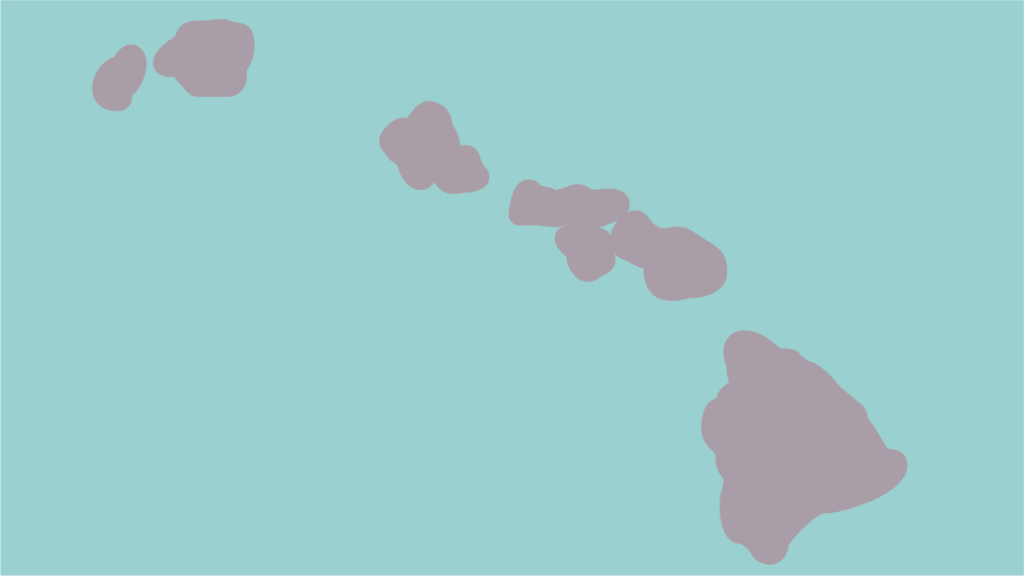

Hawaii

Anti-SLAPP protection

The “Hawaii Public Expression Protections Act” (2022 Hi. §34 CH. 634F) was passed in 2022. The act replacedthe state’s first anti-SLAPP legislation, enacted in 2002, which faced criticism for its limited scope and insufficient free speech protections, earning mediocre ratings from advocacy organizations.

Law summary

Hawaii’s anti-SLAPP law applies broadly to cases based on a person’s “exercise of the right of freedom of speech or of the press, the right to assemble or petition, or the right of association, guaranteed by the United States Constitution or the Hawaii State Constitution, on a matter of public concern” (HRS § 634G-2(a)(3). It also applies to lawsuits based on a person’s communications in legislative, executive, judicial, administrative, or other government proceedings and to communication on issues under consideration by any of those bodies (HRS § 634G-2(a)(1)–(2)).

Legal actions

Hawaii’s anti-SLAPP law includes four key features to protect publishers:

- Motion hearing timeline: A special motion to dismiss must be filed within 60 days of receiving the complaint, and the court must hear it within 60 days of filing, extendable for good cause or limited discovery (HRS §§ 634G-3(a), 634G-4).

- Two-step analysis: The court first determines if the anti-SLAPP statute applies. If it does, the court checks if the responding party has a prima facie case or if the moving party shows the claim fails legally or factually (HRS § 634G-6).

- Attorney fees: The winning party on a special motion to dismiss recovers costs and fees. If the motion is frivolous or intended to delay, the responding party recovers fees (HRS § 634G-9).

Helpful cases

The “Hawaii Public Expression Protections Act” is relatively new. The first case below showcases the judicial interpretation of SLAPP in the non-media context, while the rest illustrate how the courts navigated the balance between protecting free speech and addressing defamation claims.

Domingo v. Nutter & Company (2023)

Faustino Dasalla Domingo and Elton Lane Namahoe, Sr., filed wrongful foreclosure and related claims against James B. Nutter & Company and its attorneys, alleging misconduct, including fraud. This case involved complex issues of legal malpractice, wrongful foreclosure, intentional infliction of emotional distress, unfair trade practices, and elder abuse. However, in this analysis, we focus on the fact that the attorney defendants argued that the plaintiffs’ fraud on the court claim should be dismissed as a SLAPP under Hawaii Revised Statutes Chapter 634F. The attorney defendants stated the fraud on the court claim lacked substantial justification and was solely based on their participation in the foreclosure process, which should be protected under anti-SLAPP laws. However, the court found that the plaintiffs, Namahoe and Domingo, elderly individuals allegedly harmed by wrongful foreclosures on their reverse mortgages, presented a case that did not violate the anti-SLAPP statute. The court found that the attorney defendants had fraudulently affirmed the adequacy of the foreclosure basis, which significantly contributed to an unwarranted foreclosure action against the plaintiffs. The plaintiffs’ complaint was deemed to have substantial justification and was not based solely on the attorney defendants’ participation in governmental proceedings. The court concluded that the plaintiffs’ action to seek redress was justified and not intended to silence the defendants’ involvement in governmental activities.

Perry v. Perez-Wendt (2013)

The Hawaii Intermediate Court of Appeals ruled on the applicability of the state’s anti-SLAPP statute that was in effect until June 2022. In this case, a prospective county attorney filed a lawsuit against several individuals, alleging they influenced the mayor to withdraw his job offer. The claims included interference, defamation, and other related torts. The defendants sought to dismiss the case under the anti-SLAPP statute, arguing that their communication with the mayor and the filing of a complaint with the Office of Disciplinary Counsel constituted protected public participation. The court held that unsolicited, informal communication with government officials did not qualify as “testimony” under the anti-SLAPP statute and affirmed the lower court’s denial of the motion to dismiss, concluding that the defendants’ actions did not meet the statutory definition of public participation.

Wilson v. Freitas (2009)

Waldorf Roy Wilson II, a convicted sex offender, sued a few individuals, including the authors and publishers of the articles in the Honolulu Magazine and The Garden Island newspaper, alleging that they had defamed him by labeling him as a murderer in connection with an investigation into two murders and an attempted murder in 2000. The Hawaii Intermediate Court of Appeals affirmed the dismissal of Wilson’s complaint, finding that the media defendants were not liable for defamation. The court concluded that the media’s coverage and statements about Wilson were protected under the First Amendment, as they were related to matters of public concern and did not meet the legal standards for defamation.

Gold v. Harrison (1998)

Steven Philip Gold and Scott Howard Whitney filed a defamation lawsuit against George Harrison, The Honolulu Advertiser, and reporter Edwin Tanji. The plaintiffs alleged that Harrison made defamatory statements about them, which were published in an article written by Tanji for The Honolulu Advertiser. However, the Supreme Court of Hawaii upheld the circuit court’s decision to grant summary judgment in favor of Harrison and the co-defendants, determining that Harrison’s statements were constitutionally protected as rhetorical hyperbole.

Legislative activity

No current legal activities.

Of note

In 2022, Hawaii became the third state to adopt the Uniform Law Commission’s model for anti-SLAPP laws, the Uniform Public Expression Protection Act (UPEPA), following Kentucky and Washington.