Ilia Blinderman is The Pudding’s Senior Journalist-Engineer and one of the journalists behind 30 Years of American Anxieties.

Honoring the vulnerability of people’s stories when designing projects

A conversation with Ilia Blinderman, Senior Journalist-Engineer at The Pudding

We, myself and fellow Innovation in Focus Student Staffer, Beatričė Bankauskaitė, partnered with the Prison Journalism Project (PJP) to display their “What’s it like to be you?” project. With over 50 submissions from incarcerated writers, we tested different ways of presenting write-in submissions within the restrictions of Newspack. The process was driven by trial and error with one main goal: allowing visitors to not only read the submissions but feel them as well.

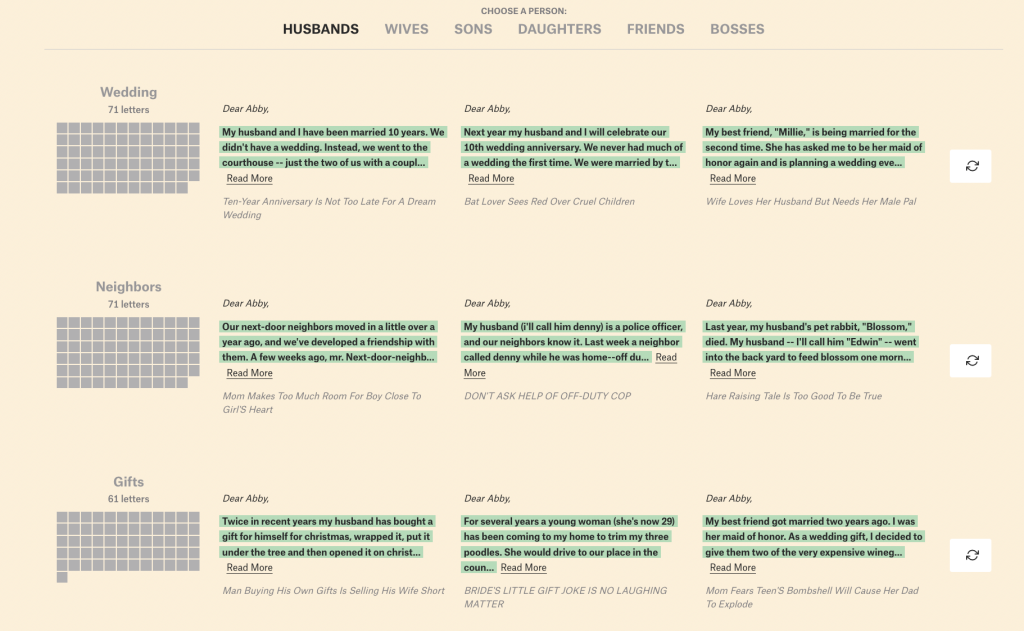

When researching other submission-based projects, we were inspired by The Pudding’s 30 Years of American Anxieties. In this project, Ilia Blinderman, Caitlyn Ralph, Russell Goldernberg and Thoka Maer took submissions from Dear Abby, America’s longest running advice column, and found visually interesting ways to display reader’s recurring concerns. Through animated graphics and interactive data visualizations, 30 Years of American Anxieties presented itself as the exemplar for our efforts.

For this Q&A, we spoke to Ilia Blinderman about data-driven storytelling and journalistic responsibility when handling vulnerable contributed content.

Oliphant: What’s your background in digital storytelling?

Blinderman: Like many folks that are in data, I don’t have a cookie cutter background. I spent a little bit of time freelancing as a writer, and then got a little bit tired of the fact that I didn’t feel like there was a lot of rigor to a lot of journalism. It was the very early stages of the period when click-baiting, high tech journalism became popular. So I was getting really frustrated with that.I thought, “Well, if I’m not in academia, and I don’t like a lot of mainstream journalism, what would I be excited about?”

Then I heard about data journalism; which would allow me to combine these two interests. In New York, I tried out this program at Columbia called The Lede. I finished that in 2014. Ever since then, I’ve freelanced and worked on some personal projects, but 2016 onwards I’ve been with Polygraph.

It’s really just a matter of asking, “What can we do to help people understand the experiences of others?”

Oliphant: Did misinformation and reader feedback have an influence over your career path?

Blinderman: I think what I really wanted was a greater appreciation for method. As a journalist, you especially need to be critical, because when you’re reporting, your work is going to influence others, the whole point is to take something that you found and then disseminate it. So you have this additional responsibility to get things right. I’m always struggling with that.

I think that data journalism doesn’t always get everything right. But at least there’s a greater appreciation of that moment of skepticism and doubt. It’s an appreciation for the critical thinking that needs to permeate everything you do.

Oliphant: How was the 30 years of American Anxieties project different from your other work in terms of how you displayed write-in submissions from Dear Abby letters?

Blinderman: With write-ins, it’s not someone in their network seeing the writing. There’s a vulnerability there; there’s a concentration of humans struggling. I think that if you’re a compassionate person, you’re drawn to doing your best to highlight these things as respectfully as you can and to just appreciate the human quality of it all.

It’s not like stories about what kind of music is popular with Millennials versus with Gen Z. I’ve done those stories, but I don’t necessarily have that immediate personal connection. I’m interested to see what people listen to, but I don’t think it affects me as a human being in the same way as reading about someone having a really difficult time. Personally, with these letters, you get the sense that the writers have no one to ask for advice. I think that’s really effective.

That’s probably the biggest hesitation we had with this piece. The challenge was not really from a visual standpoint. But as a baseline, we focused on making these letters as straightforward to read as possible, because we really wanted to highlight people’s experiences here.

It’s not about a pretty visualization that I can make. It’s about trying to impart that same impression onto our readers that I got when I started looking at the letters. The only way that I could do that is to just be a conduit to the letters.

Oliphant: In making this piece for The Pudding, what worked and what didn’t, when you were trying to put all these submissions together in an innovative way?

Blinderman: We went through a few design sprints. In total, maybe three or four iterations of this project existed at one point. The guiding philosophy and litmus test for each of the charts was whether or not the focus is on the abstract chart, or on the individual letters. And anytime we started to stray from highlighting the letters, we realized that we were not heading in the right direction.

There’s actually a GIF towards the bottom of the page, where we clustered some of the concerns from the letters, and it fades from just a whole bunch of dots, to a scatterplot, to dots with a bunch with text annotations on top.

We were considering that as a chart for a while until we realized like, look, we’re forcing the user to hover over certain areas, and we’re not pulling any of these letters out for them.

Whatever we could do to minimize the friction between the user and reading the letters we did. It’s a small interaction that we could erase to make that process easier. It’s really just a matter of asking, “What can we do to help people understand the experiences of others?”

Oliphant: Do you have any additional wisdom that you wanted to share for anyone who is looking to take on a project presenting contributed content?

Blinderman: I think that goodwill and compassion go a long way towards shaping a story in a respectful and caring manner. Approach all the submissions, and all the writers as people who have struggled and are struggling and are doing their best to put something out into the world that’s meaningful.

And knowing that you’re an essential part of that and remembering that you’re, in some small way, honoring them by helping bring their stories forward is probably the biggest consideration. The key thing to remember is that everyone’s doing their best and it’s not the same as a fluff story. As long as you approach it in that way, and as long as you’re being compassionate and caring about the people you’re dealing with you’ll probably end up in the right place.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity by Mikaela Rodenbaugh and Kat Duncan.