Independent filmmaker Resita Cox and producer Alexis Bell begin production on the documentary Basketball Heaven on Jan. 11, 2024, in Kinston, N.C. Photo: Donnie Seals Jr.

Why diversity in freelance photojournalists matters

Building a visuals toolkit for newsrooms without visual staff that will provide resources on how to work with photojournalist freelancers with an emphasis on equity and diversity

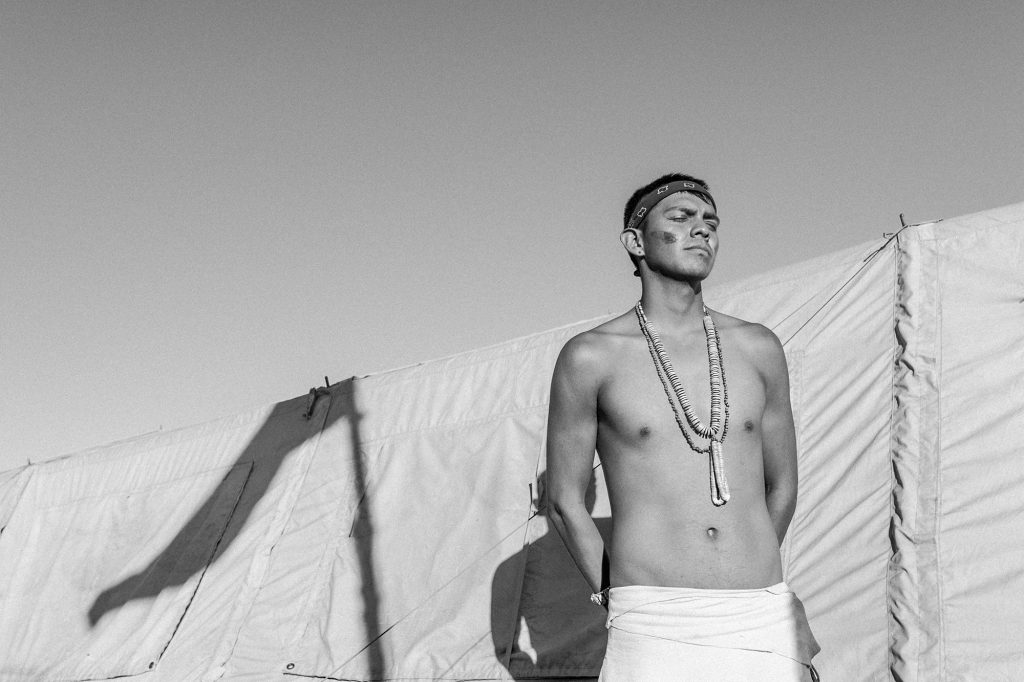

Photojournalism can be a tool to see all the varied stories of the world or one that reinforces the status quo of a homogenous society. That’s why the diversity of people behind the camera matters: who they are impacts which stories are being told and how.

For our RJI Fellowship, we will be building a visuals toolkit for newsrooms without visual staff that will provide resources on how to work with photojournalist freelancers with an emphasis on equity and diversity to increase engagement and revenue.

In this article, we’ll outline how to find diverse photographers as well as how to build your own database and set goals to prioritize diversity.

Why it matters

Diversity of visual journalists leads to increased access to a wider range of communities and perspectives. Marginalized communities are more likely to be included and documented with nuance. That informs how we perceive our world and our collective memory of it. Without diverse representation our understanding of our communities and our history is biased.

In an industry historically dominated by white and male perspectives, we still see a significant lack of diversity today. Of the 1,018 photographers who took part in the 2018 World Press Photo State of News Photography survey, more than 80% were men, 52% identified as White/Caucasian and only 1% classified themselves as Black.

“I see diversity in photojournalism and journalism [at large] on a sine curve,” said Kyndell Harkness, who worked as a photojournalist and photo editor for 20 years and is currently Head of Culture and Community at the Star Tribune in Minneapolis. She has also worked as the Assistant Managing Editor of Diversity/Community.

“In the nineties, we were doing great,” Harkness said. News organizations made strides toward diversity. There were efforts being done to beef up those ranks that were new and different. After the nineties when newsrooms were in decline and we got budget cuts, that diversity went away.”

Harkness noted that after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, local, national and international outlets leaned on Black freelance photographers for access to Black communities whose trust the outlets had not yet earned. These freelancers offered more nuanced and authentic coverage, but this didn’t always lead to continued support or assignments when the news cycle moved on.

“The deep knowledge those photojournalists have of their community is priceless,” Harkness said, adding, “I am curious to see, now that the rawness of those protests is waning, which news organizations are actually developing the pipeline that is sustainable, regardless of budget constraints.”

