Three disability questions every editor should ask

Accessible editing practices elevate disabled voices, eliminates ableism and makes journalism more accurate

Newsrooms are slowly seeing the need to make accessibility more than an afterthought. Our industry is beyond late to the realization and is due for a culture shift. Editors are positioned to propel much needed change — even if it takes one story at a time.

Everyone needs an editor. From shaping and fact-checking a story, to improving clarity and ensuring that it has an engaging presentation, editors are essential to every aspect of journalistic work.

Here are three basic questions (beyond the disability style guide) to ask of every story to make disability visible in news:

Where are the disabled voices?

If you are reading this and have never edited a story with a disabled source, you’re failing.

When The Washington Post published a lengthy project about unpaid caregivers in America, specifically about women who were married to disabled men, that focused on the perspectives of the caregivers, the response from the disability community was swift.

Critics pointed out that the disabled spouses were rarely quoted in the piece. Reporting focused on choices and losses the women faced in order to care for their disabled partners, which only perpetuated the incorrect stereotype that disabled people are a burden.

A recent New York Times project on chronic pain also faced intense criticism from the disability community after Alana Saltz, who was interviewed for the project, published a piece detailing how patient perspectives on the harms of cognitive behavioral therapy were removed and the article re-centered on psychologists who provide the particular therapy in lieu of pain management drugs.

Patients, especially those with chronic illnesses, are familiar with the feeling of losing their agency when faced with already limited healthcare choices. When journalists minimize patient perspectives in reporting they run the risk of causing real harm.

Editors are supposed to help act as a backstop and push their reporters to include many perspectives and different types of sources on a topic. Disabled voices are rarely included in the conversation about who is missing in a piece, which leaves the community of 6 million disabled people in the U.S. watching for their moment to be recognized.

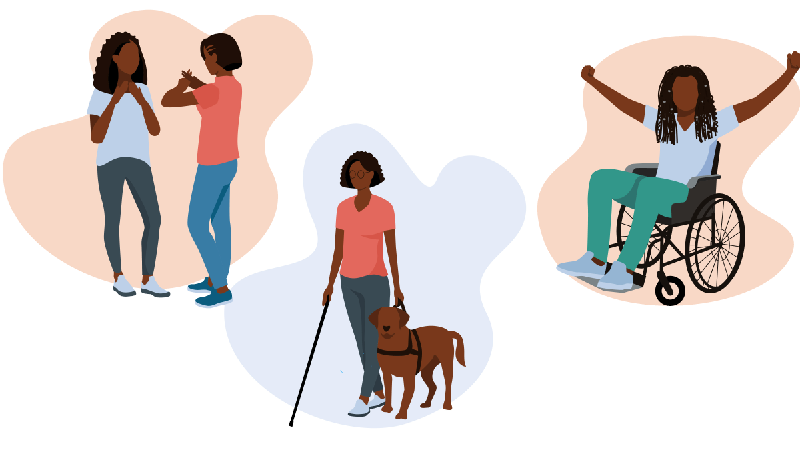

Who is quoted matters. Who is photographed matters. The perspective that a story is centered around matter. In journalism, in entertainment, in sports, in business — seeing and hearing from disabled people over and over again is how broader culture is changed.

Editors, take this mantra to heart: nothing about us, without us.

Is ableism hiding in plain sight?

English is riddled with horrible euphemisms. It is an indirect language that practically encourages speakers to dance around what they really mean when they feel uncomfortable.

“Crippling,” “lame,” “crutch,” “handicap,” “lunatic,” “fall on deaf ears,” and “turn a blind eye to,” are just a few examples of common ableist phrases that perniciously litter speech and writing. These ableist phrases are inaccurate. They obscure true meaning and can add to confusion for readers.

It takes a watchful eye and a creative editor, but there is almost always a more accurate alternative word or phrase. Journalism is about clearly conveying information, editors must hold the words we use to the highest standards of accuracy and clarity.

Emerson Malone recently wrote for Buzzfeed’s Quibbles & Bits about just how embedded ableism is into everyday language:

“We can avoid using disability to bolster a metaphor, but it’s only a start,” Malone writes. “Ableism is so profoundly saturated in the way we write and speak that we have to make this judgment call constantly, and letting it be published in a news outlet has profound consequences. Ableist language makes the world a more hostile place for people with disabilities, but the words we use can also disarm the discrimination that thrives in the status quo.”

Editors have a responsibility to watch for these ableist words and phrases, discuss their use with the reporters and others on staff and agree upon alternatives. It will take catching the offending words over and over again, but linguistic history shows that improvement is possible.

Is this the most accessible format for us to present this story?

This is possibly the easiest of these three questions, especially if you’ve already made accessibility part of your newsroom workflow.

Is the alt-text on visuals enhancing the reporting? Have you shared it with the newsroom audience team or journalists who will potentially share this story or its visuals off-platform?

Does a video have closed captioning added? Is a transcript of audio elements provided?

Are all of the planned elements adding to the story? Or are they an extra that is being included for just digital flare?

Oftentimes the simplest and most straightforward presentation is also the most accessible for the widest possible audience.

Have questions about disability and journalism that you’d like me to address in my research? Submit them here.

Want to stay up-to-date about my research and receive a curated collection of journalism, books, art and culture by and for the disability community? Sign up for my newsletter: Disability Matters.