Preserving a visual record, Part 1

As a digital curator of journalism, I have a tendency to ask people — laypeople and journalists — what types of content they’d like to see or retrieve from news archives. Consistently, photography comes up as one of the top answers. Maybe it’s the immediacy of how images convey history and information: there’s less processing time and effort required than reading words. Or perhaps it’s because some photos have an emotional component that pulls you into and beyond the frame.

Even in the age of Photoshop and megapixels, photographic images convey a sense of authenticity that’s hard to beat. For all those reasons and more, it’s a good idea to keep those photos around for future generations.

One of the benefits of my office at the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute is its proximity to the Columbia Missourian, a daily newspaper produced by Missouri School of Journalism students and faculty. As a test laboratory for journalism, the Missourian offers a great opportunity to investigate the effects of the paradigm shift from analog to digital. For the past couple of years, I’ve been working with Missourian editors and staff to improve the usefulness of the paper’s published digital content.

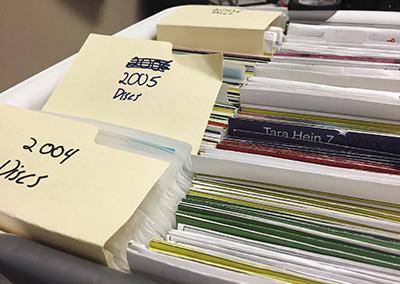

When I first asked Missourian photo editor Brian Kratzer about how the newspaper was preserving its digital photographs, he pointed to a nearby desk with a small stack of assorted hard drives of various vintages and to a filing cabinet stuffed with compact discs. This did not please me, but it did not surprise me, either. It’s a problem that is happening in newsrooms all over the world as journalists confront the consequences of producing news content in digital form.

In the days of photochemical photography, one could hang onto processed film rather easily: cut the film into strips, load them into paper or plastic holders, attach the date and some notes, stash them in a clean dry place and voilà, you had the beginnings of an archive. Today’s digital cameras produce binary “negatives” in the form of RAW files, often in proprietary formats. You can’t view these images without using a computer loaded with the proper software. After the RAW files are copied onto a hard drive, there’s no easy way to know exactly which pictures are contained within it.

For example, I could pull a negative or print from the 1880s, look at it by candlelight and immediately comprehend whether it’s a picture of a child, a bicycle or a house. Try that with an Amiga image file from the 1980s or a Kodak Photo CD disk from the 1990s. Both of those formats are obsolete and most people would need a digital forensics expert to retrieve them. Even with the most modern digital photography formats, you need electricity and a fairly powerful computer running the right software just to open and view them.

That’s a brief introduction to the differences between analog and digital archiving. In the arcane world of digital preservation, photos created using a digital imaging sensor (i.e., not scanned from photochemical prints or negatives) are called “born digital.” Distinct from traditional methods of archiving analog resources such as the printed page, preserving born-digital content requires a more active and ongoing set of activities designed to keep the content viable even as computer hardware, operating systems, applications, file formats and other aspects of the technology platform continuously evolve.

Next: It’s a RAID!

Comments