Photo: DepositPhotos

Journalism by postal mail

How to work with writers who don’t have internet access and other structural challenges

Journalism today requires reporters to respond, report and file stories quickly. The assumption is that they have access to cell phones, computers, email, and the internet to do their work. But incarcerated people have none of that.

So how do we work with them?

Our primary method is through postal mail. In the digital age, some people might consider the U.S. Postal Service on its way to obsolescence, but it is an essential mode of communication for anyone working with incarcerated individuals.

The bulk of writers who submit stories to the Prison Journalism Project send them to us handwritten via post. A fraction, who are able to afford typewriters, will submit typed work, but either way, publications must transcribe them before they can edit them, which takes time.

This also means that publications must have a designated postal address to receive the stories. Pre-pandemic, this might have been less of an issue because most organizations had offices. But now, editing teams tend to be dispersed throughout the country, and almost everyone is still spending substantial time working from home. Because writers are not easily reachable, the address cannot change with each assignment. There are safety considerations too — we wouldn’t recommend designating a home address to receive submissions.

Stories must also be sent to a location that is prepared to receive them and can forward them to the appropriate editor regardless of where they are.

The Prison Journalism Project primarily uses Virtual Post Mail, an online mail scanning service that has an address in Delaware which we provide to our writers. A volunteer downloads the scanned mail once a week and drops them into a folder that an editor sifts through to prioritize submissions. It’s not a perfect solution because submissions can get lost, and the service shreds the original mail after two weeks. But it’s the best solution we have found so far.

The biggest challenge by far is the length of time it takes to send and receive mail.

“Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds,” goes the saying that acknowledges the dependability of U.S. postal workers.

That may still be largely true of the postal service, but it doesn’t take prison mailrooms and mail policies into consideration.

The vast majority of incarcerated people in this country are held in state prisons that are each governed by separate departments of corrections. That means that each state has a different mail policy that governs what people inside can receive and send out.

In Arkansas, there is a limit of three pages in a single envelope. In Kansas the limit is an ounce, while in California, it’s 13 ounces. In Pennsylvania, prisoners only receive copies of their mail. If you were to send in a double-sided page, they would only receive one side. Many prisons ban Post-its and stickers — a formerly incarcerated friend explained to me that it was because prison administrations suspect that drugs could be smuggled into the adhesive.

There are other rules that are not always written down about how envelopes must be addressed, and what information the sender must include. These rules are separate from the rules and censorship that incarcerated people are governed by in their outgoing mail. A violation of any of the above and more means that mail could be rejected in either direction.

For the past five months, I’ve been trying to connect with a prison journalist in a South Carolina prison. I sent him letters three times only to have them returned because the prison found some fault with them.

