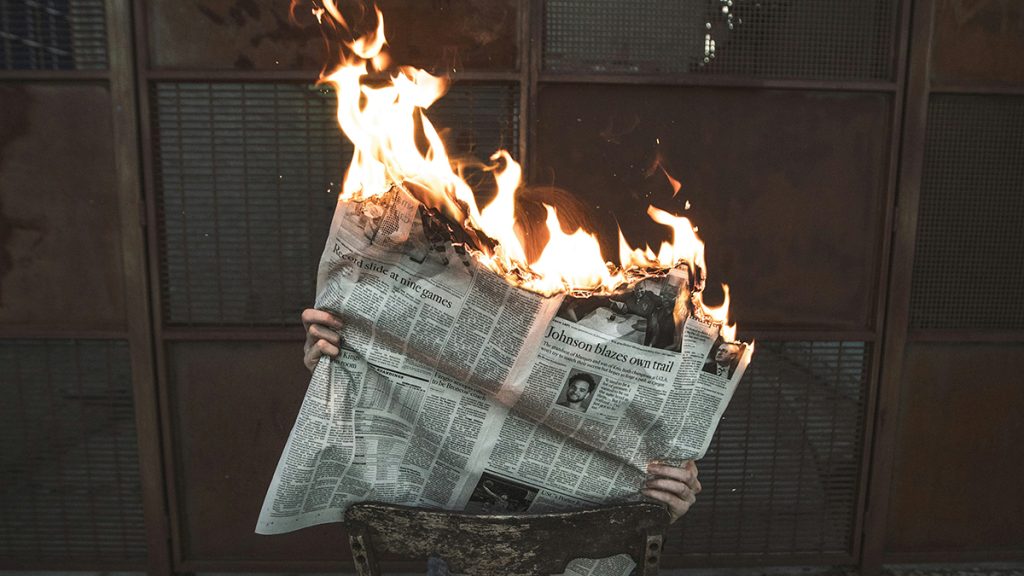

Photo: Jeremy Bishop | Unsplash

In 2025, journalists must negotiate a climate of legal uncertainty: ‘All ideological spectrums are vulnerable’

In an era of inflammatory rhetoric around the media, discussions about potential liability are even more important

Evan Ringel is an assistant professor of media law at Appalachian State University. His research focuses on the application of traditional First Amendment principles to emerging technologies and hot-button social issues.

President Donald Trump has made no secret of his disdain for journalists, joking that they should be shot or raped in prison for withholding the identity of their sources. Kash Patel, Trump’s nominee for FBI director, said in a 2023 podcast that he would “come after” the media for their alleged cooperation in “rigging” the 2020 presidential election. A 2024 Gallup poll found that less than a third of Americans trusted the media to report news “fully, accurately and fairly.”

“Everyone who engages in the practice of journalism right now risks jail, litigation, physical harassment and intimidation,” said Chip Stewart, a journalism professor and assistant provost for research compliance at Texas Christian University. “It’s the sort of thing you would expect in foreign countries and tinpot dictatorships.”

While journalists and attorneys have expressed concern about the potential legal risks media members face in a second Trump term, the impact of a new administration remains unclear. Journalists should take actions, such as developing encryption routines and making sure they know their local and state liability laws.

”Everyone who engages in the practice of journalism right now risks jail, litigation, physical harassment and intimidation. It’s the sort of thing you would expect in foreign countries and tinpot dictatorships.“

Chip Stewart, a journalism professor and assistant provost for research compliance at Texas Christian University

“The reality is that journalists across all ideological spectrums are vulnerable,” said Frank LoMonte, senior legal counsel at CNN. “The First Amendment and press freedom are not partisan or ideological issues.” Stewart emphasized that journalists risk legal consequences regardless of who resides in the White House.“ “Some administrations may say the right things about journalists, but they’ll continue to target leakers,” he said.

Still, the Trump administration’s rhetoric and proclivity for litigation against the press signals a serious threat to journalism.

In December, ABC donated $15 million to the Trump presidential library as part of a settlement in a defamation lawsuit against anchor George Stephanopoulos. The willingness of major journalism organizations to appease the new administration may create an untenable situation for smaller newspapers and media outlets.

“We have seen major news organizations who are actively concerned about maintaining a friendly relationship with the new administration,” said Amy Kristin Sanders, the John and Ann Curley Professor of First Amendment Studies at Pennsylvania State University. “What happens at the largest journalism organizations trickles down. If the New York Times and the Washington Post don’t have the support from their bosses and editors to tackle a new administration, how do we expect local journalists to do so?”

“The reality is that journalists across all ideological spectrums are vulnerable. The First Amendment and press freedom are not partisan or ideological issues.”

Frank LoMonte, senior legal counsel at CNN

State and local governments have also played a key part in creating a legally uncertain environment. At least 48 journalists were arrested in the United States in 2024 while covering protests or other news events, while an uptick in state laws limiting abortion after the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization may lead to additional press freedom challenges.

Despite the First Amendment’s sweeping proclamation that there shall be “no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press,” news media members remain at risk for potential legal liability. Sanders pointed to the potential weaponization of defamation lawsuits as a concern for journalists, especially in states that lack anti-SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) laws allowing defendants to seek an early dismissal in lawsuits designed to quash speech.

Similarly, Stewart framed the ABC settlement as a continuing willingness to use lawsuits to chill reporting on the Trump administration, suggesting that settlements may end a lawsuit but simultaneously incentivize further litigation and limit aggressive investigative reporting.

