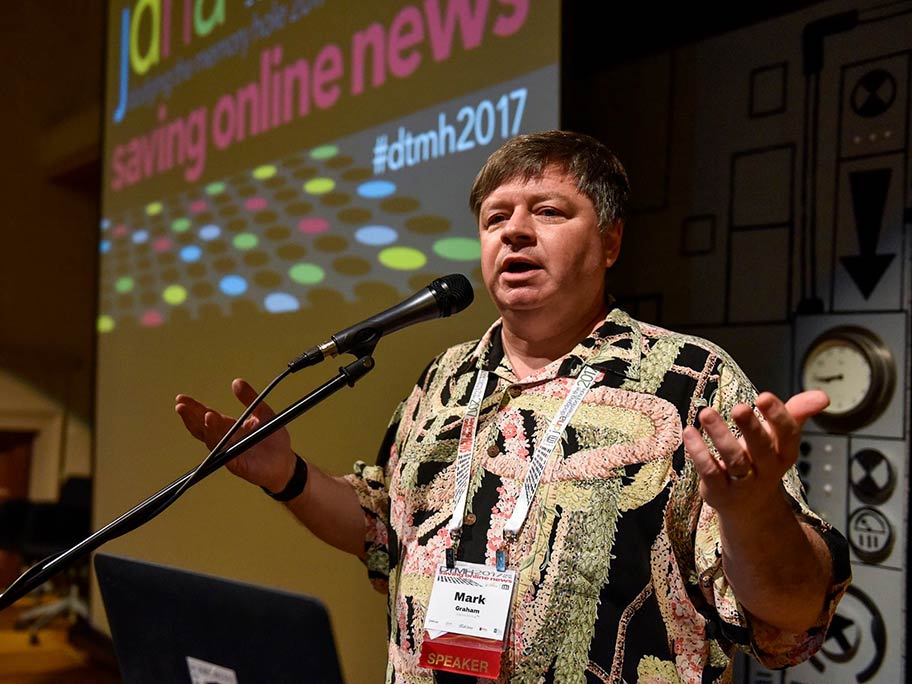

Mark Graham leads a discussion during the second day of Dodging the Memory Hole conference Thursday, Nov. 16, 2017, at the Internet Archive in San Francisco. Photo by Michael Cali.

Changing media landscape adds yet another challenge to archivists of born-digital news content

On Nov. 2, just shy of the yearlong anniversary of his presidential victory, President Donald Trump’s Twitter account seemingly dissolved into history. For a fascinating and exhilarating 11 minutes, murmurs and conspiracy theories swept the internet: Was it a technological glitch? Had President Trump deleted his own account? Or had Twitter interpreted Trump’s digital demands and digressions as a variation of hate speech, and so — in abiding by Twitter policy — shut down one of the most powerful voices in modern times?

It turned out a renegade contract employee, on his last day, decided to literally flip the switch on Trump’s presidential pulpit. The account was eventually restored, but not before the tech press doubled-down on Twitter for allowing such a misfire to happen. For technologists, internet archivists and historians, however, it was yet another reminder of a long-standing issue the cacophony of social media merely exacerbates: an urgency to preserve our digital history.

At Dodging the Memory Hole 2017, the fifth such forum sponsored by the Missouri School of Journalism’s Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the changing landscape of the news media — particularly in our current fraught political landscape — underpinned presentations by stakeholders and digital preservation practitioners who think about this issue on a daily basis.

Held this week at the Internet Archive in San Francisco, the conference’s name evokes the “memory hole” of George Orwell’s novel “1984,” in which photographs, documents — anything that conflicted with Big Brother’s dominant narrative — were tossed into a memory abyss and destroyed. Not only are technological systems and their financial resources currently insufficient for the amount of information we intend to store online, but the debate over who powers our news and the platforms that disseminate them — whether they’re journalists, politicians, trolls, citizens or technology companies — makes saving online news more important than ever.

Remarking on how newspapers and news websites are essential tools to educate and inform the public — and therefore contribute to the democratic process — Marc Weber, curatorial director at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, noted the extra weight fake news puts on the shoulders of digital historians and web archivists. “If you don’t have any archives, it’s all just equally debatable,” he said. “This makes it so much more urgent to preserve archives, to prove fake news against facts.”

At Dodging the Memory Hole 2017, the changing landscape of the news media — particularly in our current fraught political landscape — underpinned presentations by stakeholders and digital preservation practitioners who think about this issue on a daily basis.

How to effectively create digital repositories of data for researchers and journalists is a huge part of what Regina Lee Roberts investigates as a collection development librarian at Stanford University. Once a news story is published, preserving any public records or other evidence gathered for their stories is crucial — not just for debunking fake news, but for making this information accessible for others to build on. ProPublica, The New York Times and Politico are just a few news organizations that have started to invest heavily in retaining their data. “And then they’re kinda guarding it,” Roberts said with a rueful smile, adding that journalists also sometimes rush off to the next story before taking the time to load their data into any repository. Yet taking the information gathered for granted can sometimes have deleterious effects for journalists, she said: “They’ve seen their data disappear from stories they’ve written years ago.”

The elephant in the room at this year’s conference, Roberts observed, was the tension between making digital databases free and the sustainability model for news organizations. As the blinking blue lights of the Internet Archive’s servers hummed from the back wall of the conference’s main room, a few speakers emphasized how marginalized communities — who are already typically underwritten in history — often can’t access news about themselves if that information is behind a government or library paywall. Struggling news websites also create a journalist’s worst nightmare if they scrub their stories from the internet upon shutting down — as was the case recently with DNAInfo and the Gothamist, which abruptly shuttered the same day President Trump’s Twitter account mysteriously disappeared.

“Our screens can betray us,” said Brewster Kahle, the founder of the free Internet Archive, whose project the Wayback Machine proved a lifesaver for those journalists who were left scrambling to find their clips. A “taxonomy of problems” and questions exist when it comes to saving online news now, Kahle said. What is news? Who is a journalist in this era? How should we consider Donald Trump’s Twitter account? Not only that, but the rewriting of history among propagandists alongside the aggressive pace of news writing, headline-changing and tweet-deleting makes fighting these problems especially combative. The Internet Archive collects as much data every day as the text contained in the Library of Congress, Kahle said, but it can’t save a tweet seconds after it’s deleted. Certain countries — China being the biggest example — also block the Internet Archive.

Meanwhile, educating the public is absolutely crucial to making the work of web archivists worthwhile. “How do we instruct a generation that’s used to screens to go to a website? This is the reality that news is now,” he continued.

For Sharon Ringel, a research fellow at the Tow Center studying the archival practices of news organizations, the sense of community the conference fosters is the biggest impetus in helping to move forward toward these goals — because it’s only by collaborating with other institutions and individuals that saving all of this history will be possible.

“People hear the word ‘archive,’ and they think it’s not important enough because it’s the past and not ‘new,’ which is the essence of news,” she said. “But it is so important for future research and value.”

Comments