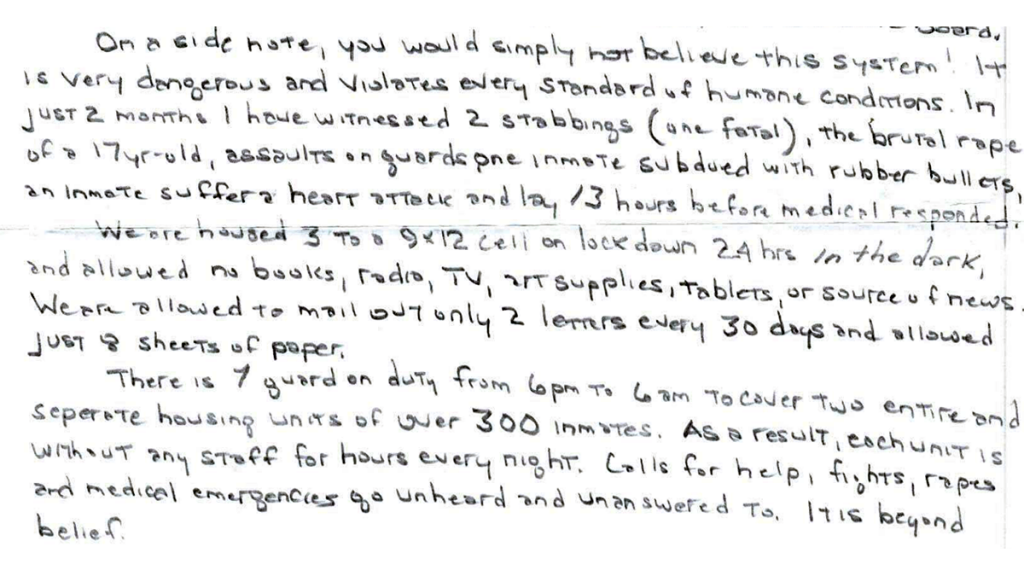

When I finally received a letter from him, it said that he had written to me several times. “We are allowed to mail out only two letters every 30 days and allowed just 8 sheets of paper,” he wrote, adding that the cell has no lights, and they are allowed no books or sources of news.

We have another writer whose work has incensed the staff at his prison so much that they have slowed his mail to a crawl. He has yet to receive a certified envelope we sent him two months ago, even though online records show that the prison accepted it less than a week after it was sent.

A secondary method of communication that we increasingly prefer is via prison email systems such as JPay or Corrlinks with writers in prisons that allow access to tablet-like devices. However, their use requires registering with each of these services separately, and depositing money to pay for electronic stamps to pay for each message. For media organizations that do not regularly correspond with incarcerated individuals, this might feel like a big hurdle.

Even then, however, messages are rarely sent and received instantaneously because prison systems have differing monitoring policies. On top of that, some prisons only allow people outside to send in Jpay mail, which is then printed and distributed. Prisoners do not have the ability to send electronic messages back.

We’ve learned the hard way to be careful about how to word correspondences with writers in certain states. In some prisons, mentioning words like “warden” are automatically flagged for extra scrutiny. In others, sending in a W9 form could be problematic.

Occasionally we are asked by newsroom partners about whether they could communicate with our writers via telephone, which can also be a challenge. Not only do you have to create an account with the designated phone provider, most states require the prisoner to register the names of those who they can call; many of them put a limit on the number of names each person can list. Even if a writer put an editor’s name on a list, approval could take days. Finally, prisoners cannot receive inbound calls, and it’s difficult to schedule calls because phones are subject to availability during a limited window of time.

Here are a few lessons that will help newsrooms start their work with incarcerated writers directly:

1. Build in as much extra time as possible for the project and then double it

When we send out mail, we usually factor in 3-4 weeks to get the first response. Even a JPay email could take 24 hours at minimum. In Illinois, it could take three days before a prison greenlights an inbound electronic message.

2. Have a backup plan

Even if you plan well and are lucky enough to experience smooth communications, there is always the chance of sudden lockdowns, transfers to another prison, and isolated quarantines — especially in pandemic times. This means that, for important stories, you should always have a contingency plan.

3. Address envelopes clearly and follow the rules

Every prison or state department of corrections has a section on its site that provides mail rules and address format. Note that the address for the prison and the address for “inmate mail” are sometimes different. In Pennsylvania, for instance, mail is handled through a service in Florida.

4. Schedule a window of time for phone calls and have a contingency agreement

People in prison typically have designated windows of time that they can use the telephone, but they cannot schedule calls precisely because their ability to call depends on the availability of the phones. I usually schedule a half-hour window. If I don’t pick up, I ask them to try me again immediately and try me a third time approximately an hour later.

5. Make sure you are crystal clear in your intentions, questions, requests and edits

You can minimize the number of times you must communicate with the writer. Even in the best of situations, each exchange will add to the time it takes to complete the project.

Given all of the challenges, hurdles and restrictions, it’s tempting to give up and move on — but these are also the reasons why incarcerated voices have had such a hard time being heard. It makes it all the more important to publish their perspectives, experiences and reported stories.

Comments