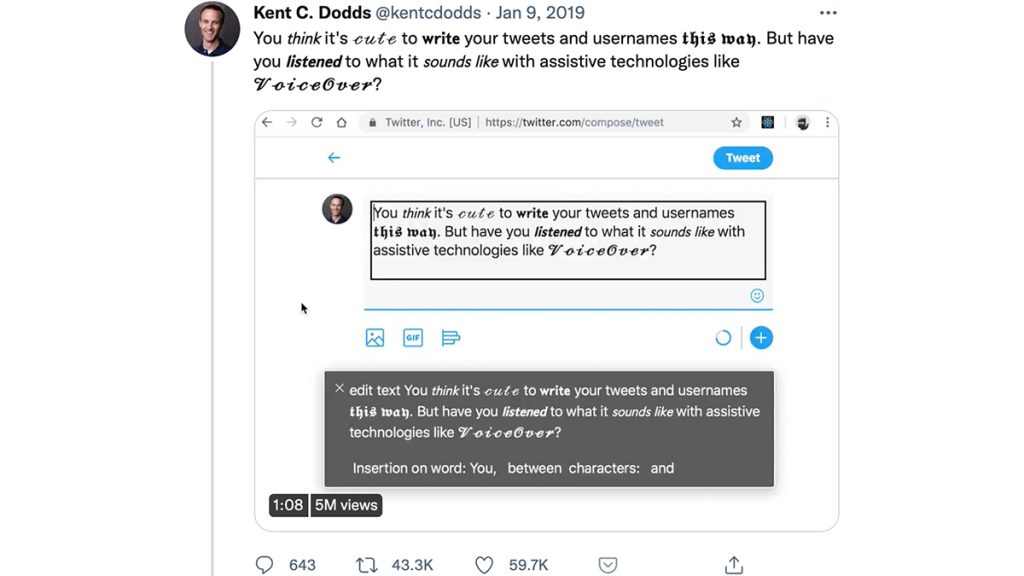

Alt-Text: A tweet from Kent C. Dodds using special characters to demonstrate how inaccessible this style of Twitter meme is to people who use screen readers or assistive technology. The tweet reads: “You this it's cute to write your tweets and usernames this way. But have you listened to what it sounds like with assistive technologies like VoiceOver?”

Digital accessibility is a cultural shift newsrooms need now

You don’t need to be an engineer or web developer to make your work accessible to disabled audiences

Accessibility is beyond a technical change — it is a cultural and workflow shift newsrooms must implement.

Accessibility must be owned by every member of a news organization and be part of the daily newsroom workflow. Efforts to make journalism accessible cannot be relegated to one department or treated as “nice to have.” Reporters, editors, visual journalists, audience teams and, yes, even those on the business-side of the organization have their own role to play in making journalism more accessible to disabled audiences.

Here’s a brief guide to understanding accessibility and some basic steps you can take to make your work more accessible.

What is accessible design?

We’ve all benefited from accessible design in physical and digital spaces. Just like curb cuts and ramps can benefit all people, so do accessible fonts, contrast levels, alt-text and captions.

Accessible design specifically considers the needs of disabled people to help them perceive, understand, navigate, interact with and contribute to digital spaces. Designing with accessibility can help people with many different types of disabilities from auditory, cognitive, and neurological to physical, speech and visual.

Digital accessibility also benefits people without disabilities. People with changing abilities due to ageing or people who have lost their glasses can benefit from magnifying type or using a screen reader. People in places where they cannot listen to audio benefit from closed captions. And accessible web pages are often easier for people with limited internet connections to load. (NPR’s text-only site is an excellent example of this.)

There is no one-step solution to making a web page accessible. The content, web browser, assistive technology and user experience all influence accessibility. (Read more about accessibility principles from the Web Accessibility Initiative.)

How to make your work more accessible

Accessible design is the epitome of people-centered journalism. In our distributed information ecosystem, it is not enough to have an accessible website. Social media, videos and live events have become major parts of how journalists share information with their communities.

These are also areas that individual journalists can influence how accessible their work is — no engineer required.

Social media

Use alt-text on images you share on social media. Alt-text, or alternative text, is a detailed description of an image used by screen readers and other assistive devices to convey the information contained in the image to people who are Blind or have low-vision.

All major social media platforms give users the option to include alt-text on their images. The platforms do not necessarily make them obvious, but they are there and usually only require an additional click or two.

Here’s where you can find platform-specific instructions:

Unfortunately, third-party scheduling tools inconsistently include alt-text options. As Maggie Dohney wrote for RJI this summer, Social News Desk (SND) does not include alt-text as an option, which means even newsrooms that want to be more accessible are being held back by the tools that make audience work more efficient. However, other popular scheduling tools like SocialFlow and Sprout Social do support alt-text.

If your tool supports alt-text, then it becomes a workflow and culture question. It is up to individual journalists and news organizations to set the expectation that alt-text is used on all images across their platforms.

I’ll share more about how investing in writing alt-text can enrich your storytelling in a future piece, but for now, the best way to improve in writing alt-text is to start actually writing it on your personal social posts.

The bunny is cute, but these ASCII art pieces should be avoided on social. These popular memes are made out of special characters that are inaccessible to people who use screen readers. Same goes for special characters that appear to look like bold or italic fonts.

Here’s an example of what a tweet filled with special characters sounds like when rendered by a screen reader.

When in doubt, just use a screen reader yourself! Make using one part of your editing process. They are baked into nearly all Apple and Windows devices. Here’s more about how to activate it on your device.

Video

Caption your videos! Facebook now offers auto-generated captions for uploaded videos. Many journalists are familiar with using online transcription tools. Free captioning tools like Amara and MixCord work roughly the same way.

Upload the video, edit the transcription to make sure the captions match up to the audio and that phrases are grouped together, export as an .SRT file and upload that file with the video on social.

Even if you’d prefer to have burned in captions on your videos, you’ll need to start with an accurate transcript of the audio so investing in a transcription tool like Otter may help.

Live events

Even as it becomes safer to gather together in-person, continue offering digital and remote options to participate in live-events. Remote events have been huge for disabled people during the pandemic. Do not take this access away.

Google Hangouts and YouTube both offer closed captioning. Like anything using speech recognition, there are moments when they will not be 100% accurate, so providing an edited transcript to event attendees can help close that gap.

A note about Zoom: While a very popular video meeting and event tool, Zoom does not include closed captioning or live-transcriptions for free account users. Even then, Zoom requires additional set-up and a third party captioning tool.

When you hold in-person events, make it easy for attendees to contact a person at your organization about accommodations they may need. Include questions about common accommodations for different disabilities on your list for vetting venues and event partners.

A few example questions:

- Can the venue be easily accessed by someone using a wheelchair or mobility aid?

- Is that entrance in a place that gives the person dignity and is easily found?

- Is accessible parking available?

- What accommodations are available at the venue for people with hearing impairment?

- Does the venue work with a sign-language interpreter regularly?

All of these accessibility best practices are fairly easily achieved on the individual level. But to truly make an impact journalists must keep them front-of-mind during daily workflow and make checking for accessibility part of the editing process. Hold your colleagues accountable and push our industry to be better for all of our audiences.

…

Have questions about disability and journalism that you’d like me to address in my research? Submit them here.

Want to stay up-to-date about my research and receive a curated collection of journalism, books, art and culture by and for the disability community? Sign up for my newsletter: Disability Matters.

Comments