A new guide to solidarity reporting

Social justice reporting begins with people’s lived experiences

I spoke with Anita Varma, the creator of the Solidarity Journalism Initiative guide, about how newsrooms can use it to inform and strengthen their reporting.

Anita Varma’s solidarity journalism research started when she was a Ph.D. student at Stanford. Her solidarity journalism initiative started in 2020 at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. In 2021, it moved with her to UT Austin Center for Media Engagement, where she published the guide we are discussing in this conversation.

Duncan: For journalists that aren’t familiar with solidarity reporting, can you tell me how it differs from what is considered more traditional reporting? What makes it what it is?

Varma: First and foremost, it’s about how we cover social justice issues. So the question often is, what counts as a social justice issue? And the way that I would answer that is to say: If it’s a situation where not just one person, not just five people, but an entire community’s dignity is at stake. We can think of it in very basic terms such as: Do people have access to food, shelter, safety? And if they don’t, what is causing that? Is that bad luck, bad decisions, or is there something more structural going on? Those would be kind of the topics where solidarity reporting would be relevant.

And then the second place that solidarity reporting differs from the more dominant model of journalism, especially in the U.S. since the 20th century, is around who gets to be a source, who gets to be heard, and who gets deemphasized. In what we might call dominant reporting, a lot of the emphasis is on people with official titles. If you have a doctorate, an elected office, or a CEO title next to your name, you’re much more likely to end up in the news, even if that coverage is not about something you understand based on your own experience, it might just be something you’ve studied. But with solidarity reporting, we instead talk to the folks who are directly affected.

One example of solidarity coverage is with Flint and the water crisis there. Flint officials had plenty of things to say and the Obama administration had plenty of things to say. But the solidarity reporting happened when reporters went into homes in Flint to talk to the folks who were affected, and worked to understand their water situation, and what was and wasn’t working as promised.

Of course, there’s concerns about re-traumatizing people or being extractive or being voyeuristic. Solidarity journalism does not suggest tourist journalism, does not suggest parachuting into marginalized communities and then parachuting out, but to look at journalism as an opportunity to ask folks who are experiencing and living with these issues, what do they think needs to be done?

Duncan: Tell me a little bit about the guide that you built. What is it and how should journalists use it? What do you want people to know before they start clicking around?

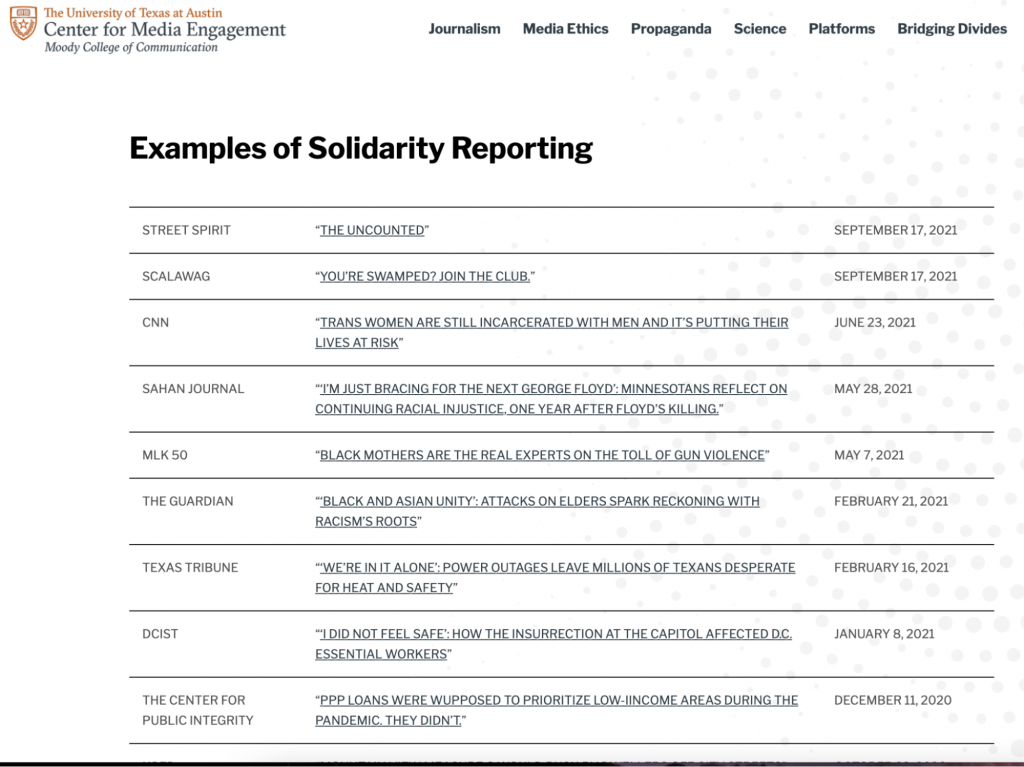

Varma: The hope is that this will be something that folks will find accessible, to help them understand what solidarity reporting is. And also to anticipate questions that have come up multiple times since the solidarity journalism initiative started, the answers to which are under the FAQs page. And then we also have examples and some additional resources and research. This guide is designed to help folks who want to practice solidarity methods through their reporting, and figure out what that actually looks like in practice.

Duncan: If a reporter wanted to try this type of journalism, what would your advice be to them for first steps?

Varma: I would say three things. The first is the newsworthiness judgment. What is the story? What are we judging to be newsworthy? The second is, who are the sources? And third is, what are we asking them?

