Journalists must play a vital role in fixing America’s false economic narrative

From the Federal Reserve to the U.S. Economic Development Administration to the American Planning Association, pressure is mounting in policy and planning circles to address the economic consequences of structural racism.

In an effort to reboot an economy still impacted by COVID-19, the inherited disparities of a pre-pandemic segregationist society have been laid bare across the spectrum of life in America — in education, housing, jobs, business, finance, healthcare, transportation, access to food and other vital resources. Leaders are learning they can ill-afford to maintain the pre-pandemic status quo of ignoring the most vulnerable populations while building a new inclusive economy in a post-pandemic society.

Corporations, too, are opening their eyes and wallets and pledging to confront discrimination and reverse chronic underinvestment in Black and Brown communities, many spurred to action by rallies for racial justice and an increasing body of research about the economic toll of White supremacy.

Consider: it will take 228 years for the average Black family to accrue the 2016 level of wealth of the average White family, according to Ever-Growing Gap, a report from the Institute for Policy Studies and the Corporation for Enterprise Development. For Latino families, it’s 84 years.

“By the time People of Color become the majority (in 2043), the racial wealth divide will not just be a racial and social justice issue impacting a particular group of people — it will be the single greatest economic issue facing our country,” conclude researchers Chuck Collins, Dedrick Asante-Muhammed, Josh Hoxie and Emanuel Nieves.

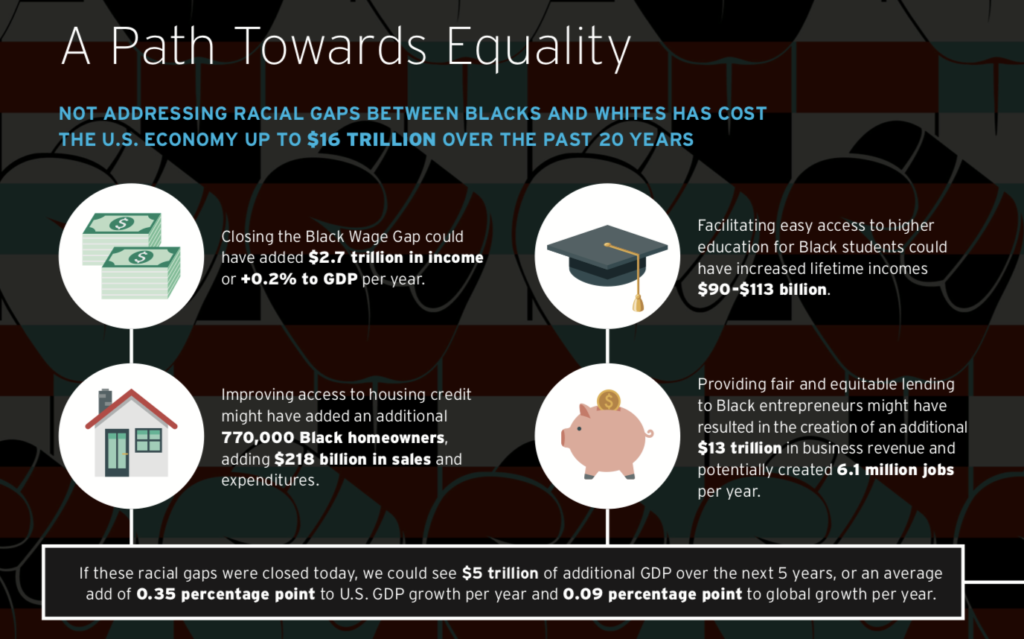

Already, racist policies and discriminatory practices against Black Americans have cost the country $16 trillion over the last 20 years, according to just released research by Citigroup economists Dana M. Peterson and Catherine L. Mann. Closing the Black wealth gap could add as much as $5 trillion to the economy over the next five years, they say.

“Racial inequality has always had an outsized cost, one that was thought to be paid only by underrepresented groups,” Citigroup Vice Chairman Raymond J. McGuire told Yahoo News. “What this report underscores is that this tariff is levied on us all, and particularly in the U.S., that cost has a real and tangible impact on our country’s economic output.

“Now, more than ever, we have a responsibility and an opportunity to confront this longstanding societal ill that has plagued Black and Brown people in this country for centuries, tally up the economic loss and as a society, commit to bring greater equity and prosperity to all.”

Bankers and economists aren’t the only ones in need of a course correction. For decades, journalists have largely reported on the U.S. economy as it tracks with the fortunes of the wealthy, with little sensitivity to income changes among the non-rich. As income inequality rises, news about the national economy tends to be more positive. As inequality decreases, economic news trends negative.

