A workshop on misinformation in a Vietnamese community center in Boston. Photo: Saoli Nguyen

How we created community-driven investigations for immigrant audiences

Using a needs assessment and theory of change to inform and empower the Vietnamese community in the U.S. about misinformation

“Do any of you know what AI is?” I asked a group of 30 Vietnamese immigrants in Oakland during a workshop on misinformation in 2024. I was trying to explain to them what deepfakes were and how AI was producing ever more false or misleading information. News coverage of AI and its myriad impacts on everyday life had been rampant for months by then.

Despite all those headlines though, no one raised their hands. These elders had never heard of AI, they said.

I had covered stories from the social web for more than a decade but only in recent years did it occur to me that much of the work I did was in English and for an English-speaking audience. I thought there was widespread knowledge of dis- and misinformation, media manipulation and the polarized information ecosystem we all inhabited. But I realized that false or misleading content was largely able to flourish in non-English realms across the U.S. in part because much of the reporting about the subject was never truly focused on what happened in immigrant communities and because the big tech companies tended to prioritize English speakers when implementing any accountability measures.

I’ve spent the last two years looking into stories around misinformation, scams and tech literacy in the Vietnamese community. To me, it serves as a prism into how misinformation and bad online conduct goes unchecked in niche communities.

In this article, I’m sharing some of the things I’ve learned, including how to:

- start your project with the community

- pick stories that are most relevant to them and deliver information in ways that are most effective

- find metrics of success that center the community

Finding stories with communities

A key aspect of this project was to investigate stories and topics that originated from our communities. Instead of taking a top-down approach to journalism, I wanted to make sure that the stories I ended up reporting originated from testimonies from the community.

The main idea behind this approach, or the theory of change driving it, was the assumption that if we write stories that originate from the community and deliver them on the platforms that they already use, there will be a natural audience for this work that will also be more likely to act on the information they receive.

Therefore, I started this effort by doing an information needs assessment with one community that consisted of Vietnamese immigrants above the age of 50 in Oakland, California. I conducted a focus group interview with 30 people, did individual interviews, and analyzed the YouTube archive of one volunteer who donated her YouTube viewing history (17,000+ videos). I learned that many community members relied heavily on YouTube to receive information about vital aspects of their lives, including health advice, financial tutorials and news from influencers who translated sites like Newsmax and Breitbart into Vietnamese. Many of them were served this information through automated recommendation systems or targeted ads.

Picking what stories to tell and how to distribute them

The insights I gained from these initial interviews helped me find issues to investigate further and topics on which I could produce actionable guides and tipsheets.

Community members told me that they found a lot of the information they received on YouTube to be skewed and of low quality, even if they relied heavily on the platform for their information needs. I decided to do more in-depth stories about political influencers which community members pointed out as problematic but that, unlike their English-speaking counterparts, received little to no attention from news organizations. I also received several tips from Vietnamese immigrants about online medical scams that involved targeted ads featuring popular singers and fake websites.

Beyond writing these stories we also wanted to make sure their content is distributed in various ways. We collaborated with Viet Fact Check, a nonprofit that focuses on bringing media literacy to the Vietnamese community, to translate and distribute our articles online. We also co-published some of our investigations with Viet Bao, a Vietnamese newspaper that costs 25 cents and is distributed across California. I purposefully sought out Vietnamese YouTubers and spoke on their shows about the stories in (broken) Vietnamese because that’s the platform where Vietnamese people already were.

