Photo: Graham MacIndoe

Resisting false binaries when reporting on the complexities of addiction

What’s in between forcing people into treatment and waiting for them to be ready?

Media coverage of the challenge of engaging people in care for addictions tends to present two options: voluntary vs. involuntary treatment.

This framing may reflect the polarization of the current political climate, or debates over how communities should help people with complex needs, particularly individuals navigating substance use disorders, mental illness, and homelessness.

But focusing on this either/or scenario falls into the trap known as a “false binary” or “false dichotomy:” when two mutually exclusive choices are presented as the only options, ignoring other things that exist between two extremes. It’s also frustrating for readers who are tired of polarized debates that don’t offer realistic solutions.

So what’s in between forcing people into treatment and waiting for them to choose to get help for a drug or alcohol problem—both of which have many downsides? Lots of things that happen all the time in public health, health care, and other areas of our lives, like nudging, encouraging, motivating, incentivizing, and facilitating some type of behavior change.

For people struggling with addictions, it’s usually some combination of carrots and sticks, arguably better framed as incentives and consequences, that prompt a call to a treatment provider or accepting someone’s help. It might be a pregnancy, a partner deciding they’ve had enough, a potential job loss, a health scare, an overdose, an arrest, or a trusted confidante whose advice clicks at a critical time. It may be many of these things overlapping that finally tips the scale.

The risks of waiting for people to be ready

Opponents of involuntary treatment make a persuasive case for the legal, humanitarian, and practical problems with this approach—how civil commitment decisions are made, what rights people have to appeal, where they’re sent, what treatment is offered, what capacity communities have to deliver quality care, and many other thorny questions.

But there are also many downsides to waiting for someone to be ready, including the risk of a fatal overdose and the health, social, legal, and personal problems that accumulate and become tougher to address after many years of active addiction.

Simply arguing that treatment should be voluntarily chosen overlooks the fact that a key criteria for a substance use disorder is loss of control over drug or alcohol use. Cognitive changes that impair decision-making and rewire the brain’s reward system, particularly with a more severe SUD, mean many people may never choose to get help.

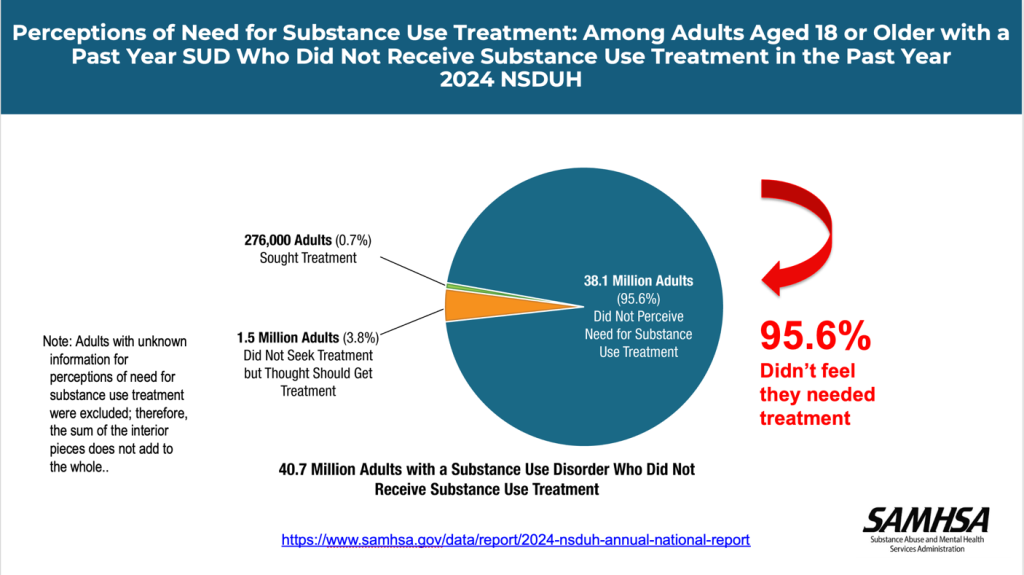

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a nationally representative annual survey, consistently reports a statistic that highlights a stark finding. In 2024, among people 18 and older who met the criteria for a substance use disorder in the past year and didn’t receive treatment, nearly 96% said they did not feel they needed treatment. That’s more than 38 million people.

For those with a mild substance use disorder—56% of those with an SUD—it’s possible that they view “treatment” as an inpatient or residential program and feel that’s not appropriate for their situation. Research consistently shows that many people do resolve a problem with alcohol or drugs without specialized treatment, which may be more common with mild SUDs.

But that’s still a lot of people who would typically be described as “in denial” about a problem.

