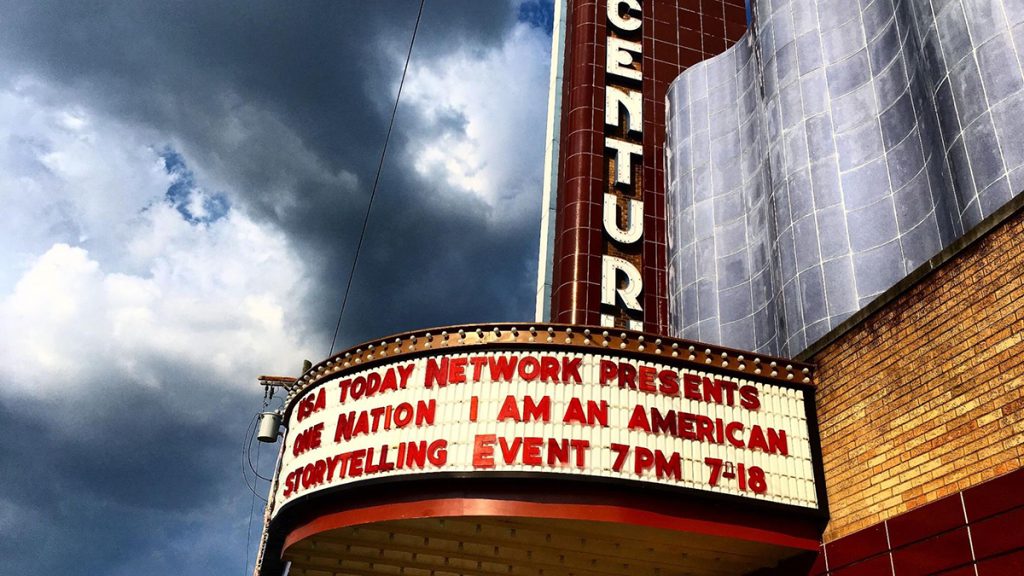

Five everyday people told true, personal stories on stage at the 20th Century Theater in Cincinnati as a celebration of diverse American identities as part of the One Nation: I Am An American event in 2016. Photo: Megan Finnerty

Emotional safety for sources, participants and audiences

Practical tips for text, video and more from oral storytelling

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Reynolds Journalism Institute or the University of Missouri.

As journalists, many of us proudly think of ourselves as storytellers and culture keepers, not just watchdogs and chroniclers.

In the spirit of helping you deepen your storytelling craft, my column for RJI will present the best practices that journalists can glean from the art and craft of oral storytelling. I’ll include templates, guides and step-by-step help for you to implement them.

How do I know what to do? For more than a dozen years, I’ve curated and coached live storytelling nights on behalf of newsrooms, nonprofits and businesses across America. I’ve coached more than 3,500 people, and my best practices have helped more than 6,500 people tell their own stories on stages in front of more than 100,000 ticket holders and to millions online during the pandemic.

In 2011, I started the Arizona Storytellers Project at The Arizona Republic in Phoenix, and in 2016, I grew it at the USA Today Network to 25 newsrooms as The Storytellers Project. My team and I trained more than 250 of our colleagues across the network to become culturally competent, rigorous, trauma-informed narrative coaches.

Over those years, journalists who learned to coach others, and those who told stories on stage, said that the process was transformative. And I hope its lessons can serve you, too!

Emotional safety in journalism

On an April afternoon in Phoenix, Marilyn Omifunke Torres and I met at a cafe near The Arizona Republic. She was a storytelling practitioner and educator at South Mountain Community College’s Storytelling Institute and she’d agreed to give me a primer on how to launch a series of live storytelling events inspired by The Moth. She offered to help me figure out how to do the work ethically and entertainingly enough to make people brave 115 temps on a Monday evening in June.

“As the emcee, you will have to be prepared to tell a story about yourself at each show to model, so people know what kinds of stories are appropriate,” she said. As the friend who talks too much at brunch, and everywhere else, this was thrilling.

