Newsrooms come together to tackle problem of digital news preservation

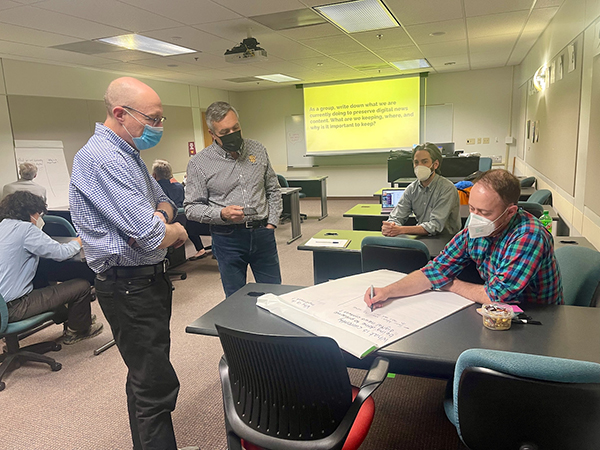

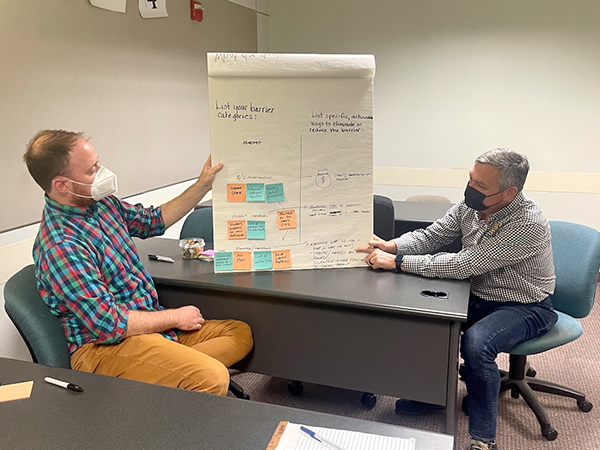

Leadership from each of the Missouri School of Journalism’s professional media outlets gathered together in a conference room in late April, no small feat for a group in charge of “feeding the beast” of news media day after day while also juggling teaching responsibilities at the School. The challenge that brought them together? Preservation and accessibility of digital news archives.

Even today, it can be jarring to think of digital media as having preservation issues. Digital media was once the answer to news preservation, a seemingly limitless, instant archive for stories that would otherwise fade and rot on newsprint. But the widely understood realities of larger file sizes, limited server space, and aging hardware infrastructure have collided with shrinking newsroom budgets and myriad other pressing priorities, largely confining the issue to the back burner despite its worrisome implications for the future.

Now, at the School of Journalism’s Reynolds Journalism Institute (RJI), a group of news veterans are addressing the problem with a sense of urgency, though the path forward remains murky.

“The technology exists to solve this problem, but unless you’re the New York Times or the Washington Post, you can’t afford it,” said Edward McCain, director of the Journalism Digital News Archive, a digital news access and preservation initiative. “What you can do is come up with a policy that governs how you archive stories and assets under the financial and technical constraints of a modern newsroom.”

In the April gathering, leaders from daily newspaper the Columbia Missourian, NBC TV affiliate KOMU, NPR member station KBIA, Vox Magazine and the digital-only Missouri Business Alert started by working together to understand the individual challenges each newsroom was facing. Some were surprised to learn that back in 2002, the Missourian lost 15 years’ worth of stories and photographs to a server crash. A few years later, the process of migrating to a new content management system resulted not in a total loss, per se, but in the erasure of important metadata that made re-cataloguing and re-formatting archived stories a grueling, time-consuming process.

It quickly became apparent to the group that content management systems (CMS) were the source of many aches and pains surrounding digital content preservation. Though any one system might have a perfectly serviceable approach to content storage, the reality is that news organizations change systems relatively frequently as needs and costs change, and — as the Missourian found out firsthand — there is no guarantee that digital archives will survive the transition.