Josué Rivas has observed Indigenous and Black photographers leave the industry after feeling tokenized by news outlets. Rivas co-founded INDIGEVSION, formerly known as Indigenous Photograph, a database of more than 100 Indigenous photographers across four global regions, in 2017. About 90% of the database’s requests are for Indigenous People’s Day or Native American Heritage Month, but editors don’t often call these same photographers for other assignments, Rivas said, adding that the process of addressing that needs to be proactive rather than reactive.

“We are trying to untie a knot that has been part of the makeup of this country,” Rivas said. “We used to have slaves and we used to kill Indigenous people for their land. That’s the real knot of diversity and inclusion.” He wants people to acknowledge that it takes going beyond performative allyship and diversity and instituting structural change to confront a knot of that nature. There needs to be a collective effort to shift the power dynamic.

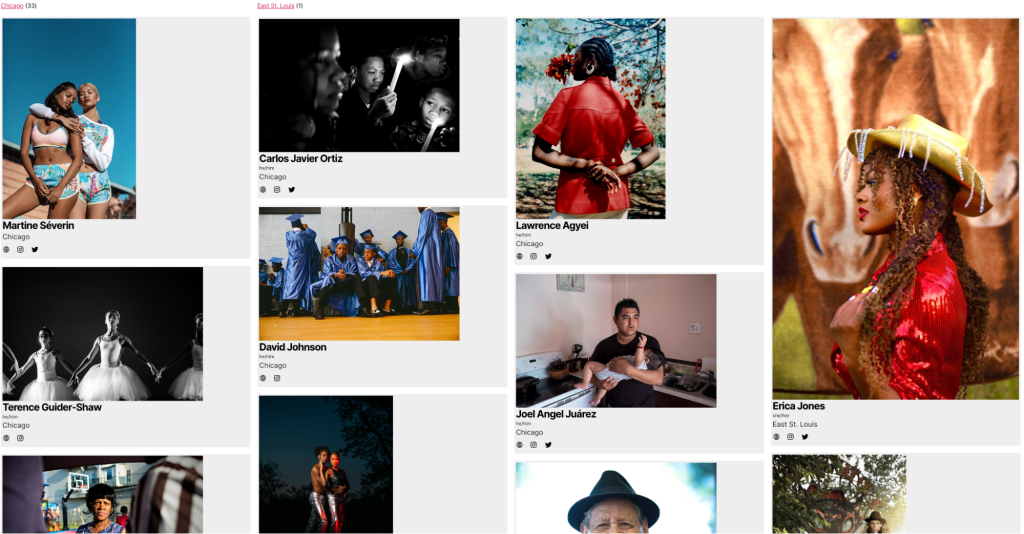

Databases to help increase diversity

Our approach to finding a photographer emphasizes diversity so that photojournalists are as diverse as the communities they document. For the purposes of this article, we are focusing on the U.S. Several affinity database groups offer their private databases at no extra cost. You just need to register. These databases allow searches by skill set and offer additional contact information. Be sure to budget at least ten days to get access to the private database.

Diversify Photo’s database features 1,330 vetted photographers by state and city. You can also search their UpNext list of emerging photographers. Request access to the private database which has additional information on the photographers. The database includes international members.

Women Photograph features 1,449 photographers in its database. Search by region, expertise, skills and certifications, gender/sex identity and race/ethnicity. You can request access to the private database, which has additional information on the photographers. The database includes international members.

Black Women Photographers only offers a private database. It’s free but requires 7-10 business days to gain access.

INDIGEVSION, formerly known as Indigenous Photograph features almost one hundred photographers organized by region. Request access to the private database, which has additional information on the photographers including geographical, areas of expertise, languages spoken and contact information. The database includes international members.

SWANA Photograph features “image makers with roots from the SWANA region working worldwide in editorial & commercial.” You can search by region. There are currently fourteen listed in the “Turtle Island / U.S. & Canada” section.

Color Positive features a list of 80 Black photographers organized alphabetically by first name.

Everyday Projects organizes Everyday Project contributing photographers by region. This started with Everyday Africa “as an effort to present a more accurate depiction of life on the continent and to direct a critical eye toward the international media industry in which they worked.” and “has been a force for correcting journalism’s unbalanced history.” It has since evolved to include projects such as @EverydayBlackAmerica, @EverydayAmericanMuslim and @EverydayRuralAmerica.

The Authority Collective is currently working on building a new member database.

If you know of additional databases we should include, would like to provide feedback, collaborate or raise specific questions or topics that you would like to be included, please email info@prismphotoworkshop.org. And you can subscribe to the Prism Photo Workshop newsletter to stay up to date on our work.

How to make your own diverse database with photographers who are local to you

Below are some basic questions that will assist you in building your own local database and inform who to commission for a particular assignment.

- Contact info: Name, pronouns, email, phone number, website, social media handles

- Race/ethnicity: African, Arabic Descent, Asian, Black, Indigenous, Jewish, Latina/x/o, Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander, White and Other.

