Photo: Franzie Allen Miranda | Unsplash

It takes real effort to make journalism inclusive

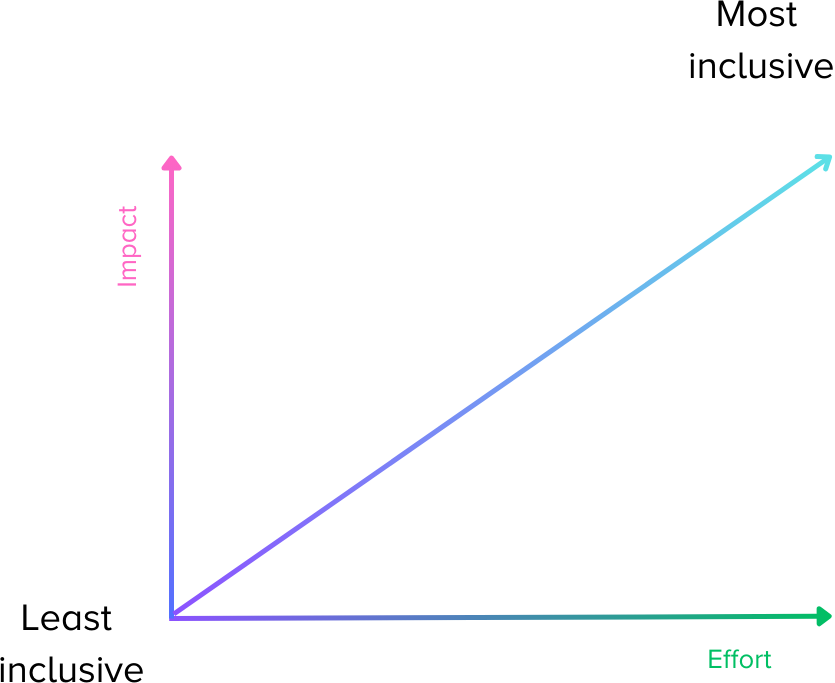

Sensitivity professionals nudge newsrooms up the effort-to-impact ramp towards inclusion

Say your newsroom has an amazing and inclusive style guide; it integrates the National Center on Disability and Journalism’s Disability Style Guide, the Diversity Style Guide, the GLAAD Media Reference Guide, and the Indigenous Journalist’s Association Reporting Guides, among others as well as your newsroom’s particulars, including notes about referring to a recently renamed street in your city, whether “jagoff” constitutes profanity, and the appropriate way to allude to a local restaurant’s most famous entrée. It all resides in a dynamic living document that your journalists update regularly in conversation with one another and a larger professional community. Phew! If you’re here already, good on you.

If not, it’s never too late to put your copy-pasting skills to work as you beg, borrow, and cite your way to a great style guide. (Be sure to check out 2023 RJI Fellow Celia Wu’s project for a style guide plugin to level up your implementation!)

But … is all this enough? Will this save you from putting your foot in your mouth? Will it keep your outlet from reinforcing harmful stereotypes? Will it change whose stories you choose to tell, how you tell them, and who you decide is the opinion of record in those retellings?

Maybe. Maybe not.

If your style guide is kept current and represents the preferences and recommendations of multiple marginalized communities, it’s an indication that your newsroom is engaged in a good faith effort to be more accurate, precise, and inclusive. But a style guide isn’t as good as best-in-class newsroom models committed to investigative social justice journalism, and it’s not as easy as sending a draft to a colleague for a “gut check” or doing a “find replace” for a problematic term. A style guide won’t catch a problematic narrative arc, a pattern of erasure, or or biased choice of sources. There are tradeoffs between effort and efficacy in the path towards inclusive journalism, and an inclusive style guide, while fairly straightforward, has limitations.

Most of a newsroom’s efforts to tell stories equitably and inclusively are constrained by the tradeoff between the effectiveness of any strategy (bots, staffing, consultants, audience canvassing, dedicated verticals) and how difficult or expensive that strategy is to implement (hours, emotional labor, money, contracts).

If we position efficacy on the a vertical axis of a chart, and effort along a horizontal one, our path towards inclusion and away from marginalization looks like a ramp*, where the harder we try, the greater the efficacy of our pursuits.

This ramp towards inclusion is one which we mostly endeavor to ascend, either for selfish reasons like audience growth and market penetration by more earning the trust of new and diverse audiences, or for moral and philosophical ones, believing that more inclusive, just, and representative journalism will change the world for the better by building a more informed, and less prejudiced society. A well-rounded newsroom carries with it both of these mindsets simultaneously, and so should be doubly invested in this work.