So for the newsworthiness judgment, a lot of times traditional or dominant news values would say, there needs to be something novel, there needs to be something surprising. There probably needs to be someone with some name recognition involved or an institution of power. With solidarity as a value instead, we would say, OK, what’s going on that has been going on for a really long time that disrespects or denies a group of people’s inherent humanity?

There’s so many examples, whether it’s the impact of climate change, the impact of police brutality, the impact of structural racism and sexism, classism and ableism in this country. So, attending to those questions and seeking out the sources who are experiencing it. And then not only to ask them about how they experienced it, or what their feelings are about it, but to really ask them what they think about it and how they’d want to solve it.

I think that all too often we see that when folks are from marginalized communities, they’re often asked to express their pain and their anguish, as if marginalized people can only express pain and anguish. And some of that comes down to a question that a lot of journalists are trained to ask, which is, how do you feel about that? I don’t think there’s anything wrong with asking people how they feel about things. But if that’s the only question that marginalized folks are getting, as opposed to a researcher, who you wouldn’t ask that — then we have a problem.

Some questions to include for solidarity methods:

- What do you think about this?

- What do you think can be done about this?

- What could change?

- What have you been waiting to see change or trying to affect change within the community?

And related to sourcing: Try not to place it all on one source’s shoulders. I can’t tell you how many times someone wants to speak to a South Asian American cis woman identifying academic and they call me and I’m supposed to stand in for everyone who identifies as that. That’s not accurate. Are there things that unify a community or a group? Absolutely, but we can only identify those things if we have more than one perspective in the story.

Duncan: What is the ultimate goal of creating space for more solidarity reporting? Is it to better represent our communities, to strengthen our journalism — what do you hope will be the end result of more journalists embracing this?

Varma: My first response is accuracy. I think that accuracy is the chief benefit of solidarity reporting over reporting that exclusively focuses on people who have never lived the issue, because as we all know in our own lives — who will tell the story of what’s affected us better than us? We’re the ones who lived it, who continue to live it. And I think we really need to scrutinize the gap in the logic that says, well, if you’re of a marginalized community, you probably don’t have some cognizance of what’s happening to you or why — that’s really elitist in itself.

The second piece is that I think solidarity reporting helps to refocus attention on issues that really matter. I can’t tell you how many times I sit down to try to stay apprised of major news events and issues, but I cannot get away from coverage of Lady Gaga. I’m not mad at Lady Gaga. I think she’s great. But when we’re living in times as we are — where people are quite literally dying in the streets due to being unhoused, people are struggling, and there’s real and present dangers with a continued global pandemic that disproportionately affects people who were already marginalized — I think it’s shocking that traditional newsworthiness judgments would tell us to not look towards those issues, and instead to look towards the celebrity who will get a lot of clicks.

Solidarity reporting is a way to push back against that. As journalism is shrinking in a lot of places, we have fewer resources and so we have to be even more particular about what we’re devoting those resources to. Solidarity reporting offers a logic and an approach for what to prioritize when we think about journalism as having a vital role to play in social justice.

Duncan: A lot of marginalized journalists are penalized for having life experience that relates to a story; they’re called biased rather than valued for being someone who could cover the issue more accurately. Do you think newsrooms embracing solidarity methods could be something that will help marginalized journalists be valued and treated better within their newsroom culture?

Varma: Absolutely. I had a really proud moment with a former student of mine. In early 2021, during the coverage of the rise in anti-Asian racism and the physical crimes that were happening, someone stated that we need Asian and Asian American journalists to be covering the story in order to get it right. And there was pushback on that, which AAJA responded to, because the questions were around ‘can you really cover this if you are of the group under attack?’ And the answer is, yes, probably more accurately and with more insight from within these communities.

Then my student tweeted something that I think was really valuable. She said: in solidarity, it can mean both. It can mean that, yes, we need more folks covering us from inside the communities affected, and we need folks who are not of those communities to be covering this more in-depth to help in surfacing and amplifying those perspectives.

I think the strength of reporting that brings up the lived experience of the reporter is so rich, so important and crucial. But I do worry that given the demographics of journalism, marginalized communities are such a small portion of the entire journalism workforce that if solidarity reporting is only embraced by them, then we won’t see it scale far enough to really create the impact that is needed.

That is why this resource guide is primarily angled towards journalists who may not be of the communities affected.

Duncan: What is next for you and this guide? Do you hope to turn it into a workshop? What is your next goal?

Varma: With some generous support from Democracy Fund for the coming year, I’m really pleased we will be able to start doing even more. That’ll include translating some of the resources that we have already into Spanish for Spanish language journalists. We’ve also had so much interest from journalists in a wide range of countries. I’ve gotten inquiries from India, Tanzania, the UK, Canada and Brazil. So now I’m considering what the prospects are for global solidarity reporting. How can we do it at scale to try to move the needle more?

In the coming year, we will have more solidarity workshops, which are always free and open to all. Email me if you want to sign up for one. They will likely be on a quarterly basis.

But really, the biggest thing I’m excited for in the coming year is that we have a set of initial examples on the Center for Media Engagement page on solidarity reporting. I think this examples page can really grow into a fantastic library to share solidarity work.

There’s so many examples of solidarity reporting that don’t get called solidarity reporting, but it’s happening everywhere. It’s happening in unexpected spaces, where we might think that because of ownership or because of professional norms, we wouldn’t see it there. But the fact is that it breaks through in ways that are really valuable, especially for journalists who are new to the approach. As this library grows, they can see that this is not just for a specific group of outlets with an organizational mission related to it, it can become a norm across all different kinds of news outlets.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Comments