Making pictures in an upturned world

An analysis of photojournalists’ motivations for covering COVID-19

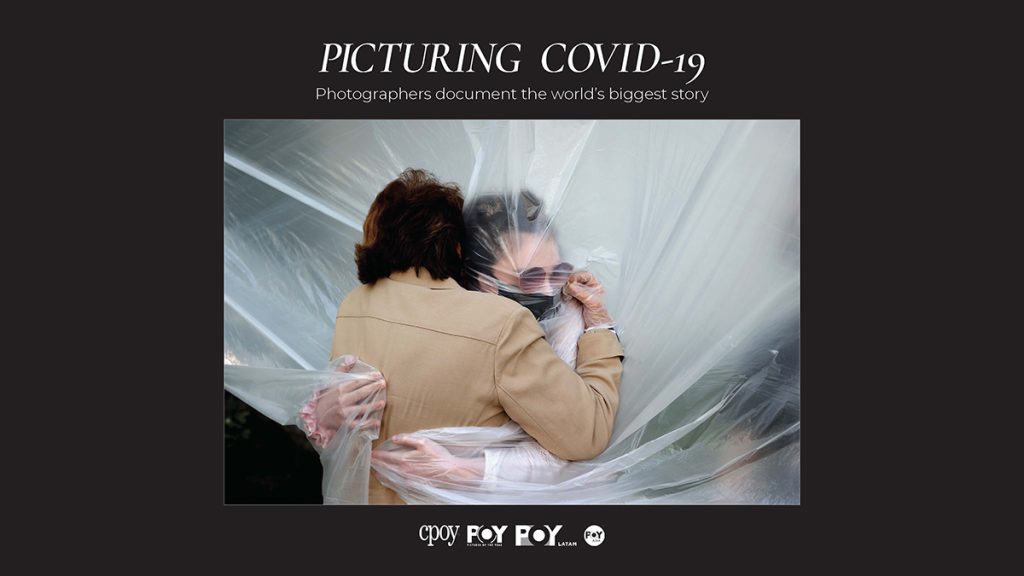

As part of her master’s project, Emmalee Reed (MA ’22 in Visual Editing and Management, BJ ’20 in Photojournalism) designed and edited a book of more than 200 photographs related to COVID-19 from the 2020 winners in POYi, CPOY, POY Asia and POY Latam. The article includes example pages from the book.

She will also present her research at the Visual Communication Conference (VisCom 36) at Cannon Beach, Oregon, on June 18, 2022.

Rarely does a story break that encompasses the whole world, but the COVID-19 pandemic did just that when it began in 2020. Months of lockdowns, isolation and sickness ensued in the pandemic that would touch every corner of the planet. At least 3.3 million people died COVID-related deaths in 2020, according to the World Health Organization.

Photographers around the world documented the pandemic, pushed by one reason or another to take photographs of their experience, their community or a different facet of life affected by COVID-19. Some went out into the world to photograph while others turned their lenses on themselves in lockdown. The pandemic story, which affected so many, provides an opportunity to investigate what draws photographers to take pictures.

To explore the influences that pushed photographers to document the pandemic and how those influences impacted their work, I sought out seven photographers whose work was awarded in the COVID categories of the POY-family photojournalism competitions, including Pictures of the Year, College Photographer of the Year, Pictures of the Year Asia and Pictures of the Year Latam: Eitan Abramovich, Shafkat Anowar, Amit Chakravarty, Lauren DeCicca, Rosem Morton, Colton Rothwell and Elisabetta Zavoli. Through semi-structured phone interviews, this article shows some ways photographers adapted to the pandemic and why they kept working during this difficult time.

Documenting the pandemic

Some photographers interviewed said that they photographed the pandemic because it was a big story and a historical moment that needed to be documented. Both photographers that did news and personal work expressed a drive to photograph the pandemic because it felt important.

“This huge story came, and I was thinking to myself, ‘What the f*** am I doing sitting in the desk?’” Eitan Abramovich said. “I need to go out and take pictures. The office closed, we all started to work virtually, and I started thinking ‘I need to do something. I need to document this story that is going on.’”