- Gender/Sex Identity: Cisgender Woman, Cisgender Man, Gender Nonconforming, Intersex, Nonbinary, Transgender and Other.

- Location: City, state

- Expertise: i.e photojournalism, documentary, portraiture, underwater, architecture, music, architecture and sports

- Additional Skills: i.e. photo illustration, drone photography, reporting, writing, studio lighting, video, video editing, audio and audio editing

- Valid license and vehicle access?

- Valid press credentials? (If not, share local links or resources for photographers to obtain credentials. This is often important for access and protection to city council meetings and protests)

- Languages spoken:

- Hostile environment training experience?

- Other certifications: i.e. FAA-certified drone photography/license and insurance, SCUBA certification

- Other notes: i.e. have they worked with your publication, do they have personal protective equipment access, etc.

You can make a copy of our Freelancer Intake Form that includes the fields above and edit it to meet your needs. We recommend setting the responses to auto-populate a Google Sheets page.

Diversity by the numbers

According to The News Leaders Association (NLA), “diverse newsrooms better cover America’s communities. In 1978, the association challenged the news industry to achieve racial parity by 2000 or sooner and released the results of its first annual newsroom employment census. Over three decades, the annual survey has shown that while there has been progress, the racial diversity of newsrooms does not come close to the fast-growing diversity in the U.S. population as a whole.”

Forty-four percent of Americans identify as Black or African American, American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander or Mixed-race or Latino according to the most recent U.S. Census Bureau data from 2023, In contrast, people of color comprised only 21.9% of salaried employees reported by all newsrooms, according to the most recent ASNE survey. Overall, people of color make up only 18.8% of newsroom managers at both print/digital and online-only publications.

According to Tara Pixley, former RJI Fellow and co-author of Catchlight’s State of Photography 2022 Report, of special concern are the gaps in pay and access to resources along racial and gender breakdowns. “People from historically marginalized communities — Black, Indigenous, nonbinary, women, etc. — are making far less money, are less likely to have access to health insurance and are winning fewer professional accolades,” Pixley said, “That is shameful, and we have to address it as an industry.”

It is clear that, almost 25 years later, the journalism industry is still nowhere near the NLA benchmark of racial parity by 2000.

Newspapers increasingly rely on freelancers rather than staff photojournalists, which further limits the diversity of voices and who can afford to remain in the industry. In a recent survey of 48 freelancers published by A Photo Editor, data showed that “despite newsroom pronouncements about equity, diversity and inclusion, photographers from traditionally underrepresented communities – including women, people of color and people from low-income backgrounds – often cannot afford to work in photojournalism long term. Those who can survive the abysmal rates often come from wealth or have another form of financial support, like a spouse with a well-paying job and benefits.”

“We’re seeing people leave the field; people who have really critical work experience and job skills that allow them to do assignments better,” Diversify Photo co-founder Andrea Wise said. Established in 2017, the organization’s database of vetted photographers facilitates editors commissioning visual storytellers from underrepresented groups.

“A lot of those photojournalists have families or other life responsibilities or just realizing that they need a retirement plan. The marketplace is shifting where there are a lot more folks coming into the field going directly to freelance without experience from internships or staff jobs that used to be more common. And so, as an industry, we are increasingly more reliant on people who are less and less experienced,” she said. Another consequence of this is that the training, mentoring and education of these photojournalists often fall to small volunteer and POC-run groups like Diversify Photo, Wise said, rather than traditional employers.

How to move forward to further diversity

Analyze the current diversity in your freelancer pool and among editors working with freelancers or making decisions about their content. Track your work and set goals to reflect the demographics of the communities you cover. Check in quarterly and annually to follow up on progress and any challenges you may encounter.

Investment has to happen in freelancers too. Take the initiative to recruit emerging photographers from diverse backgrounds, develop relationships with them and offer access to training and resources. Give them feedback and help them apply for awards.

Rivas recommends asking freelancers for feedback in turn and paying them for their time. Making the space for that feedback builds trust and currency. “We all have something to learn,” he said.

Harkness sees a future in which local news organizations work in concert to train people from their communities as a solution to talent and pipeline cultivation.

“This [diversity in visual journalists] is a critical need. If we don’t get that piece right with the people that we have in our organizations right now, as we develop, we lose a key part of how we can quickly get to relevance. And relevance is probably the biggest battle that journalism as a whole has on its hands,” Harkness said.

Harkness encourages outlets to look at this issue of diversity more holistically. She sees newsrooms addressing audience reach and engagement via new products or varied writing voices, but she argues diversity in visual voices is a large part of that answer.

Cite this article

Kanaar, Michelle; and Schukar, Alyssa (2024, Aug. 13). Why diversity in freelance photojournalists matters. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/why-diversity-in-freelance-photojournalists-matters/