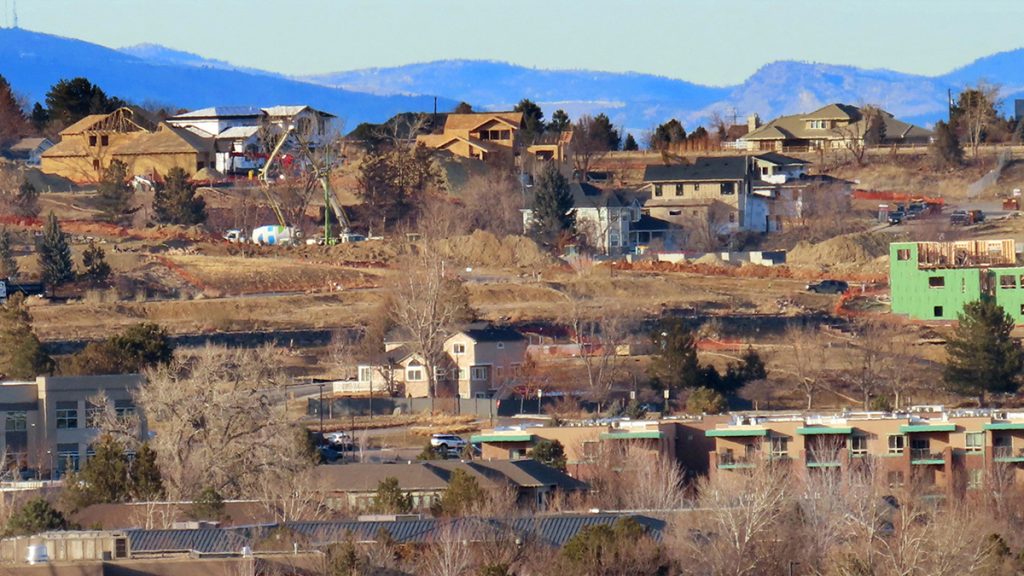

Homes destroyed by the 2021 Marshall Fire can be seen being rebuilt in the burn area near Boulder, Colorado. Photo: Don Kohlbauer | Boulder Reporting Lab

How a pop-up community newsroom shed light on wildfire health impacts in Boulder, Colorado

We’re building a guide to help newsrooms fill voids in deep-dive reporting with their communities

It was April 2021, and the devastating Marshall Fire had recently ravaged more than a thousand homes near our city. I was participating in a journalism panel when the mood turned somber during small talk. Survivors were present, and they began sharing their stories of profound loss. Among them was a woman, still living in the burn area, whose home was spared from flames. Despite this stroke of luck, she was grappling with health problems – a new cough that medication couldn’t suppress, a rash covering her body, occasional night time nosebleeds.

For Boulder Reporting Lab, the nonprofit local newsroom I founded in late 2021, it was clear we needed to cover this story for our community. Our newsroom had been reporting on the impacts of the fire on drinking water, and we knew there could be other health effects as well.

Wildland-urban interface fires are particularly horrific, not only consuming trees and vegetation but also homes, cars and various human-made materials. The toxic particulates from these materials contaminate the water, soil and air. They also lurk in the walls of still-standing homes, I would later learn.

At the time, BRL was three people, working hard to build a sustainable newsroom from scratch. Investigating a story of this magnitude demanded more reporting bandwidth than we had available. Realizing the scope, I reached out to my journalism colleagues at the Center for Environmental Journalism at CU Boulder. Collaborating seemed like the best approach. They agreed, and within a week, a plan was hatched.

Hillary Rosner, the center’s acting director and a journalism instructor, proposed turning our collaboration into a course involving graduate students from both journalism and sciences. Our vision was to delve deeply into the story for one semester, with a team of seven student reporters and two editors, myself and Rosner, working in tandem with our community.

And, Boulder, our first community pop-up newsroom was born.

The roots of pop-up newsrooms

Pop-up newsrooms aren’t new. In Calgary, Canada, The Sprawl made headlines several years ago when it filled a local news void by establishing a temporary pop-up newsroom to cover its city election. The Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism pioneered a version where it set up shop in neighborhoods and generated stories with community members on the spot. Honolulu Civil Beat’s pop-up newsrooms occur in public libraries across Hawaii and the goal is to bring its journalism and journalism into communities.

Our project felt different, personal. It seemed to emerge spontaneously from our community, driven by an unstoppable force to meet a pressing information need. While its scope was intensely local, the void it filled resonated on a national level.

Boulder, like many other markets across the country, has seen the deterioration of its century-old-plus newspaper, especially a lack of investigative reporting. The outcomes of our initial pop-up newsroom far exceeded our expectations. We established publishing partnerships with The Conversation and KUNC public radio. The students, from various disciplines, gelled as an investigative news team, and their focus remained firmly on serving the community. Their efforts were recognized when they won the Public Service award at the SPJ regional journalism awards, and we were also named finalists for the INN innovator award and LION’s Collaboration of the Year award, among others.

Most importantly, the work provided crucial and timely information for our community and beyond, shedding light on a little-known impact of wildland fires that has devastated local families. Other newsrooms in the state began to cover stories about “standing home” survivors — a term coined by our pop-up newsroom. The response was overwhelming, with emails pouring in, thanking us for addressing urgent information needs.

Replicating our efforts

As fellow RJI fellow Ariel Zych described it when we all met last month, BRL is spearheading a “locally focused capacity surge” — or a “capacity sprint” — to deeply inform communities when it feels impossible to do so due to smaller staff sizes. And it can be done anywhere.

If your community is anything like mine, the vast expertise and subject matter knowledge among residents is astonishing. These individuals often serve as sources in our stories but we can do more with their knowledge and enthusiasm beyond just quoting them in articles.

While not everyone may want to make journalism, there are those who do, and others who are driven by the desire to make a difference for their neighbors, much like all of us who choose to work in local news. In our first project, we worked with local scientists who contributed to an accompanying story, enhancing the authority and credibility of the journalism.

We can expand the definition of what it means to be a journalist. For instance, when your town faces a flood, you could create a pop-up community newsroom to cover the insurance issues together. Or, if local retirees are feeling neglected in the affordable housing conversation, let’s investigate the matter collaboratively. What about young people covering the local youth mental health crisis and lack of services? We could establish a micro newsroom where we teach reporting skills, and in return, the community helps us tell better stories that otherwise might not be told. The potential for collective action and impact is inspiring.

But how can small newsrooms even take on such an initiative, given our limited resources? We don’t have all the answers yet but BRL is currently in the second iteration of our community pop-up newsroom experiment and learning as we go.

These insights will ultimately serve as the foundation for my RJI fellowship project, a guide to assist small local newsrooms in creating their own “capacity surge” through pop-up community newsrooms. It also seeks to open a conversation about local investigative journalism innovation and potentially steer this idea toward us working with our communities, not just for them, towards a more promising future.