Understanding the difference between substance use disorders and addiction

The distinction is important, but sometimes gets blurred in media coverage

Most people have an understanding of addiction, even if use of that word isn’t always precise. It’s used to describe not just problems with alcohol and other drugs, but behaviors like compulsive gambling, internet use, gaming or jokes about things like eating habits, e.g. “I’m addicted to Flaming Hot Cheetos.”

But within academic, treatment and policy circles, there has been a shift to using “substance use disorders” instead. Last year, a colleague sent me feedback about a presentation I was developing, they said “We do not use the word ‘addiction’ when we are talking about substance use disorders due to the stigma related to it.” The email referred me to a stigma glossary published by an organization with the word “addiction” in its name.

I wrote back clarifying that this glossary and others typically discourage use of the word “addict,” as part of an effort to promote use of terms that don’t define someone primarily based on their substance use. Addiction is still used by the general public as well as many healthcare providers, researchers, policymakers, and advocates.

But “substance use disorder” and “addiction” are not interchangeable.

Addiction — which the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) describes as “a chronic disease characterized by drug seeking and use that is compulsive, or difficult to control, despite harmful consequences” — correlates with a severe substance use disorder, not one that is moderate or mild.

That distinction sometimes gets lost in media coverage of drug and alcohol problems, but it’s important to understand.

How are substance use disorders defined?

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), “Substance use disorders occur when the recurrent use of alcohol and/or drugs causes clinically significant impairment, including health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home.”

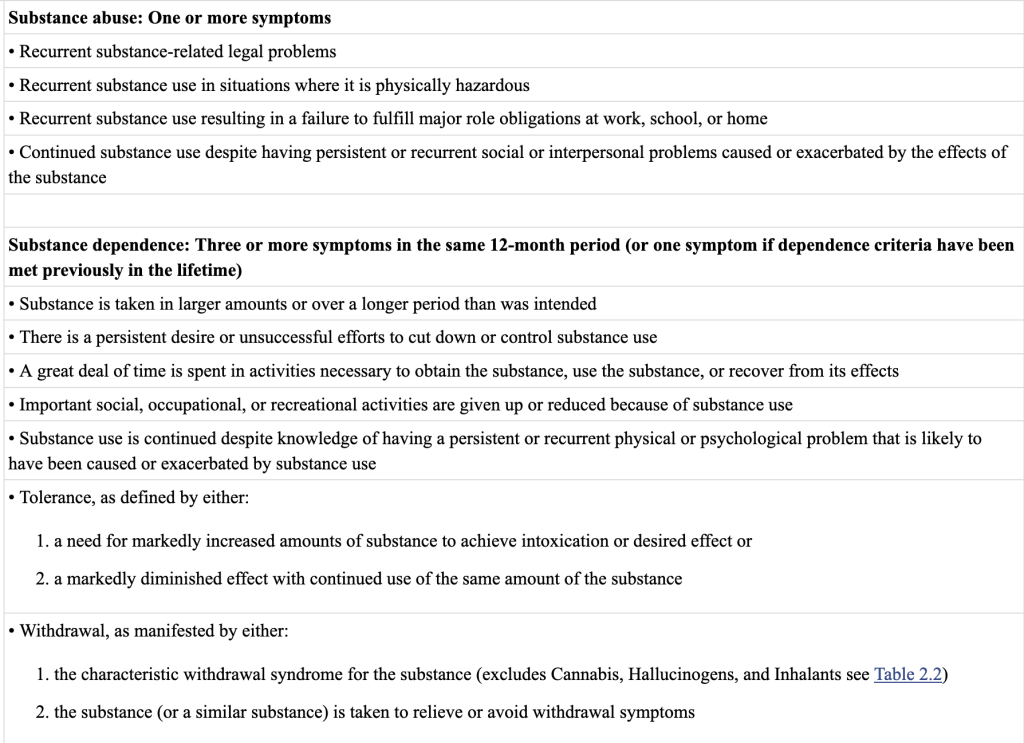

There are 11 criteria used to determine if someone has a substance use disorder, based on the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) published by the American Psychiatric Association. The criteria are sometimes grouped into four categories, which capture the impact of drinking or drug use on someone’s life.

Criteria for a substance use disorder

Loss of control

- Using a larger amount of a substance or using it more frequently than intended.

- Trying to stop or cut back and not being able to control substance use.

- Spending a lot of time obtaining or using a substance, or recovering from its effects.

- Experiencing a strong desire or craving to use a substance.

Interpersonal consequences

- Failing to fulfill major obligations at work, school, or home due to substance use.

- Continued use despite it causing significant social or interpersonal problems.

- Skipping social, recreational or work activities because of substance use.

Risky use

- Recurrent use in physically unsafe situations.

- Continued use despite physical and psychological problems.

Physical dependence

- Developing tolerance—needing more of the substance to achieve its desired effect.

