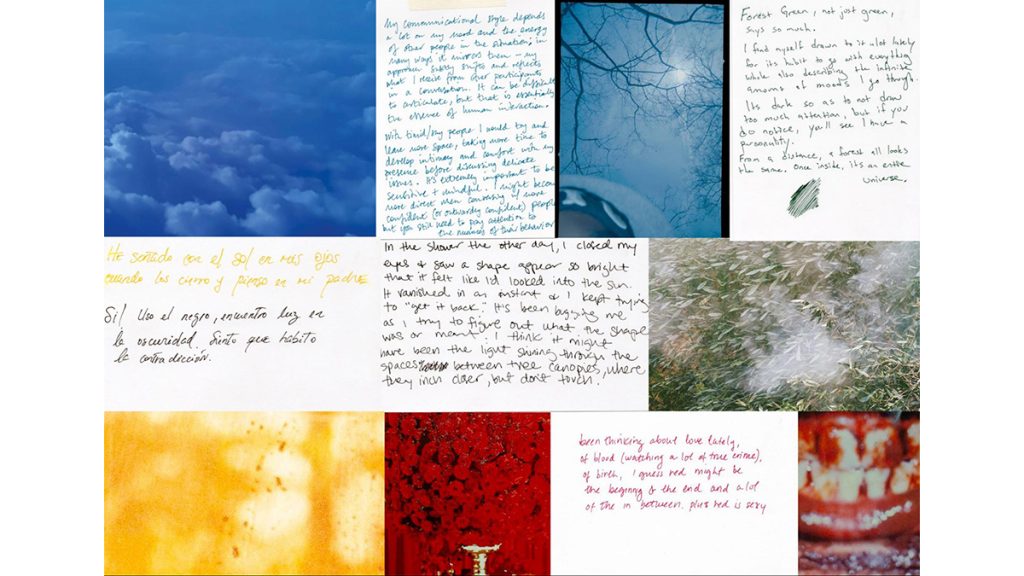

A mosaic of color studies/responses by attendees at the Enter/Exit community event at Plena Productions. Photos: Sarah Blesener and Jenny Jacklin Stratton

Participatory ways of working

Practices of play, trust and collaboration

To notice color is to listen: to what soothes, what unsettles, what echoes through the body like a remembered room.

Studies suggest that color affects the nervous system: certain hues can regulate heart rate, trigger memories, or stir emotional responses rooted in past experiences. Researchers Elliot and Maier note, “Color carries meaning, and this meaning can exert a significant influence on psychological functioning,” not in isolation, but in context, shaped by personal and cultural experiences of color perception. As artists, practitioners and storytellers, this awareness of how color interacts with the body and mind help us to begin to use color thoughtfully, intentionally and with care in image making.

Color can mark the quiet maps of our inner worlds. In visual storytelling, color is not decoration but language. It speaks in warmth and distance, urgency and calm. A carmine thread may hold the weight of anger; a pale blue, the breath of relief.

Prompt:

