Matia Wright’s TikTok

What newsrooms can learn from creator culture and monetization strategies

Like the music and movie industry before us, it’s time for journalism to rethink the way things are done

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Reynolds Journalism Institute or the University of Missouri.

Matia Wright is an 18-year-old student who wanted to major in journalism at Georgia State University. She grew up in a small, conservative town and was excited to be living in Atlanta, the home of CNN headquarters. “My mom was concerned about me getting a job, but I was thinking about broadcast journalism because I really like writing,” Wright recalls. “But I woke up one day and decided that I don’t want to be watching history, I want to be making history.”

In May 2020, Wright began posting videos on TikTok, and in February this year she created a TikTok explaining why she changed her major from journalism to law. She had watched videos of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, and realized that “the best way to seek undeniable and recognizable #change is through #legislation,” as she wrote above her TikTok video. She beams with confidence as she shares with more than 343,000 viewers that her ambition is to go to law school and eventually run for Congress, but for now, she describes herself on LinkedIn as “Political Science | Sociology | Social Media Entrepreneur.”

Wright, of course, is one of millions of people participating in the ever-growing creator economy. In a 2019 study conducted by Morning Consult, “no less than 86% of people ages 13 to 38 are willing to try out influencing.” About 58% of survey participants who identified as Gen Z (respondents between the ages of 6 and 24 years old) said their number one reason for becoming an influencer was to “make a difference.”

The popular notion that social media creators are primarily chasing fame is an antiquated and oversimplified claim. It deludes professionals, like journalists, into believing that creators, like Matia, shouldn’t be taken seriously. From the surface, creators are just offering commentary, making memes, or dancing on-camera (which many are!), but the real action is happening within their comment sections (a feature most news organizations have removed from their websites) and their private messages.

Popular creators are essentially community organizers, building a relationship with their viewers in increasingly intimate ways. Acts of vulnerability on-camera may still be performative, but whether creators are sharing their childhood stories or live streaming their day-to-day lives, the consensus is clear: People crave that sense of connection and want more.

Ev Williams, the CEO of Medium, calls this phenomenon relational media. In a recent post announcing significant editorial buyouts, he accurately describes “how credibility and affinity are primarily built by people — individual voices — rather than brands.” This trend might seem inevitable for people who grew up loving bloggers, but for legacy newsrooms and new publications, Medium’s pivot is a harbinger of things to come.

Jarrod Dicker, who actively writes about the creator economy while being the VP of Commercial at the Washington Post, is an optimist. Yes, media companies are brand-led, but he believes they could be “the premiere supportive operation when creators want to build their own brand.” “The one big critique for the creator economy is that it only takes into account bylines,” explains Dicker. “It doesn’t assume the need for editors, audience development, developers, or biz dev people.” It’s true. The opportunity for media companies to bet on creators, restructure their operations, and act more like a talent agency or record label is ripe for the taking, but it’s antithetical to how news organizations have traditionally thought, operated, and made money.

It’s why even the exploration of new monetization strategies, like micropayments, within journalism are still framed by the presumption that people prefer inscrutable brands rather than a personal relationship with creators.

“But there is a simple solution,” proposes Mark Stenberg, an AdWeek reporter covering the creator economy. “Why not, for say $15, give the digital reader access to unlimited articles on the website for a week, maybe even a month?” he writes in his personal newsletter. “Call it a monthly access payment (MAP),” Stenberg proposes, rather than what it is: an alternative way to subscribe to a publication. Stenberg’s good intentions reveal his bias for publishers and obscures the paradigm shift happening before our eyes.

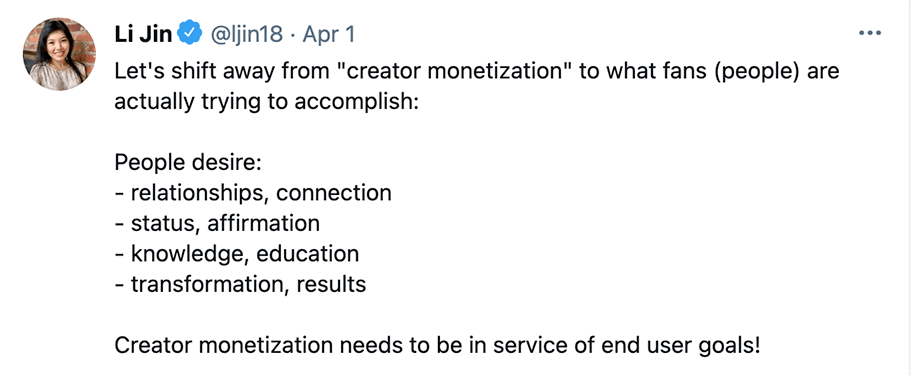

Li Jin, an investor who pioneered “The Passion Economy and The Future of Work,” has relentlessly championed creators and the people who support them. She recently tweeted:

Jin is making a subtle, but critical distinction: in the creator economy, people aren’t paying for content, they’re backing a creator they believe in. Fans aren’t looking to collect newsroom branded tote bags, they’re looking to feel recognized and affirmed by the storytellers they follow. Monetization strategies should be designed for viewers, readers, and listeners, first and foremost.

It’s no coincidence that YouTube, Twitch, Tiktok, Twitter, Clubhouse, and Soundcloud are all evaluating or building tipping features onto their platforms. The idea of virtual tipping isn’t new, but their cultural adoption conveniently coincides with the rise of creators. People have already been adding their Venmo or PayPal account to their TikTok or Instagram bios, but when tipping is formally implemented, like on Twitch, independent streamers have been able to cash out big. Similar to subscribing to your favorite writer’s Substack, people may not read every newsletter, but they want to show their support for the individuals they’ve come to trust and respect. Like the real-world service industry, tipping is a form of expression online. It’s not a philanthropic donation or a transactional subscription to a newsroom, it’s a way for consumers to say “I love what you’re doing,” and when the life of a creator gets hard, which it often does, it becomes “I’m here for you. Please don’t give up.”

Relational media is here to stay, but it’s an open question as to how news organizations will adapt. The lesson to internalize from Matia and millions of people like her is that people don’t need to study or get a job in journalism to get a taste of its power. The ability to impact and inform the masses is available to anyone through an app, and it’s no wonder that the majority of news publications, large or small, are struggling to survive.

The irony is that as platform companies design more features for creator growth and monetization, individuals like Matia still rely on mainstream news coverage to educate herself as well as her audience. But whether it’s possessing a brutally honest demeanor or leveraging TikTok’s AI algorithm, creators are outperforming news companies when it comes to relating with everyday people, cultivating a community, and amplifying their own work.

Like the music and movie industry before us, it’s time for journalism to rethink the way things are done. In the years to come, the wave of digital creators is only going to grow, but instead of fighting it or minimizing its constituents, news organizations should partner with creators and design products that genuinely connect with the people we were always meant to serve.

Author’s note: This is the second column in a two-part series about the creator economy. Read Yvonne’s previous column here.

Comments