- Experiencing withdrawal symptoms after quitting or reducing use.

Note: Tolerance and withdrawal in the context of medical treatment — such as opioids prescribed to manage pain with cancer — would not be considered criteria for a substance use disorder.

Mild, moderate or severe SUD?

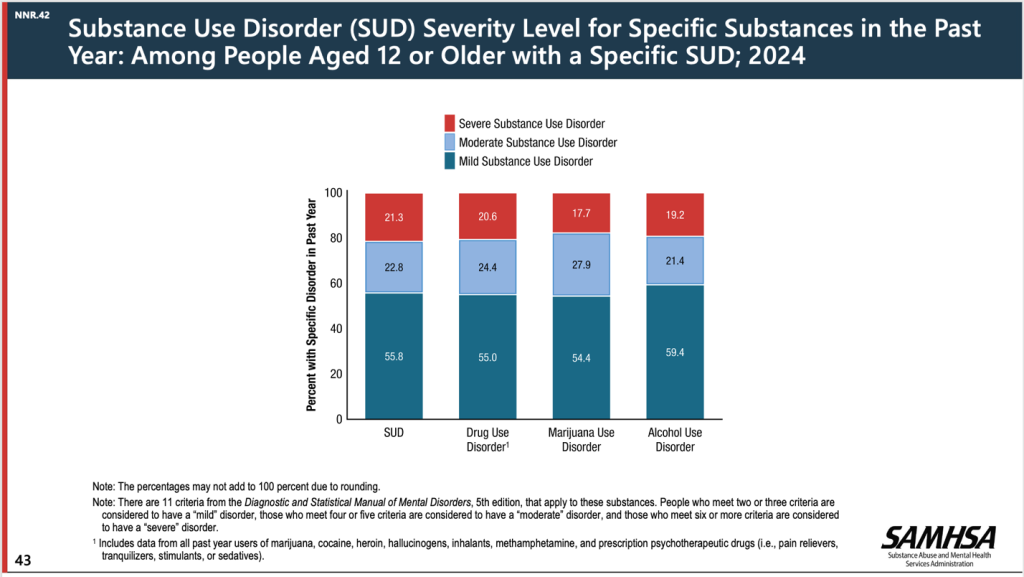

Substance use disorders are classified as mild if someone meets 2-3 criteria, moderate if they meet 4-5 criteria, or severe if they meet 6 or more.

So a severe substance use disorder is what most people understand as addiction — when loss of control over drug or alcohol use leads to risky use and dependence which disrupt someone’s ability to function.

How many people meet the criteria for a substance use disorder?

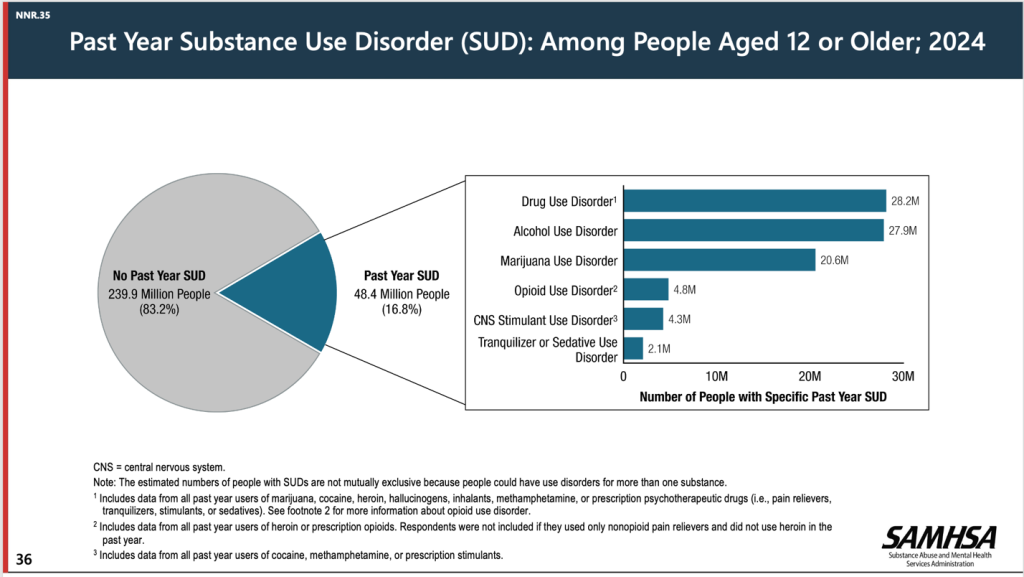

The answer to this question — 48.4 million people or nearly 17 percent of the U.S. population aged 12 or older — comes from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which is conducted annually, though staff who work on the survey have been impacted by government layoffs.