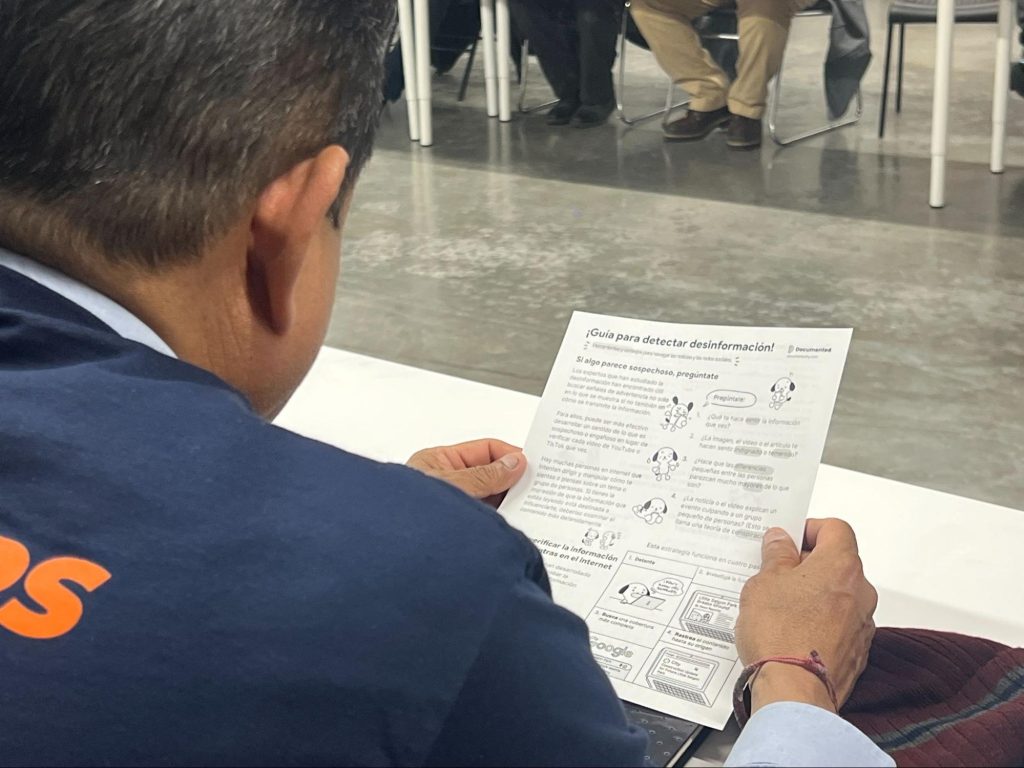

What emerged from the needs assessment, too, was that the Vietnamese community expressed a need for resources that could help them understand and navigate misinformation online. To address this, I wrote stories about spotting misinformation online, which we turned into a tipsheet in Vietnamese and English (and later in other languages, including in Khmer, traditional and simplified Chinese, Bengali, Spanish and Haitian Creole). A Boston-based non-profit gave out 3,900 translated tipsheets on misinformation among Chinese, Bengali, Khmer and Vietnamese community members. And the Brooklyn Public Library distributed 3,000 tip sheets on misinformation in English, Spanish, Haitian Creole, Chinese and Vietnamese across their libraries.

Our Vietnamese interviewees also seemed to enjoy learning about issues in person. Thus I started providing hourlong workshops. This material and the problems identified through the investigations became the basis for this workshop series. To ensure we would reach a lot of people, we partnered with established Vietnamese community organizations across the country, including the one that initially connected us to the elders in Oakland.

Last but not least, I did a story about a retired grandmother, Mai Bui, who started fighting misinformation in her community by translating mainstream news into Vietnamese, one Youtube video at a time. This story was a way to show what other community members were already doing. A big part of what the Vietnamese focus group members expressed was a desire for agency and self-empowerment when navigating the internet and the grandmother-turned-influencer modeled just that to her peers.

What was striking was that a lot of the components of this project are not the kind of pieces that I would associate with a typical investigative project. One of my colleagues thought that these bundles of stories are more akin to ‘investigative campaigns,’ an approach of bringing vital information to immigrant communities that included digital and in-person experiences as well as narrative and practical formats that all complement each other.

Measuring success

One of my favorite frameworks for measuring impact was developed by Reveal that classified impact on four levels:

- Micro: individual

- Meso: group

- Macro: government, institutions

- Media: other outlets

On a macro level, we were able to bring attention about medical scams in the Vietnamese community to YouTube. Administrators shut down multiple channels associated with medical scams that we brought to their attention with our story.

On a meso or group level, our story about the grandmother and YouTuber Bui spread throughout the Vietnamese community throughout. Employees of the nonprofit Stop AAPI Hate read our story about Bui and featured her and her work in a San Francisco-wide poster campaign during AAPI month. Another Vietnamese language newspaper picked up her story as well.

But since our theory of change was largely focused on empowering immigrants, the most important measure was whether this work was actually reaching Vietnamese immigrants, something that is a micro-level impact measure.

One of the most successful ways to reach Vietnamese people with our reporting was to appear on YouTube shows of Vietnamese influencers. Accumulatively, our content received more than 59,000 views of Vietnamese speakers across multiple videos.

But the workshops were incredibly important, too. We held or helped set up more than 55 workshops on misinformation in the U.S., primarily with the Vietnamese community but also with the Chinese, Korean and Spanish speaking communities. For each workshop we hosted between 10 and 60 people. About half a dozen workshops were with community organizers, ethnic media journalists and other direct-service providers who wanted to learn about how they could better assist their own communities on the subject of misinformation.

We would love to hear from your efforts to experiment with journalism-based change-making. Feel free to fill out this survey to stay in touch or to book some time with Nicole.

Cite this article

Vo, Lam; and Lewis, Nicole (2025, Dec. 3). How we created community-driven investigations for immigrant audiences. Reynolds Journalism Institute. Retrieved from: https://rjionline.org/news/how-we-created-community-driven-investigations-for-immigrant-audiences/