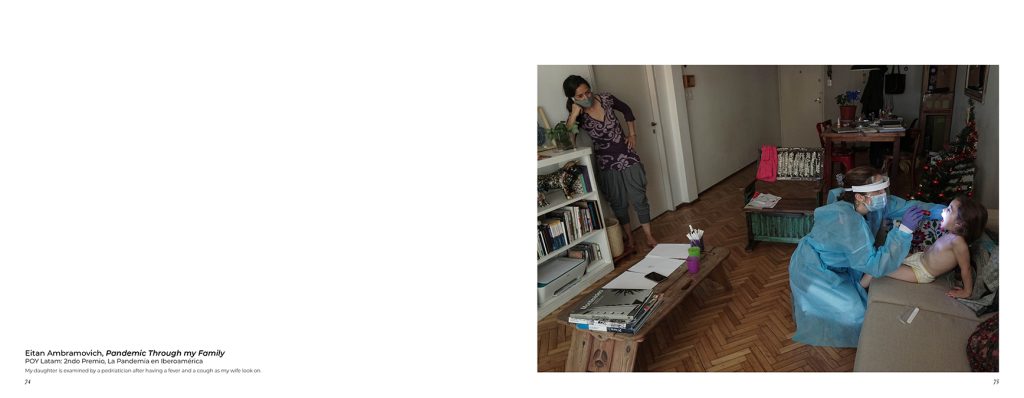

Abramovich, a photo editor for Agence France-Presse, turned his lens on his family and documented their experience during the lockdown in Uruguay. His project, “Pandemic Through my Family,” placed second in POY Latam’s La Pandemia en Iberoamérica category.

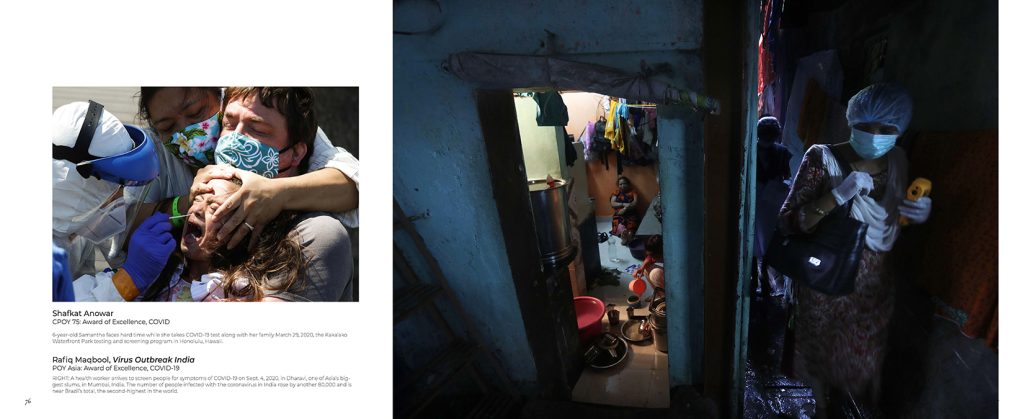

An impulse to document also affected Shafkat Anowar, who was a student at the University of Hawaii at Manoa at the start of the pandemic. He said he and other student photographers wanted to go out and photograph their community but were advised by professionals to not take the risk and to stay home. After months of not taking any photos, Anowar went to photograph a COVID testing site.

One of his photos taken at the testing site earned an Award of Excellence in CPOY’s COVID category. After his initial pandemic shoot, Anowar began documenting his community and how it dealt with the pandemic. When other photographers traveled to cover Black Lives Matter protests, Anowar stayed in Hawaii and kept doing his community-based photography.

“I’m like ‘I’m not going because that is not my story to tell,’” he said. “Instead, I will just stay here, back in my house, and try to find something here,’ because I needed to show what underprivileged societies and communities looked like.”

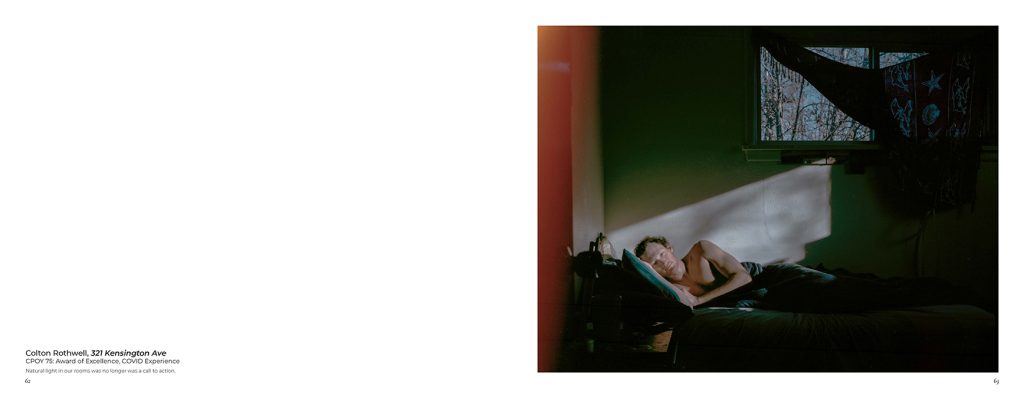

Colton Rothwell, a student at the University of Montana, felt a similar need to document when working his project about isolation, “321 Kensington Ave,” which earned an Award of Excellence in CPOY’s COVID Experience category.