The survey doesn’t include some groups, such as people who are incarcerated or unhoused, and there’s a lag time between data collection and publication, but it’s generally considered representative based on statistical measures used to account for missed populations. Even so, some researchers have questioned whether NSDUH underestimates use of some substances, such as illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Most substance use disorders are mild

If you consider that one in six people 12 and older meet the minimum criteria for a substance use disorder, that may seem like a high percentage of the population, so it can be helpful to note that most SUDs (about 56 percent) are mild. That number is 55 percent when you look at the data for drug use disorders (not including alcohol). For alcohol use disorders, about 59 percent are mild.

Different patterns with different drugs

The pattern changes if you look at the data SAMHSA published for specific substances in 2023. (This graphic wasn’t included in the 2024 release). Although 55 percent of marijuana use disorders were mild, only 34 percent of cocaine use disorders were mild while 42 percent were severe.

For methamphetamine use disorders, just 28 percent were mild and 56 percent were severe.

Changes in diagnostic approach and increased population with substance use disorders

One reason the prevalence of substance use disorders is so high is due to a change in how drug and alcohol problems are diagnosed that occurred with the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) published in 2013.

With the fourth edition of the manual (DSM-4), a distinction was made between substance “abuse” and “dependence.” The former is similar to a mild substance use disorder and the latter to a severe substance use disorder, but they were considered different conditions — not just different degrees of the same illness.

The changes related to drug and alcohol diagnoses were hotly debated, within and outside research and treatment circles. Covering this controversy, a 2012 article in The New York Times warned, Addiction Diagnoses May Rise Under Guideline Changes, suggesting that the proposed DSM updates “could result in millions more people being diagnosed as addicts and pose huge consequences for health insurers and taxpayers.”

That is in fact what happened, though changes in the drug supply, the impact of COVID-19, and other factors may have also contributed to the sharp increase in people with SUDs.

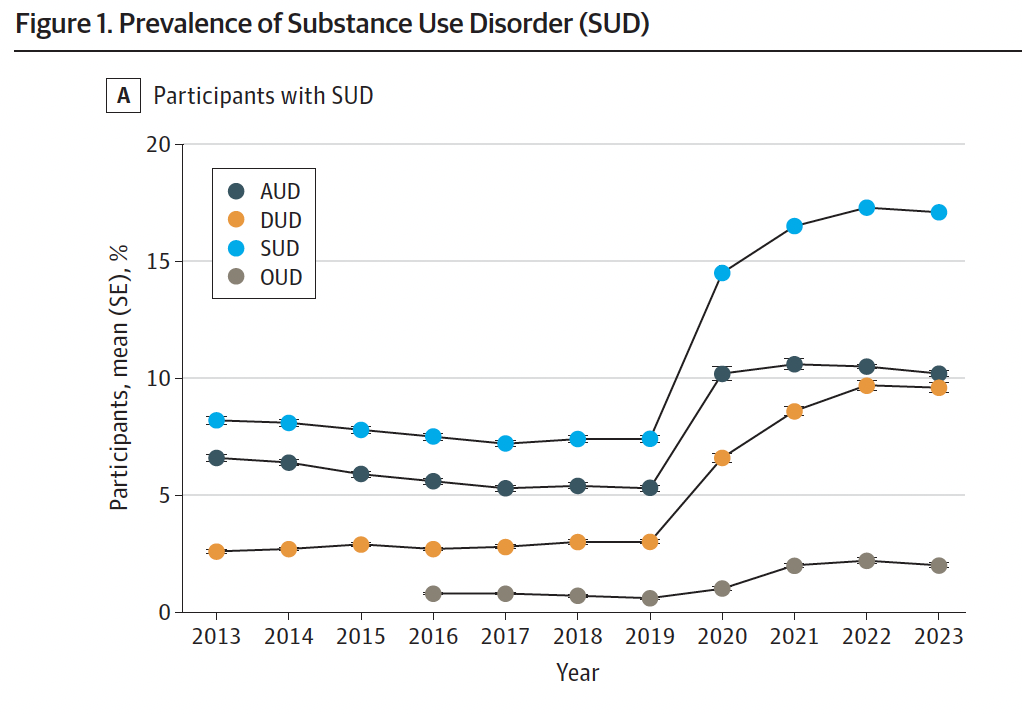

Using NSDUH data, researchers found that the prevalence of substance use disorders among people 12 and older more than doubled over a decade, increasing from 8.2% of the population in 2013 to 17.1% in 2023.

Figure 1, Prevalence of Substance Use Disorder (SUD), from Trends in Treatment Need and Receipt for Substance Use Disorders in the US, Liu et al., JAMA Network Open, 2025.

Why diagnosis criteria matter: Assessing treatment need and approach

In a journal article published in 2014, The Elimination of Abuse and Dependence in DSM-5 Substance Use Disorders: What Does This Mean for Treatment?, Albert M. Kopak and colleagues asked some key questions:

“First, does the severity index — defined as the total number of diagnostic criteria – truly represent variations of the same disorder? Or, are we dealing with distinct disorders that manifest common symptoms and behaviors along a defined continuum…?