According to the 2024 NSDUH, among adults aged 18 or older with a past year SUD who did perceive a need for treatment and didn’t get help, the following were common reasons for not receiving substance use treatment:

- Thinking they should have been able to handle their alcohol or drug use on their own (75.5%)

- Not being ready to start treatment (65.0%)

- Not being ready to stop or cut back on using alcohol or drugs (59.5%)

- Thinking that treatment would cost too much (45.3%)

- Being worried about what people would think or say if they got treatment (43.2%)

- Not having enough time for treatment (41.3%)

- Not knowing how or where to get treatment (38.9%)

- Not being able to find a treatment program or healthcare professional they wanted to go to (35.8%)

- Thinking bad things would happen if people knew they were in treatment, such as losing their job, home, or children (34.4%)

- Being worried that information would not be kept private (33.0%)

- Not having health insurance coverage for treatment (32.4%)

Many of these reasons are things policy makers and providers can address; they’re also good topics for reporters to cover. For instance, what are the best tools to find affordable, quality treatment and other substance use services, besides the federal site FindTreatment.gov? Is there a state or local treatment finder or phone service that helps individuals and families explore options—and importantly, navigate getting treatment covered by insurance?

Increasing treatment uptake and retention

There are also many approaches that exist in that middle ground between “forcing” and “waiting” that illustrate how nudging, encouraging, and facilitating treatment engagement can work. Here are some examples that offer different angles for reporting projects:

Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): Based on the idea that early intervention is preferable, SBIRT refers to a short screening process to assess someone’s substance use, having a conversation about their risks and goals, and if needed, referring them to treatment. It can be offered in primary care, health clinics, emergency rooms, and other settings. How well it’s implemented, e.g. by primary care doctors, is an important question. Do healthcare providers know where to send patients locally for addiction counseling and specialized care?

Peer Support Services: Although SAMHSA’s site describes peers as supporting individuals in recovery, in reality they work in many settings, including harm reduction organizations and hospital emergency departments. Peers typically have both personal experience with addiction and recovery as well as professional training and offer support to help others achieve their goals. Certification requirements (including across state lines), compensation, and reimbursement processes are key topics in the field.

Motivational Interviewing: Also referred to as MI, motivational interviewing is a collaborative conversational approach to strengthen a person’s own motivation and commitment to change. It’s a technique that addresses the challenge of people’s ambivalence toward change, which can be used for brief encounters in different settings by people working in a wide range of helping professions. SAMHA’s advisory about MI offers more information about how it works, research references, and places to get training. For local journalists, where can people find providers who use MI techniques—or get trained themselves? For individuals struggling with a loved one’s addiction, it can be a helpful tool.

Contingency Management (CM): This is a type of therapy that offers incentives to participants who meet a treatment goal, using positive reinforcement to motivate behavior change. Typically used as a treatment for stimulant use disorders, participants are tested for stimulants like cocaine or methamphetamine on a regular basis and immediately rewarded with a small incentive like a gift card or prize if their test is negative. A test indicating stimulant use doesn’t result in punishment; it means the incentive is not offered. California has been testing CM through a statewide trial; it is also used by the Dept. of Veterans Affairs. Barriers to implementing CM more widely are an ongoing challenge, but are important to cover as stimulants contribute to more overdose deaths.

Deflection: Unlike diversion, which typically offers treatment as an alternative after an arrest, deflection offers police officers an option to connect someone with treatment and community-based services instead of arresting and charging them. The Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative (PTACC) and the Police Assisted Addiction & Recovery Initiative offer more information about deflection practices, examples of where programs have been implemented, and lessons learned in the past 10 years.

Besides encouraging and motivating people to get treatment, there are also efforts to embrace a low-barrier approach to care by removing the hurdles people often have to overcome just to get into programs. That can include helping someone enroll in or navigate insurance coverage, appeal denials, or even replace lost IDs that are necessary to begin the paperwork process.

Thinking about alternatives to forcing and waiting, an essay titled Nudges from the Edge of Health, by Lori Melichar, a senior director at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, outlines key questions to ask:

- Who do we nudge?

- When do we nudge?

- What do we nudge?

- Where do we nudge?

- How do we nudge?

- Why do we nudge?

As an approach, nudging can also be useful when interviewing sources who focus on extreme positions. Resisting false binaries even while covering news about polarizing proposals will resonate with readers who live and work in the reality of the messy middle ground.

To sign up for email alerts when these monthly articles are published or offer feedback about the Covering Drugs toolkit I’m developing, you can fill out this form or click the link below. I’m especially interested in finding out what questions or topics journalists would like to see included, including challenges reporters have encountered finding information or data. I also welcome suggestions from researchers, service providers, policymakers, advocates, and people personally impacted by substance use and addiction.

Cite this article

Stellin, Susan (2025, Dec. 15). Resisting false binaries when reporting on the complexities of addiction. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/resisting-false-binaries-when-reporting-on-the-complexities-of-addiction/