That’s what researchers Alan M. Jacobs, J. Scott Matthews, Timothy Hicks, and Eric Merkley discovered after analyzing news articles from 32 high-circulation U.S. newspapers over 30 years.

In their 2020 report, “Who’s News? Class-biased Economic Reporting in the United States,” the researchers blame the phenomenon on journalists’ tendency to cover the business cycle and to rely on big-picture indicators like gross domestic product, employment, and corporate performance when grading the economy, “paying little heed to the matter of who loses or gains as the economy expands and contracts.”

“To the extent that voters’ perceptions of the national economy are shaped by the media, the economy on which most voters have been voting has, in an important sense, not been theirs,” the report says.

There is another bias at play, one that results from a lack of diversity among the people who inform and produce news about the economy. When the default economic narrative is written by, for and about White people, it can’t help but contribute to public ignorance about the true extent of racial economic inequality. And that ignorance has important consequences for public policy, say Yale researchers Michael W. Kraus, Julian M. Rucker and Jennifer A. Richeson, who examined perceptions of Black — White differences in economic outcomes.

“Before citizens and policymakers can fully understand and appreciate the potential societal consequences of such a stark racial divide in economic outcomes, individuals must first be aware of its existence,” they write.

We’re encouraged by the increasing number of journalists and newsrooms taking a more inclusive and solutions-oriented approach to economic reporting:

Next City consistently illuminates ways that cities can be reimagined as equitable and inclusive, offering yearly Equitable Cities fellowships for journalists of color to uncover promising strategies for building economic mobility and investigate those that are contributing to inequality.

City Bureau, Outlier Media and Resolve Philly prioritize access and equity and focus on the information needs of communities systematically ignored by mainstream media.

The Solutions Journalism Network recently launched an economic mobility reporting initiative, led by Sarah Gustavus, to support nuanced coverage of what’s helping people achieve greater economic opportunity.

The Economic Hardship Reporting Project, sponsored by the Institute for Policy Studies, funds and co-publishes stories that humanize inequality.

The current class of Report for America Corps members includes dozens of journalists reporting on economic justice and related topics like equity in education, housing, health, criminal justice, immigration and the environment.

Mainstream media have their moments, too. The Atlantic keeps a sharp eye on the problem of racial inequities and how they manifest in economic and social disparities. Reveal’s year-long investigation uncovered generational systemic racist policies in banking and housing industries. Propublica’s report on how Black families are dispossessed of lands owned since the Reconstruction Era prompted congressional action. And the New York Times’ 1619 Project includes a powerful accounting of the brutality of American capitalism from slavery to present day.

But if the purpose of journalism is to help citizens make informed choices and hold government accountable, then the cumulative manner in which the media report on the economy constitutes a colossal failure. Until the shift in news coverage is commensurate with the depth, breadth and scope of the problem — and its solutions — the public will struggle to have the knowledge and tools to affect meaningful change in their communities.

So, how do we equip journalists to do better?

Creating an inclusive economy involves more than making existing policies and practices less racist and more equitable. It requires investments that increase productivity and prioritize wealth creation among the nation’s most vulnerable populations and establishing community conditions that are favorable for them to compete in an innovation economy. Only then can they own an equitable share of the American dream of prosperity and contribute to the overall economic competitiveness of the country.

Likewise, telling a more inclusive story of the economy requires more than pointing out racial disparities. Journalists need to interrogate the systemic segregationist policies and practices that create and sustain the conditions for those disparities to exist and persist, and also give more attention to what is working and why.

Here are 10 actions journalists can take to provide a more accurate and complete narrative of American prosperity:

- Educate yourself. Learn the history and continued effect of White supremacy on the U.S. economy and the well-being of all its citizens. Read the research. Stay current on local and national efforts, especially by Black, Indigenous and Communities of Color, to advance economic equity.

- Expand your field of view. Center the expertise of someone other than a White man. Tawanna Black, Jamie Bracey Green, Rebecca Adamson, Monica Garcia-Perez, Lisa D. Cook, Sandra Orozco-Aleman, Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman, Thea M. Lee, Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, Alessandra Fogli, Winona LaDuke, Nellie Liang, Jhacova Williams, Ebonya Washington, Wendy Edelberg, Gita Gopinath, Adela de la Torre, Tisha Lin Nakao Emerson, Dania Francis, Camille Busette, Johnathan Holified, Monique Woodard, Natalia Oberti Noguera and Carla Harris for starters.