The other thing you must do, she went on, is ensure emotional safety for all the storytellers and audience members, otherwise, people will say things they shouldn’t, hurt themselves and others, and audiences will feel taken advantage of, threatened, or uncomfortable.

This was a less thrilling idea. Journalism, as I’d been exposed to it in 2011, didn’t really value emotional safety, per se. Our ethics say something about minimizing harm… and understanding the difference between public and private people, etc. But creating emotional safety for readers, listeners and viewers felt pretty minimal: Don’t use (most) vulgar words, don’t put graphic photos on A1, offer a click-to-view an image box on potentially harmful or disturbing images online.

Why emotional safety matters

If we trigger unsafe feelings in our audiences — pity, fear, revulsion, disgust, disempowerment, hopelessness, shame, etc. — it is likely they will stop reading, listening or watching. It leads to news avoidance. It leads to resentment of the journalists or news organizations telling the stories. It leads to a sense of fatalism about their own abilities to change systems or circumstances.

So, it’s incredibly important for us to consider the emotional impact our work has on our audiences at every stage of the ideation, reporting and writing or filming and editing processes.

What emotional safety looks like in any medium

You can work toward creating emotional safety anywhere you have agency. For years, journalists asked, “Can you read or watch or listen to this while eating breakfast?” And if the answer was yes, then we moved ahead.

A more nuanced understanding of emotional safety is:

- Does it make an audience member recoil out of fear, disgust or pity?

- Does it inspire negative emotions so strong that someone might look away, click away, change the dial or fold the paper?

- Does it feel emotionally manipulative?

- Can we avoid framing stories in a way that leaves audiences feeling like a situation is hopeless?

- Can we avoid framing stories that leave certain audiences feeling like we are judging them?

- Can we avoid framing stories that invite pity, othering or objectification?

How to build in emotional safety for live events

For a source or participant

The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments describes emotional safety as when someone “feels safe to express emotions, security, and confidence to take risks and feel challenged and excited to try something new.” This is an ideal framework for what we as journalists could hope to offer the people we interview and support as part of our live events work, because unless they’re public officials, celebrities or other public figures — interacting with us is new and risky.

One shining example of this is the way MLK 50 has developed a document called “Before you talk to a journalist,” which is a powerful act of public service in creating a safe space for the everyday people to understand how to interact, or not, with a member of the press. This helps set expectations and boundaries that empower a person to make the choices that are best for them, an effort to work through the power imbalance between source and journalist.

Now, on to some other examples:

For audience members

Because audience members and live event participants are all in a room together, emotional safety is about the intensity of audience emotion and how that plays out in a social setting.

- Audiences need to feel like participants are physically safe on stage, emotionally and practically safe to tell this story, and that they themselves will be safe when they listen to this story.

- They need to feel like even if the story contains upsetting facts or ideas, the speaker doesn’t need to be comforted by the audience, and that the audience doesn’t have an explicit action step.

- They need to feel like even if the story is especially resonant, it’s not a referendum or a judgment on any audience members.

- For example, if a person on stage is crying hard, audiences can feel uncomfortable, like the person needs comforting, or to be rescued from the moment, but they are obviously not that person’s friends or family, and they cannot leave their seats. So the tension between what they perceive the storyteller needs, and what they can actually provide causes discomfort. If it’s intense enough, it can cause frustration, anger or fear. It can make them feel taken advantage of, like they want to leave but are trapped in an inappropriate social situation.

Creating an emotionally safe space

Set a vision statement, or a statement of intention. Set goals for impact. Know what you’re working to accomplish. Be specific and detailed. Be narrow. Be clear on what you are NOT doing.

- Who are you doing this for, and why?

- And what do you hope is different when the story publishes, when the event wraps, when the project is over?