“From a historical standpoint, I feel like my work is important,” Rothwell said. “It’s not breaking news. It definitely has more of an aesthetic sensibility. But I’m imagining looking back on this work in 30 years, it’ll be really intriguing.”

The pandemic quickly became the story of the year. Photographers expressed how quickly everything became a story. The pandemic touched everything.

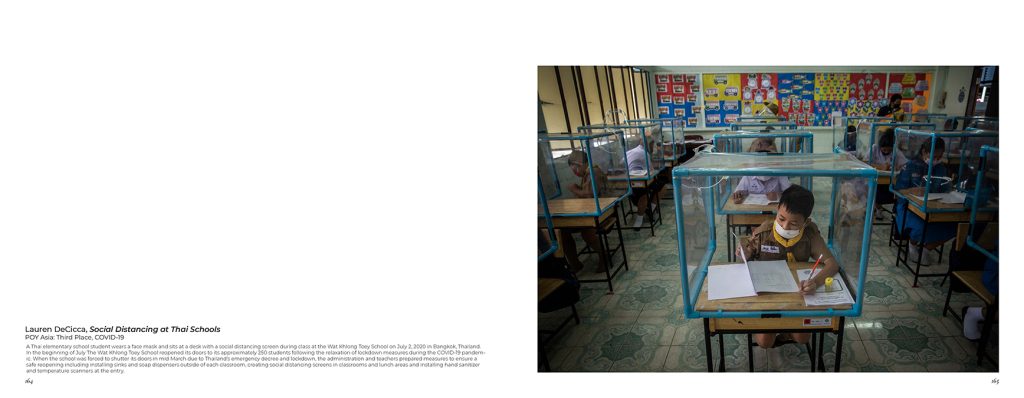

“Social distancing on the train was suddenly a story, or the park closing was suddenly a story, people wearing masks was a story,” Lauren DeCicca, a freelance photographer based in Thailand, said. “So it was like, every little thing. Like a grocery store, the toilet paper aisle was a story. And it just became so weird. I was so busy shooting my daily life.”

DeCicca’s photo of a Thai elementary school student sitting at a desk with a social distancing screen placed third in POY Asia’s COVID-19 category.

“Sometimes it was depressive, scary,” Abramovich said. “But for a photographer, it was like a mine of gold, you know, everything was part of the story.”

Photography as therapy

While most participants covered the pandemic because it was a big story, an equal number said they made photos during the pandemic as a coping mechanism. Photographers making expressive work as well as those that did more traditional photojournalism described photography as therapeutic.

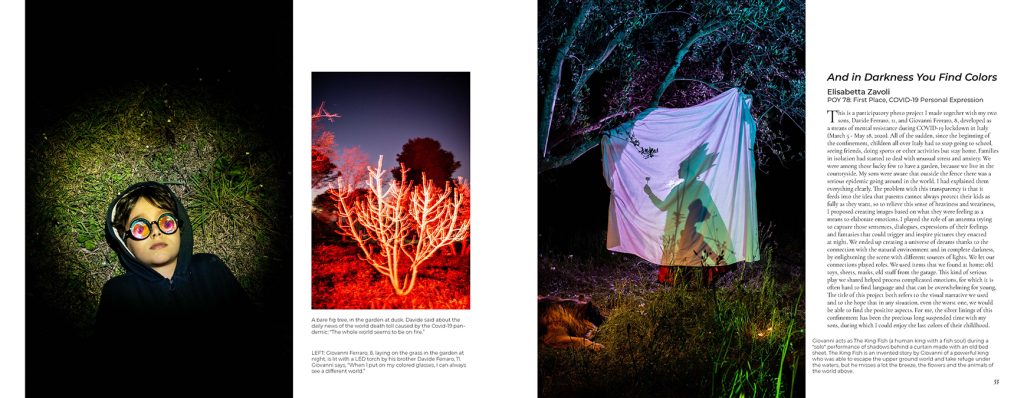

This was the primary motivation behind freelance photographer Elisabetta Zavoli’s project, “And in Darkness You Find Colors,” which won first place in POY’s COVID-19 Personal Expression category. Zavoli collaborated with her two young sons to design intricate sets, light them with colored lights and photograph them at night. The scene construction and picture making, Zavoli said, helped them cope during two and a half months of strict lockdown in Italy. Zavoli’s main purpose in taking photos was to help her children process their emotions about the pandemic.