Second, are there subsets of criteria which are more likely to represent certain severity levels? If so, how can these criteria best inform treatment programs to reduce relapse and achieve optimal outcomes?

Third, how should severity level inform the development of individualized treatment goals? Is total abstinence the best practice across the board or should other options be considered for less severe cases?”

This is a topic Jason Schwartz, an addiction professional and social worker, has been writing about since 2012 and revisited earlier this year: Substance use disorder sets off a cascade of category errors.

“As a category, SUD is about as helpful as pulmonary disease,” he writes. “It tells you something about the likely symptoms, but it could be acute, it could be chronic, it could be mild, it could be severe, it could be a minor inconvenience, or it could be disabling and something that shapes the person’s identity. It tells us nothing about the nature of the problem, the cause, the course, the severity, whether it requires treatment, the kind of treatment indicated, what problem resolution (recovery) looks like, or the implications for the patient, their loved ones, and the community.”

Takeaways for journalists

For journalists covering alcohol and drug problems, understanding the history and debate about substance use disorder criteria is important for educating people about SUDs and how they overlap (or don’t) with addiction. It’s also critical for interpreting data and tackling questions like who might be a candidate for treatment and what types of services may be helpful.

Researchers often talk about a “treatment gap,” but typically calculate the difference between who needed and received treatment using the NSDUH results for anyone who met at least two criteria for a substance use disorder: 48.4 million people. Yet these survey responses are not the same as a clinical diagnosis.

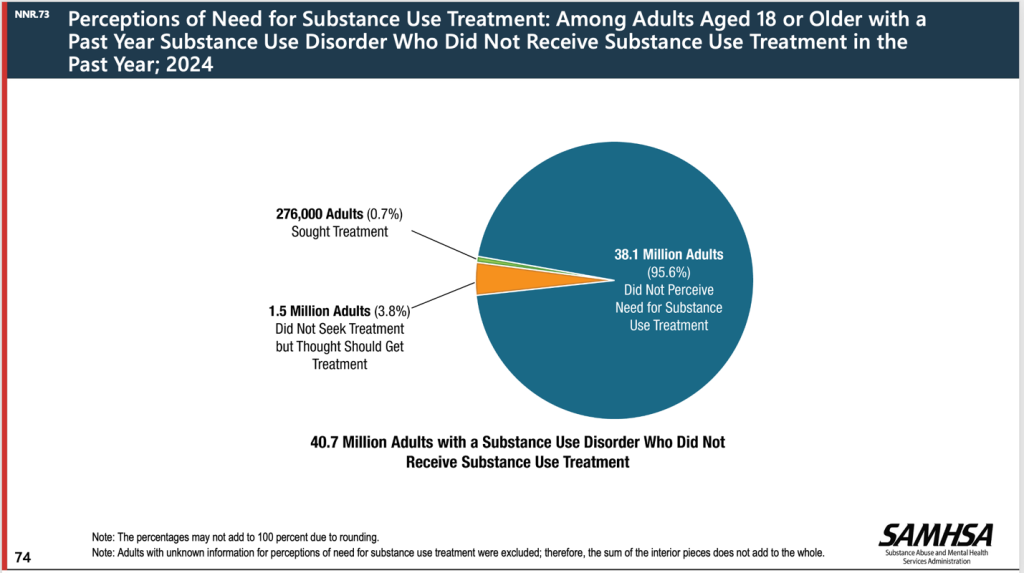

Data from that same survey show that nearly 96 percent of adults who had a substance use disorder in 2024 but didn’t receive treatment felt they didn’t need treatment. Maybe they pictured residential rehabilitation or an intensive outpatient program when they answered that question, but it’s possible some might have been more open to other services—like counseling or peer support to help reduce the harms caused by their substance use.

The 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 95.6 percent of adults who met at least two criteria for a substance use disorder did not perceive a need for treatment.

Regardless of whether “substance use disorder” is a less stigmatizing phrase, it captures a much larger population than people with addictions.

So for journalists covering alcohol and drugs, it’s important to be aware of the difference and ask questions about how these terms are used in interviews and research.

To sign up for email alerts when these monthly articles are published or to offer feedback about the guide as it takes shape, you can fill out this form or click the link below. I’m especially interested in finding out what questions or topics journalists would like to see included, including challenges reporters have encountered finding information or data. I’ll also be looking for suggestions from researchers, service providers, policymakers, advocates, and people personally impacted by substance use and addiction.

Cite this article

Stellin, Susan (2025, Sept. 3). Understanding the difference between substance use disorders and addiction. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/understanding-the-difference-between-substance-use-disorders-and-addiction/