even more pronounced in visual storytelling.

Is it possible for the entire process of storytelling and image making to be cathartic, empowering or even healing for those involved? Can we challenge conventional storytelling approaches to foster narratives that are sensitive, nuanced, and visually complex?

Living the questions

“I read somewhere that there is a music that only the grieving can know because they chose to carry on. You may not believe me now, but one day you will wake up, and without warning, you will start hearing that music. You can’t look for it, you can’t force it. But it’s there. And you will hear it.” — G.A reflects during a grief support group

Last year, we found ourselves flipping through our old journals used over the years to process emotions and experiences after photographing intense, often traumatic stories. In one such notebook, nestled between field notes, was a moving personal reflection from someone Sarah photographed about moving through a deep grief and loss.

Their words weren’t about what had broken them, but what had kept them going. What helped them breathe. Rise. Keep moving.

Looking back at those notes, something shifted. A realization surfaced: somewhere along the way, we had forgotten to look to the people who truly understand what it means to survive, not just in the moment of the story, but long after it fades from public view.

We began asking ourselves some hard questions:

- What else have we been missing?

- What was actually helping in all of this, in our approach? What was causing harm or could have gone better? How will we know if we don’t follow up, if we don’t ask how it felt to be photographed, interviewed, to have your image and story publicly presented?

- What resources and structures are needed to support process-driven, rather than product-driven, visual journalism?

These shared questions led Sarah to reach out to someone they had photographed the year before, and that exchange sparked something deeper: a reckoning with our own practices.

Together we partnered with L.J. Granered, a practitioner of somatic trauma integration whose vocabulary for safety is from a lens of lived experience and recovery, as well as a participant behind the camera telling their own story. Our work led to more outreach, reflection and eventually conversations with over 40 individuals who generously shared their insights and experiences of being photographed or interviewed in the aftermath of trauma — feedback that, in our experience, often does not make it back into the newsroom.

These conversations have become the foundation of our collaboration in developing an open-source, digital resource for trauma-informed visual journalism, grounded in listening, accountability, and the belief that how we tell and co-create stories matters as much as the stories themselves. Our project will question, reflect, and gather resources for alternative ways of working in visual journalism, especially by listening to and learning from people outside the journalism field. This includes trauma therapists, social workers, researchers, survivors, and artists.

As visual journalists, the interactions we have with people leave imprints that last long after the time we share together. Those imprints should shape the process of this work too. Enter/Exit aims to center the knowledge of survivors as well as will include strategies and exercises developed through interviews with artists, therapists, editors, and others who have supported journalists or photographers working with trauma survivors.

Topics will include:

- informed consent

- preparing for sensitive stories

- collaborating with participants

- anonymous portraiture

- trauma and body language

- aftercare practices

- newsroom frameworks

As journalism becomes more visual and increasingly influenced by new AI-driven technologies, understanding the ethical implications of image-making is more critical than ever. Amid challenges like sensationalism, the erosion of public trust and rapidly changing technology, Enter/Exit offers a vision for ethical, sustainable reporting — particularly in the high-pressure and emotionally taxing field of visual journalism, where the pace and workload can feel relentless. We move from one assignment to the next, often without pause.

But if we’re serious about honoring the people who allow us into their lives, shouldn’t we be asking them what their experience was like? What went right? What could have gone better? What impact did it have? What do they see in the photographs? What critiques or reflections might they share?

An open invitation

As we re-imagine what visual journalism can look and feel like, we invite you to reflect on your personal and professional experiences:

- What did you love making with your hands as a child — drawing, building, braiding, piecing things together?

- When you were going through something hard, what gesture or question made you feel genuinely supported?

- In a world that often feels like “too much, too fast,” how might we slow down and bring that same creativity or care into journalism?

If you would like to share your reflections, questions or connect please get in touch with us here.

Cite this article

Jacklin-Stratton, Jennifer; and Blesener, Sarah (2025, July 28). Listening, loss and what we might miss (and learn) from each other. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/listening-loss-and-what-we-might-miss-and-learn-from-each-other/