“At the beginning, it was more like a way to play and to distract my sons from being too much overwhelmed or too much afraid of the situation,” she said.

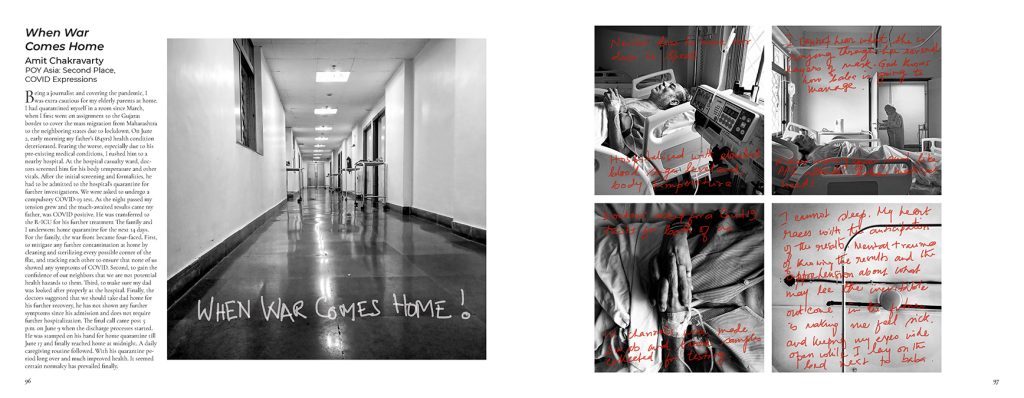

Only later did Zavoli compile the photos into a photo essay. Photographing without an end-goal was common among the photographers interviewed. Amit Chakravarty, a staff photographer for the Indian Express in Mumbai, photographed his father while he was in the hospital being treated for COVID-19 as a way to process his fear.

“Photographing is very instinctive, you know, and that also triggered me to be like, ‘Maybe this is it, so why not do something?’” Chakravarty said. “Maybe something in terms of my fear. I don’t know what happened at that point of time. I started shooting. Random. I didn’t have anything on my mind.”

Chakravarty later scrolled through the photos on his phone and realized he might have a project. Chakravarty’s “When War Comes Home” placed second in POY Asia’s Covid Expressions category.

Some photographers viewed their photo projects as distractions from the pandemic, even while their work was closely tied to their pandemic experience.

Rosem Morton, a documentary photographer and nurse in Baltimore, said that even though she was feeling the effects of working a lot during the pandemic, the time she spent photographing was valuable. Her project, “Donning and Doffing,” was a finalist in POY’s COVID-19 Personal Expression category.

“It’s like a perfect distraction for this time to continue to contribute what you can,” Morton said.

Abramovich said photographing his family was therapeutic, though his life felt “24 hours a day COVID.”

“In a way, taking pictures of my family, seeing my children — they didn’t really care what was going on, for them it was kind of a party — it cheered me up,” Abramovich said.

For other photographers, just the process of making something during the pandemic was beneficial to their mental health. While jobs were canceled and lockdowns set in, photography was a way to keep going.

Rothwell said he made pictures of himself and his friends during lockdown to “make sense of what was going on,” to “pass the time” and “keep sane.”

Anowar remained isolated at home for much of the beginning of the pandemic after losing his job as an event manager.

“Starting up the pandemic, I did not photograph anything,” Anowar said, “and when you are not creating anything as an artist, you are questioning yourself. A lot of depression and anxiety comes in. And then at one point I became a little bit frustrated, because I feel like it was more than six months that I did not create any work. I needed to create something.”

Anowar’s passion is political photography, but he shifted into a more documentary focus to start his freelance career in Hawaii. He said the compromise was worth it to keep working and described being happy to photograph a woman wearing a mask and praying on the beach.

“Those were some of the very small moments, intangible moments, that really kept me going,” Anowar said. “And I needed those.”

Community photography and public understanding

Many photographers said that showing how their family or community was affected by the pandemic was important. They also expressed the value of shared stories and creating work that other people could relate to.

Morton said that her primary purpose in photography is to connect with people and share stories so people can find similarities. Her nine and a half years as a nurse provided experience that she felt vital to her photographic work.

Her project documents her experience as a frontline health care worker. Morton’s partner also works as a nurse and was featured in the project.

“I feel like both of us going through this experience offers a unique point of view, to really offer public understanding on what it’s like during the early days of the pandemic when there were so many unknowns,” she said.