- Shift your lens. Tell the story of the economy from the perspective of people and communities frequently marginalized by it. Better yet, hand over the mic and let people tell their own stories in their own words. Take care to portray people and places as valued assets and untapped opportunities in your region and not just as barriers to overcome. For inspiration on how to do strengths-based and solution-oriented reporting, check out the work of Oscar Perry Abello, senior economics correspondent for Next City.

- Show the upside. Educate the public on how Black, Latinx, Indigenous and other populations contribute to the economy and how much more competitive the U.S. would be if they could participate fully.

- Watch your words. Language about place matters because it can be used to justify actions taken toward people. Avoid using short-hand labels like “low-income,” “poor,” “high-poverty,” “struggling,” “blighted,” “disadvantaged,” “distressed,” “at-risk,” or other combinations of “deficit” plus “geography” to describe communities impacted by racism, disinvestment, physical destruction, and economic exclusion. From Jennifer S. Vey and Hannah Love of the Brookings Institution: “Just like the labels we attach to people, such language reduces these communities to only their challenges, while concealing the systemic forces inherent in segregationist policies and practices that caused those challenges and the systemic solutions needed to combat them.”

“To the extent that voters’ perceptions of the national economy are shaped by the media, the economy on which most voters have been voting has, in an important sense, not been theirs,” — from the report, “Who’s News? Class-biased Economic Reporting in the United States”

Such terms, they explain, paint an image of places beyond repair, where residents ought to move away from or that need to be ‘fixed’ by outsiders, disregarding a community’s strengths and assets as well as the dedicated community leaders that have long been leading strategies to improve neighborhood conditions. Learn more at the Brookings’ Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking.

- Boot the bootstrap. Rugged individualism — the myth that anyone in America can get ahead if they just work hard enough — is a common and harmful narrative many journalists use when reporting on Black, Indigenous and People of Color who overcome hardship on the road to success. “Pulled up by the bootstraps” stories shift the focus to individual actions and away from the systems that create inequity. If you’re going to report about someone thriving against the odds, make clear what those odds are and why they exist. A number of media have published insightful reports debunking the myth of meritocracy in America and in-depth analyses of the myth of economic mobility, such as this one by Evan Horowitz published by NBC News, Yet the myth itself remains the prevailing narrative. This is a clear indicator of the failure of media to correct a harmful narrative that props up the false ideology inherited from a 20th century society steeped in White supremacy.

- Get a new yardstick. When assessing the state of the economy, look beyond the business cycle and indicators like GDP, the stock market, and consumer confidence and determine who is benefitting and who is not. Pay attention to wages, income distribution, household wealth, homeownership, educational attainment, and employer-based firms — and always disaggregate the data by race and place.

- Pay particular attention to ownership. Prosperity is about getting to a place of ownership — of homes, of lands, of businesses that are growing and becoming employer businesses, and of investments that provide positive returns. Without ownership, there is no opportunity for Black and Brown populations to pass down any transferrable wealth.

- Read your CEDS. The country is divided into Economic Development Districts and every district must have Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) — a five-year locally-based plan for maximizing a region’s economic potential. How, if at all, does the plan improve the conditions and outcomes for the region’s most vulnerable populations? What are the outcomes, how are they being measured, and what investments are being made to achieve them?

- Be accountable. Ask yourself, who is benefitting from your journalism and at whose expense? As this ground-breaking article by Harry Backlund of City Bureau notes, the preponderance of journalistic resources go into serving the abstract needs of the comfortable few, ignoring the basic information needs of a great many.

“Journalists routinely cover inequity as an abstract phenomenon that can be observed and remarked upon from afar, but it’s a rare media organization that would produce a guide for navigating rural poverty, or managing an opioid addiction, or handling your lease when you’re getting gentrified out of your neighborhood,” Backlund wrote.

“Journalists have a huge amount of power to control the flow of information and shape public narratives, yet we have no structure with which to make sense of that power or let others hold us accountable. And we can’t claim to address the civic needs of a democracy if we have no strategy for meeting the basic information needs of those who live in it.”

Mike Green is chief strategist for the National Institute for Inclusive Competitiveness, a national nonprofit focused on developing economic strategies to improve the competitive performance of underrepresented populations and build inclusive sustainable regional economies. Mike is a cultural economist, consultant, speaker and former journalist.

Linda Miller is an experienced journalist, media innovator, and consultant to The Diversity Institute. She led the Public Insight Network and co-launched an initiative focused on changing racial narratives in Minnesota media. She’s working with RJI to develop inclusive economic and engagement strategies for journalism.

Coming soon: RJI talks with Oscar Perry Abello, senior economics correspondent for Next City.