It quickly became apparent to the group that content management systems (CMS) were the source of many aches and pains surrounding digital content preservation.

But CMS issues are only part of the problem. Average file sizes for even the simplest file types are now many magnitudes larger than in 2000, and video files in particular have ballooned in size as resolution increased and sound quality improved, making complete archiving a near-impossibility for TV stations that must constantly make room for new, high-resolution content.

“We don’t have the greatest system right now,” said Jeimmie Nevalga, KOMU-TV’s news director. “If we know a story’s important, we manually save some of the video that has aired. Our catch-all is that we share most of our stories online—at the very least, we have that saved. But if we aren’t careful, we will lose content.”

Nevalga hopes the development of a preservation policy will eliminate some of the risks of this laissez-faire approach, but the fact remains that using an online platform as a makeshift archive is at best a temporary band-aid, especially when storing voluminous video files. Yet, as an easy fix that doesn’t require additional personnel, time, and money, it’s a solution that’s far more common than the New York Times’ meticulously curated and searchable digital archives.

“What we’re doing isn’t really archiving,” acknowledged Elizabeth Stephens, executive editor of the Columbia Missourian. “A lot of what we’re doing in terms of organizing stories and making them searchable goes away if we change our CMS. An archive is a more permanent solution, and we just don’t have that.”

Indeed, while TV stations like KOMU are facing the heaviest pressure of ever-increasing file sizes, the problem of organizing stories and assets through consistent use of metadata and other storage guidelines is one that each newsroom’s leadership sees as an urgent hurdle to overcome. Posting every story online, after all, only works if the stories and their contents are searchable—both for the audience and for newsroom staff, who sometimes need to find images, video clips, quotes, and sound files that were used in previous stories. Without process use of metadata and organized storage, it can become impossible to retrieve individual elements of previous stories.

But Vox Magazine’s editorial director, Heather Isherwood, pointed out the elephant in the room. With newsrooms staffed largely by students, maintaining a consistent process for posting and cataloguing stories online is a constant struggle as new students continually enter the fold while the older, more experienced students graduate and take their institutional knowledge with them. Call it a magnification of the industry-wide problem that has seen papers across the country lose decades of institutional knowledge to job cuts and wage competition from other industries.

“What we’re doing isn’t really archiving,” acknowledged Elizabeth Stephens, executive editor of the Columbia Missourian. “A lot of what we’re doing in terms of organizing stories and making them searchable goes away if we change our CMS. An archive is a more permanent solution, and we just don’t have that.”

At the same time, Mizzou’s newsrooms — bursting at the seams with student journalists at a time when even the most successful news organizations have seen their share of downsizing — present an opportunity for the experimentation and iterative approach necessary to create a comprehensive digital preservation policy.

A key part of that process will be determining what — amongst a sea of files and assets multiplying exponentially — really needs to be preserved.

“We don’t need to save every thought anyone has ever had,” said Mark Horvit, who teaches investigative reporting at the School of Journalism and directs the School’s state government reporting program. “And no matter what we save, if it isn’t publicly accessible and searchable, what is it worth? A solution needs to be realistic, and it needs to work for everyone.”

For McCain, that solution starts with using the insights gleaned from the April gathering to build a comprehensive policy around the storage and organization of everything from text files to photo captions. Such a policy will ensure consistency across platforms and ease the turbulence of constantly folding new student reporters into the system, while providing a rock-solid foundation on which to experiment with further solutions.

McCain hopes that once a policy is in place, it will not only meet the needs of the School’s newsrooms, but will serve as a model for an industry that, by and large, is too busy solving other problems to pay attention to a gathering storm that poses serious threats to more than a century’s worth of journalism and history.

“There is only so much that can be done reactively when a server crashes or an historic newspaper goes out of business,” McCain said. “Now is the time to be proactive and treat this issue with the urgency that it demands. That starts with working together, across platforms, to recognize the issues we’re facing and come up with realistic solutions that everyone can get behind.”

RJIonline will follow this project as it develops.