Abramovich and Rothwell were both bolstered by the desire to share work that is relatable to others. Abramovich said he wasn’t sure about sharing his project about his family because of the intimacy of the photos. When he posted some on Instagram, however, he received support from people who were impressed and encouraged him to continue.

“I said to myself, ‘Well, you have a different point of view of the pandemic,’” Abramovich said. “I thought millions of parents or families are passing through the same, so that’s a good story to tell.”

Similarly, Rothwell felt his isolation project was important because it was a story that other people could relate to.

“The majority of that body of work is about relationships,” he said. “I think that’s something a lot of people experienced during the pandemic. Changing relationships, tension on relationships, maybe relationships getting stronger. That fluidity, I think, is really important that people can see in my work and relate to and feel comfort in.”

Job impacts

Employment and organizational influences were often an important factor in photographers’ pandemic experience. Some began photographing the pandemic as a normal news story because it was their job. Staff photographer Chakravarty said his first COVID-19 photos were of people wearing masks on the train. One day, there were more people wearing masks than previous days.

“I just shot a few pictures and went to the office, and they printed it for the next day,” he said.

DeCicca said her COVID experience happened “really quick.” Her first pandemic assignment was photographing her arrival on the first temperature-scanned flight to Thailand. The same flight contained the first case of COVID-19 from abroad found in Thailand. She said the pandemic was weird to cover because everything became important to the story.

When the main story in Thailand shifted from lockdown to the economic effects of border closures, DeCicca shifted her focus, following the important news. DeCicca was busier than ever during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, she was the main stringer for Getty in Thailand and freelanced for other publications on stories around Southeast Asia. When the pandemic hit, she said the market was saturated with many photographers stuck in Thailand, so everyone had one main client. During the pandemic, she worked almost exclusively for Getty.

While DeCicca and Chakravarty secured assignments or remained employed, others were pushed to change courses and work on projects they normally wouldn’t.

Zavoli, who lives in rural Italy, didn’t have any freelance assignments during the pandemic because of work restrictions. She said a work permit was needed to leave lockdown and most assignments were going to photographers already living in big cities to avoid excess travel.

In lockdown, Zavoli felt free of editorial pressure and was able to work on a project just for herself and her sons. “It was a surprise because I was really enjoying photography,” she said. “It was many years that I couldn’t do something just for touching my soul like in this project.”

Abramovich recently switched from being a photographer to a photo editor. His new role prevented him from photographing COVID-19 as a news photojournalist would, so he focused instead on his family.

“Suddenly I realized that the story was inside my house, my family, and I started to just document it for myself,” he said.

Pandemic effects on photography

Many, including Morton, Abramovich and Zavoli, shifted their lens from a news focus to themselves and their personal experience. Anowar also shifted his focus from hard news photojournalism to documentary, community-based photography when he decided to stay at home and document his community. This was his first experience with documentary photography, a “drastic change,” he said.

DeCicca noted her photography grew stronger when her focus shifted from a more regional outlook to one that was Thailand-specific. When she couldn’t travel outside of Thailand, she focused on the stories in her area.

“I don’t think I realized how scattered I was beforehand, you know, trying to jump from story to story, from country to country and not really diving deep and finding out what’s happening,” DeCicca said. “I think my photography has benefitted from staying in one place.”

Other photographers saw stark visual changes in the style of their photography. Most of these changes were due to the impulsive, instinctive and expressive nature of the projects. When the impulse to document struck while accompanying his father in the hospital, Chakravarty took photos on his cell phone. He didn’t have his usual camera with him. Later, when looking through the photos, Chakravarty realized that he wanted to talk about certain things that happened or his father felt during that time that were unable to be shown visually. He “started scribbling” in a notebook and superimposed those thoughts onto the images.

The pandemic forced Rothwell to reinvent himself and use the equipment and subjects he had on hand to document his experience. He said his project, “321 Kensington Ave,” was unlike any of the work he made previously. Rothwell, who was used to using natural light and working with medium format film, had several strobes with him when lockdown began.

“I think [lockdown] just made me really think about my process about spaces differently,” he said. “Like being able to open a whole world of possibilities because I didn’t have to wait for natural light. I was able to just explore my process in a new way that was really neat.”

Harder, better

The influences that drove photographers to cover the pandemic had tangible impacts on both the photographers and the work they made. Despite the difficulties, many of the photographers described success and growth. Anowar’s freelance career flourished after his shift to documentary photography. Morton said the pandemic “solidified the kind of work” she was creating. Zavoli made a project with her sons that she said expanded her soul. DeCicca said the pandemic made the photography community closer.

“It’s of course made things harder, but I think, hopefully, it’s made us all a little bit better as well,” DeCicca said.

Comments