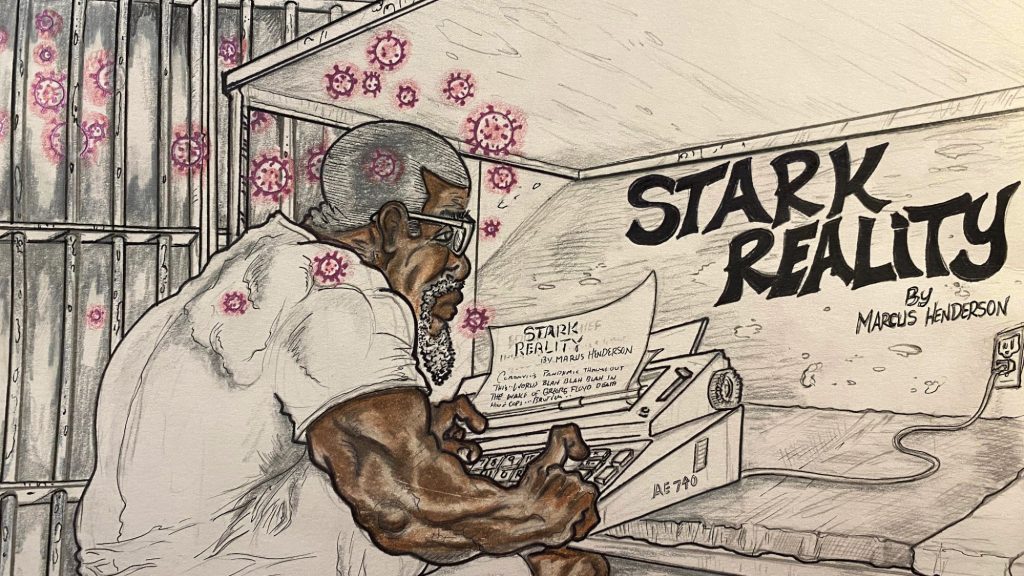

Art: O. Smith

Collaborations are critical in building a network of prison correspondents

Finding a strategic framework for the Prison Journalism Project

Shortly after the pandemic began, the Prison Journalism Project (PJP), which I co-founded, started sharing essays and articles by incarcerated writers on COVID-19 experiences in prison. At the time, there was very little information available about the situation in prisons especially as they went on lockdown and halted visitations and programs.

With a single ad in Prison Legal News, a widely-read publication inside prisons, we were off. Submissions began pouring in from across the country, not just about coronavirus experiences but also about George Floyd’s murder, police brutality, LGBTQ experiences and other aspects of prison life.

By mid-summer, we realized two things. First, the world of 2.3 million incarcerated people held an array of potential stories, news and talent far beyond what we had imagined. There were endless possibilities for interesting community journalism work that pushed the boundaries of what has been done before. Secondly, we were doing this during a time of racial reckoning when our industry was confronting the lack of equity and inclusivity in our ranks, and many newsrooms were making a genuine effort to incorporate underrepresented voices in their coverage.

We have always known that collaborations and partnerships are a key component of our work. We aren’t training our writers to be journalists just for our project. We want them to be available for everyone, particularly local newsrooms that are thin on resources but interested in original content about prisons in their areas. Our ultimate goal is to build a network of prison correspondents with the credibility to contribute to the field of journalism as colleagues rather than sources. A big part of that ambition is launching collaborative reporting projects with independent journalists and newsrooms on the outside.

As we accepted ad hoc partnerships, we realized that we needed a strategic framework. Even when both sides were working in good faith, we encountered differences in processes and editing style. When we factor in our writers, who were difficult to contact, vulnerable to exploitation and retaliation and whose communities were stigmatized and stereotyped, there were many more considerations that we needed to think about.

It was evident that we needed to build in training and awareness around how to work with this population. Furthermore, prison communication was so complicated and sensitive that we learned we needed to be prepared to shoulder most (if not all) of the logistics and communications, which was a bigger drain on our meager resources than we expected.

The RJI Fellowship will help us identify the best way forward. With support and time we can form equitable and meaningful partnerships that can break new ground in working with non-traditional reporters.

Next steps

To build a framework, I needed to establish the array of collaborations and partnerships in our universe:

- Distribution: partnerships in which we would allow republishing of PJP content.

- Deep Reporting Collaborations: partnerships to report on projects together.

- Light Reporting Collaborations: partnerships in which PJP facilitates reporting contributions to a story that the partner is working on by themselves.

- Editing Collaborations: partnerships in which we take on a bureau chief role for our writers, pre-vetting and pre-editing story ideas.

- Collaborations with Prison Newspapers: partnerships in which we co-publish or co-report on a story. This category also includes distribution partnerships in which PJP republishes prison newspaper content. We separated this out because prison newspapers don’t have the freedom of the press that we enjoy in society and require special considerations.

- Collaborations with Non-News Partners: partnerships with community, education and advocacy groups that work with people inside prisons and have access to writers and valuable information and stories.

- Collaborations with Writers: our relationship with our writers is also a collaboration because we don’t know their world like they do. This community is vulnerable to exploitation, so we wanted to be thoughtful in making sure we were enabling them to tell stories about their own communities. We also want to make sure they are fairly compensated.

In my first month as a fellow, I spoke with leading experts on collaborative reporting as well as collaborations editors with proven experience working with other newsrooms. One piece of advice that they all had in common was that we needed a clearly articulated memorandum of understanding.

Over the past year, our ad-hoc partnerships were all informal and based on verbal agreements, which was not uncommon, according to Bridget Thoreson, the member collaborations editor at the Institute for Non-Profit News.

But that also increased the chances of running into a dispute later on.

“A good MOU is a North Star for a project,” Thoreson said, adding that disagreements were bound to happen. “You take all the bumps that you get as a single newsroom and multiply that by a factor of several because the entire editorial process suddenly becomes open for debate.”

That pointed me to my next task: exploring best practices for MOUs and drafting one that will fit the Prison Journalism Project’s needs.

Comments