Journalists have also faced legal punishment while attempting to protect the identity of confidential sources. In Branzburg v. Hayes (1972), a divided Supreme Court held that journalists lacked a First Amendment privilege to avoid a government subpoena and refuse to testify in front of a grand jury. The judicial legacy of Branzburg is uncertain. One prevailing interpretation combines a concurring opinion in the case with four dissenting justices to suggest that the First Amendment may provide a limited privilege for reporters refusing to comply with subpoenas for information. However, courts continue to disagree on whether the First Amendment provides meaningful protection for reporters seeking to protect their sources.

“Courts have shown a complete willingness to ignore precedent. That includes in areas that we’ve taken for granted as secure press freedom victories like newsroom searches and open records laws. We have to be hypervigilant everywhere.”

Amy Kristin Sanders, the John and Ann Curley Professor of First Amendment Studies at Pennsylvania State University

At the federal level, the PRESS Act, a federal reporter’s privilege law, passed the House of Representatives before dying in the Senate after Trump told Republicans that they “must kill” the bill. Accordingly, journalists in federal court continue to lack a statutory reporter’s privilege protection.

State legislatures and courts have stepped in to fill the gap, and 48 states either have a reporter’s privilege statute or courts that recognize a limited constitutional reporter’s privilege (Wyoming and Hawaii are the exceptions). Stewart warned that current state-level laws should be watched closely, noting that legislatures may try to curb existing anti-SLAPP or reporter’s privilege protections for media defendants. Sanders noted that prior judicial decisions protecting press freedom are also at risk.

“Courts have shown a complete willingness to ignore precedent,” Sanders said. “That includes in areas that we’ve taken for granted as secure press freedom victories like newsroom searches and open records laws. We have to be hypervigilant everywhere.”

Advice to limit your liability

So what should reporters do to limit their potential legal liability, especially if they’re reporting on hot-button issues? Stewart suggested that they start by limiting their reliance on the judicial system to provide protection.

“The courts and the law are there to protect you — but for a price,” he said. “Courts should not be where journalists start thinking they are going to be saved.”

Another way to potentially limit exposure is to know the laws that could result in a legal challenge. Sanders argued that journalists had a responsibility to make themselves aware of the relevant laws of their jurisdiction.

“How you respond if drawn into a legal situation should be directly guided by the law in the primary location that you’re reporting from,” she said.

“It is a very difficult thing to do, but journalists should adhere to the principle of ‘leave no trail, leave no trace’ in their newsgathering practices. Government agents already cover their tracks and destroy their records. If they’re going to do it, journalists should as well.”

Chip Stewart, a journalism professor and assistant provost for research compliance at Texas Christian University

The most important thing journalists can do is engage in meticulous information security practices. The increasingly online nature of interpersonal communication means that most journalists have electronic contact with confidential sources. Stewart pointed to a lack of government transparency as justification for strong protection of sources.

“It is a very difficult thing to do, but journalists should adhere to the principle of ‘leave no trail, leave no trace’ in their newsgathering practices,” he said. “Government agents already cover their tracks and destroy their records. If they’re going to do it, journalists should as well.”

Similarly, LoMonte said that digital security should be a habit for journalists communicating with sources, especially for those covering hot-button issues like abortion or immigration.

“Digital security is crucial to keeping your sources safe, not just from potential adversaries in the legal process, but also from hackers and malignant third-party actors,” he said. “A reporter using sources in the areas of abortion or immigration who are acknowledging people breaking the law must be extremely careful with information security practices. The stakes have always been high for dealing with people who are acknowledging wrongdoing. The subject matter changes but the information security practices should not.”

“Digital security is crucial to keeping your sources safe, not just from potential adversaries in the legal process, but also from hackers and malignant third-party actors.”

Frank LoMonte, senior legal counsel at CNN

Media organizations should also consider using encrypted messaging and document storage software to protect sources. End-to-end encrypted messaging programs like Signal and Confide can auto-delete messages, while SecureDrop provides an open-source document submission program that allows journalists to securely accept and store documents from anonymous sources.

“If someone is leaking sensitive documents to you and you’re storing the documents on your personal cellphone, there’s risk involved,” LoMonte said. “There is no place that you can have complete confidence. Ideally, you should use storage that you have control over rather than a third party that may not act in your best interest. You should also avoid sensitive conversations over a platform that you don’t have control over.

“Bob Woodward had it right: Meet people in parking garages.”

If a journalist ends up in court, they should locate legal counsel as quickly as possible. If their media organization doesn’t have a dedicated attorney, they should reach out to media law nonprofit organizations that may be able to help. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, the Committee to Protect Journalists and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression are among the organizations with dedicated pro bono attorneys litigating First Amendment disputes involving journalists.

An uptick in litigation and rhetoric targeting journalists may paint a murky picture for the future of the profession, but Sanders noted that legal uncertainty provided an opportunity for collaboration.

“Especially with local news, we have to learn to band back together,” she said. “The us against them of 2025 is us (the press) against them (the government).”

Cite this article

Ringel, Evan (2025, Jan. 29). In 2025, journalists must negotiate a climate of legal uncertainty: ‘All ideological spectrums are vulnerable’. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/in-2025-journalists-must-negotiate-a-climate-of-legal-uncertainty-all-ideological-spectrums-are-vulnerable/