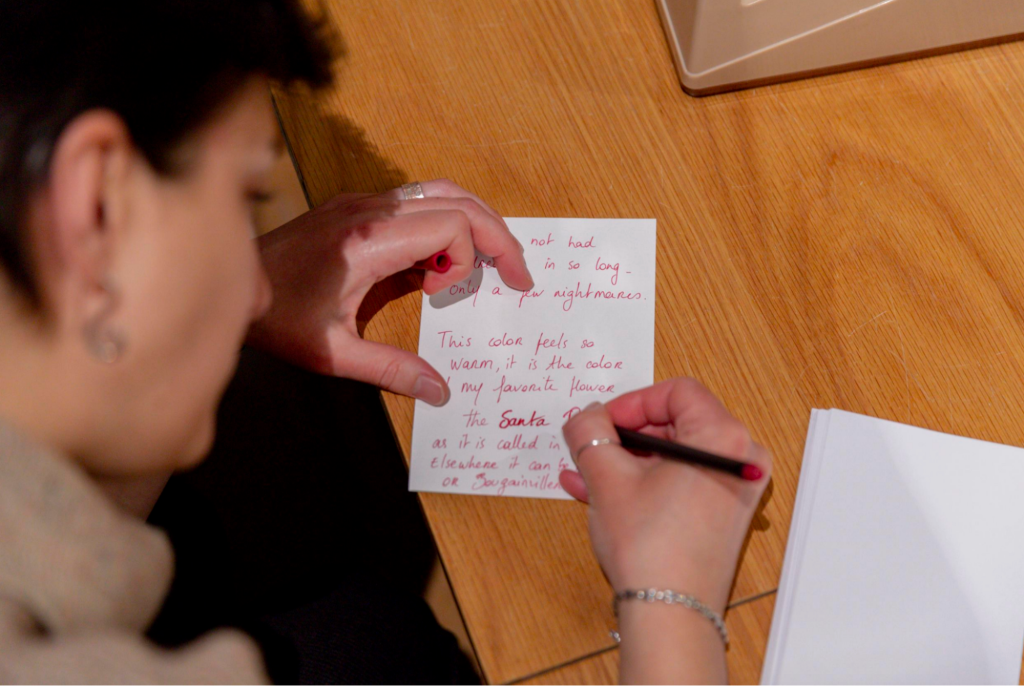

Choose a color that has been affecting you lately and describe it. Do you dream about it, dress yourself in it? What does it make you feel? Is it attached to any memories or emotions? Write a reflection in a marker or pen with ink that most closely matches that color. Then take notice when that color appears in the spaces around you; spend time photographing it.

Opening up collaborative work

Moving from an understanding that collaboration must start with shared decision making and transparency around time, place, boundaries, and the editorial process, we can begin to think of how to work collaboratively in our creative practice as well.

Participatory ways of working play a crucial role in deepening collaboration, generating diverse visual approaches, and fostering a sense of safety. These approaches can be especially productive when working on “anonymous” portraiture or engaging in a more conceptual approach to a traumatic story.

To start with, discussion prompts help to open a conversation and to begin a collaborative approach of visualizing the story. Sharing decision making can simply start with talking together, both in the newsroom and between photographers and participants, about how individuals would like to be seen and represented, and what colors, mood, and atmospheric elements play into these ideas:

How do you want to be represented? What do you hope others feel when they see these images we make together?

Before we start photographing together, can you try to describe how grief/hope/healing feel to you at this moment? Can you describe it in a shape, a color, a texture, a sound?

Do you have images or objects that feel important to this story? Would you like to include them in our work together?

What spaces feel safe, sacred or important to you? Would you want to photograph in any of those places?

Would you like to try experimenting with collage and writing alongside the images?

In practice

S: How do you find intimacy when you photograph your own community? What does working together feel like?

R: I think those sweet, intimate moments can only be found in moments that are actually tender. There is always that expected image, repeated over and over for stories around trauma. It still communicates, but there is not much beyond the surface. I think something deeper comes with physical intimacy, it comes with someone letting you in with trust, it comes with paying attention to the small details. What matters are the people themselves who have looked this trauma in the eye, and who need to process their experience as well. I witnessed the media swarm my town after what happened, happened. I saw many approaches. I began to photograph my own community, the grief and pain of myself and my own neighbors. I learned what emerges from moving slowly, from listening, from looking away from the spectacle, from holding hands with other people.

Rather than positioning journalists as sole authorities, we can embrace ways of working that center on care and collaboration. We can choose to ground our work in listening, learning, and exploring together, valuing everyone’s input and recognizing that each person has something important to contribute. It’s not just about disseminating information; it’s about meeting people where they are, having conversations, and learning together. It’s about building trust and safety with individuals and communities who have had their personal trust, as well as their trust in journalism, compromised.

Invitation

- What does collaboration mean to me, and how do I practice and /or embody it?

- Does our team ask for and take guidance from participants for visual and narrative directions?

- Where in our process do we still assume control rather than share it?

- How are we involving participants in the creative direction or editorial decisions, if at all?

- Do our visual patterns reflect the expected narrative tropes of trauma? What might we try instead?

Cite this article

Jacklin-Stratton, Jennifer; and Blesener, Sarah (2026, Jan. 6). Participatory ways of working. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/participatory-ways-of-working/