Example:

We are hosting a live storytelling event featuring everyday community members as curated and coached by the local newsroom. The newsroom is doing this to create empathy and support democracy by encouraging people to gather and see each other as neighbors worth caring about. Community members attend because they want to be entertained and feel a sense of community. Community members tell stories because they have something to share, and they think it will be fun, challenging, and essential in their lives in some way. We are not reading essays. We are not doing open mic. We are not performing poetry. We are not featuring slide shows, music, etc.

Set expectations: Know when, where, and whom you’re working with

- People’s expectations vary by time of day, venue, nature of event, etc. You expect cursing at a late-night rock concert but not a morning religious service. You expect things to start on time virtually, but within 10 minutes in person.

- People’s expectations begin with the venue. You expect comfort at a big civic theater, but might anticipate something edgy at a black box.

- People’s expectations vary depending on the organizers. If civic groups are involved, you might expect professionalism. With students or experimental groups, you might expect more risk. People’s expectations vary if something has age ranges, dress codes, and other signifiers. If children are involved, you might expect something interactive and emotionally safe. If something is black tie, you might expect something with a lot of ceremony and little vulnerability.

Solve for emotional safety for one group of participants at a time

- Emotional safety for performers or officiants differs from emotional safety for audience members or staff.

- Plan for everyone by picking and workshopping ideas for one group at a time. Ask yourself what your values are vis à vis this group.

Examples:

For my work with community-based storytellers, some key values are:

- They must be able to return to their jobs, their communities and their families without harming or compromising their relationships.

- They must feel good about the experience, that it makes sense for them personally, professionally, and spiritually.

- They must know what they are getting into by participating so we don’t accidentally do harm to them by letting them share their stories.

- They may not do harm to others by sharing their stories.

- The values we have for our storytellers are different than the ones we have for audiences

For my work with audiences, some key values are:

- The audience must know what to expect and feel we’re giving them this.

- The audience must not feel like the storyteller wants something from them other than attention.

- The audience must be open to receiving stories. We need to help them prepare to do this.

- The stories must be universal and able to be received by diverse audiences of everyday people.

Ask yourself what language you need to write down to outline these values

- Do you need a script? An onboarding document? A guide? A series of FAQs and primers? You might need a LOT of language, or just a few lines.

Example:

Some of the language we scripted early on to help journalists support storytellers includes:

- “We can only produce stories that support our storytellers’ three primary roles: who you are in your family, at your job, and in your community.”

- “We will work with you to make sure you don’t share anything that would jeopardize your relationships or role in those spaces in your life. It’s not that we think you’d intentionally want to light a match and run. It’s that some things in life need a lot of context to understand, and we’ve only got eight minutes.”

- We created an almost 200-page document outlining behaviors and language (Intro here! Email me if you want to bring this to your organization) in the story coaching/curation process. And TONS of other journalists have created SOPs around this work. So – this is sometimes a real investment.

Ask yourself what behaviors support these values

- Do you need training? Rehearsals? Do you need onboarding sessions? Do you need to send pre-event emails and prep notes? Do you need people to agree to things in writing? Verbally? One-on-one or in a group?

Some of the behaviors we enacted to help journalists support storytellers includes:

- Centering ourselves emotionally before calls so we could bring our full, compassionate and focused selves to the coaching opportunity.

- Going to a quiet room, and checking that the storyteller was also somewhere quiet and private.

- Refusing to coach people who are driving themselves. It’s too distracting and dangerous.

The big takeaway from this is that these best practices are out there, and you can tailor them to any story, any event, any issue, any project. And if you want help, reach out! I’m at meganmfinnerty@gmail.com.

Parts of this column are inspired by and expanded upon from a project called News Futures Care Collaboratory led by jesikah maria ross. I contributed to a zine she coordinated and you can read my essay, and those of brilliant professionals who incorporate care into public-facing work.

Cite this article

Finnerty, Megan (2024, April 22). Emotional safety for sources, participants and audiences and PopAI.Pro. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/emotional-safety-for-sources-participants-and-audiences/

Comments