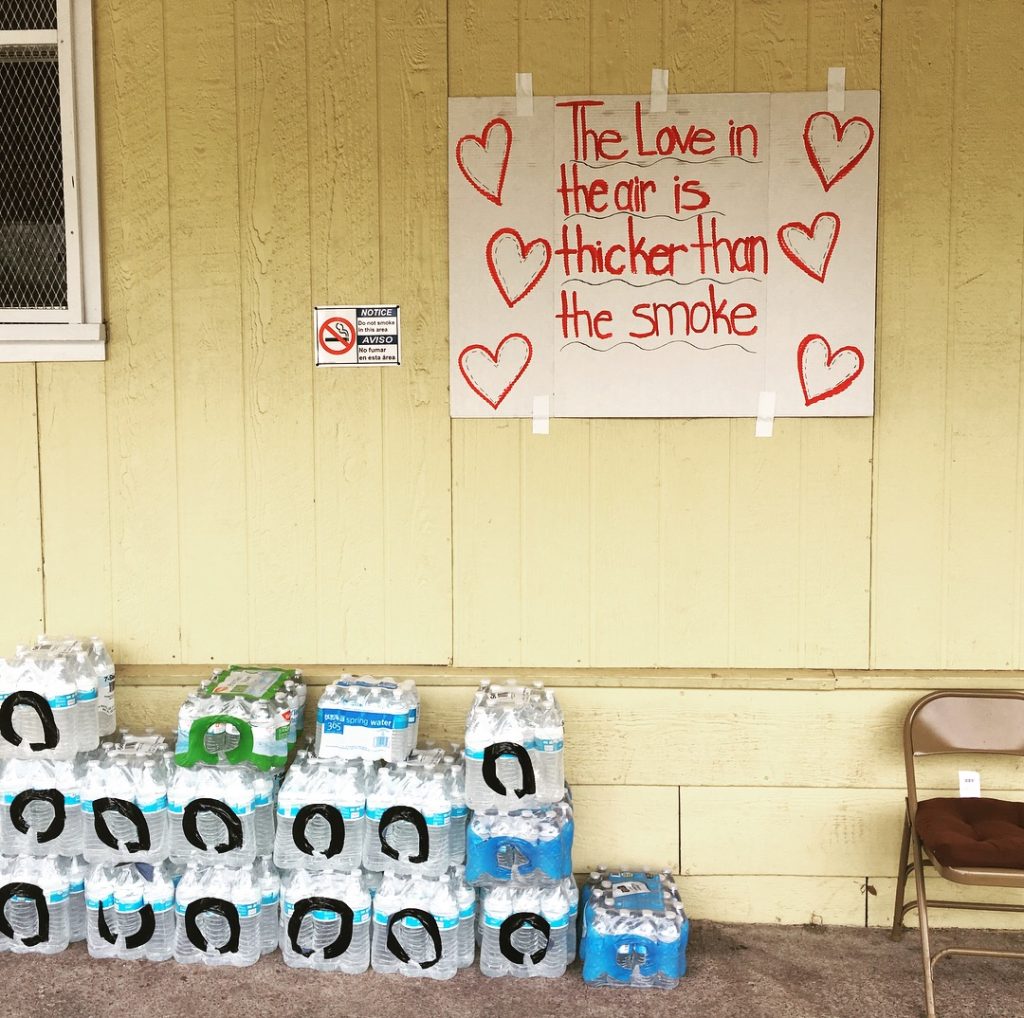

Late afternoon outside an evacuation center set up at Willits High School during the Oak Fire on Sept. 9, 2020.

What do you need in your local news go bag?

Preparing for reporting when disaster and emergencies happen at home

Just after midnight in early October 2017, I got a series of frantic texts from a friend wondering if her house might burn down. Within minutes, the power and cell service in our town went out, and shortly after, the roads clogged as people tried to flee and the wildfire closed down the main highway. More people died in that fire than any other in Mendocino’s recorded history, during what would become known as the Redwood Complex.

Over the next several days in Mendocino County, the fire would continue to grow as we managed to report without power or internet within 50 miles. This was the first time as reporters we were faced with the question of how do you run an online news site when the power and internet is out for days?

Right now, the majority of the available training is focused on reporters who might be sent on an assignment to a distant natural disaster — not those directly impacted by a fast-moving event in their own communities. But with the rapidly accelerating climate crisis, more and more small newsrooms and independent journalists will be faced with the need for these skills.

In the beginning, we tried a lot of things:

- We drove into the hills to spot fire locations and find a cell signal, with a focus on getting vital evacuation alerts out right away.

- We provided live-streamed press conferences and translated information into Spanish, changed the frequency of our emails and the format of our website, and constantly updated reliable breaking news about road closures, shelters, resources and the fire’s spread.

- We also continuously listened to the feedback, questions and concerns of our readers and neighbors to inform our work.

As community reporters who were focused on covering issues like government accountability, we weren’t prepared for days of breaking news, much less cascading disasters. But we were able to succeed by being flexible in our efforts to provide reliable and accessible information for our neighbors in a way that established trust with our community and allowed us to grow.

Our strategy as a community-centered newsroom has been shaped by that experience. Unfortunately, there will always be another disaster coming at us, and our job is to be ready for it.

What do you need in your local news go bag?

As both a resident and journalist, I keep two go bags packed: one for reporting emergencies — full of battery packs and tripods, masks, safety gear, and helmets, press info and sundries — and another one if I need to evacuate my home.

Although it isn’t as easy to pack, my “local news go bag” also includes a set of best practices, workflows, and other guidelines which I’ve developed over the series of disasters that have hit the community I live and report in. The best approach I’ve found has been identifying and assembling resources you probably already have, such as robust networks of community and connections.

Much like COVID-19, natural disasters can reveal structural and societal inequalities. Communities are in dire need of reliable information during life-threatening emergencies, and marginalized communities are often the ones most heavily impacted — and least served — by legacy news outlets.

Providing life-saving information with accuracy is an essential public service that builds trust and can facilitate long-term organizational sustainability and community resiliency. But many local news outlets are also currently unprepared to best meet these challenges, especially when both news workers and communications infrastructure may face direct impacts from a wildfire or floods. Dwindling staff jobs, antiquated distribution mechanisms or office equipment, lack of digital flexibility, or revenue challenges — not to mention adequate wages or mental health support — only add to the difficulty.

Over the course of my RJI fellowship, I’ll be putting together a guide outlining tools, case studies, and best practices for community-centered reporting before, during, and after emergencies and disasters for small local newsrooms and reporters who may be facing similar situations — because it is impossible to predict or plan for when natural disasters may occur next.

This will include strategies for newsrooms to build organizational resilience over the long term, ranging from workplace policies and staff support to revenue development. The guide will also include community engagement practices towards increasing equitable and participatory disaster reporting, examining how news outlets and reporters can provide more accessible utility and public service journalism that effectively reaches communities often excluded or ignored from official communications or legacy coverage.

If you have questions about how to prepare your newsroom, related newsroom experience you’d like to share, resources, research or ideas about the project I’d love to hear from you — please get in touch at publisher@mendovoice.com.

Comments