Here I’ll make the argument that working with sensitivity professionals results in a meaningful departure from the effort vs efficacy tradeoffs constraining inclusive journalism: With a slight increase in effort, sensitivity work provides a huge boost in the efficacy of inclusion efforts one project at a time, helping to shape best in-class outputs, while simultaneously educating the newsroom in how to operationalize inclusive practices, mindsets, and language for when reporting on marginalized identities.

But first, some rules of the ramp.

Moving up the ramp takes work

The ramp of inclusion efforts starts on the bottom left, where minimal effort results in negligible impact. The ramp towards inclusion ascends up and to the right: As we put in more effort (diversifying staff, community advisory groups), we see those efforts are more effective (e.g. more members of the community report feeling heard, a more diverse audience is ultimately served).

Examples of newsroom efforts to minimize the risk of harm to marginalized groups fall (rather subjectively) everywhere along the ramp, including complete avoidance of identity and committed traditionalism, the “least inclusive” scenarios, all the way to establishing a dedicated newsroom of, by, with, and for one or more marginalized communities. The latter describes almost every winner of the 2023 Nonprofit News Awards.

A motif that requires as little effort as avoidance, and which ultimately is as ineffective in advancing representative and inclusive storytelling is delegation.

Delegation of effort might sound like a denial due to inadequate mission-alignment or “fit.” Delegation can happen when a newsroom believes tackling issues of race, class, or disability is outside of the scope of their work, mission, or capabilities, or that doing so undermines their objectivity, preferring instead to delegate that work to newsrooms with those identities explicitly staffed and cited in their mission.

This type of delegation is rarely done in public, likely because it doesn’t require resources or relationships to abstain from a responsibility (quite the opposite). The confidential nature of those discussions may also reflect a modicum of shame or internal conflict over what should and should not be reported.

However newsrooms that are newly owning responsibility to issues of identity and equity are oft-riddled with novel funding opportunities, CEO letters or Editor in Chief interviews, and new collaboratives.

The conspicuousness of any newsroom reclaiming responsibility for journalism at the intersection of identity and literally anything else is an indication that real effort and resources have been applied to make good on that commitment — it is a significant move up the ramp.

Newsrooms should intentionally move around the ramp

Any newsroom with limited resources (i.e. every newsroom) should move with intention all over the ramp, side to side and up and down.

Every story, project, process, or even hire carries with it a different amount of risk of harm to minoritized and marginalized communities, some much more than others. Some pitches also carry an outsized opportunity to benefit those communities! Even best-in-class shops with a proven record of equitably representing the lived experiences of one marginalized identity may find that they encounter a massive wall of effort in order to accurately and inclusively represent the intersection of that identity with another.

Conserving attention, effort, emotional labor, and freelancer funds for projects that disproportionately feature, represent, affect, or risk harming any marginalized community allows resource-strapped newsrooms to capitalize on those opportunities, preventing the greatest harm, maximizing social good, without burning out their staff or their bank accounts. This is intentional side to side movement along the effort axis of the inclusion ramp–intentional resource management.

Innovation and operationalization of inclusive tactics characterize vertical movements on this effort vs efficacy landscape. Integrating inclusive style guides is easy enough, and may lead to more trust and attitude change than arguments offered in non-inclusive language. Even one staff member’s addition of an ableist language bot to my workplace Slack did quick work to re-socialize me and my colleagues away from harmful expressions in our day-to-day messages, the impact certainly extended to our content. Heavy lifts, like establishing new roles to support inclusive journalism, building new relationships in the community, or establishing a source auditing protocol might be hard at first, striving deep along the effort continuum, with significant, if delayed, impact.

Trouble finds newsrooms who move about this space in a less-than-thoughtful manner. Performative efforts that don’t work to make newsrooms more inclusive, may doubly alienate minority-identifying staff, further fueling a biased departure from the field of journalism (a significant loss to the professional community, audiences, and society). Mistakes also occur which actively exclude communities, such as breaking news coverage that broadly misrepresents indigenous communities or a story about a new medical advancement that simultaneously dehumanizes people who are autistic.

Enter sensitivity professionals: Experts at moving up the ramp

Sensitivity professionals — also called sensitivity readers and cultural consultants — are professionals who work to prevent or reduce the further marginalization of one or more identity communities in mass communications. The work of a sensitivity professional can exist anywhere within the effort and efficacy landscape, but generally results in more inclusive outputs. The work can include everything from flagging harmful or excluding language, to educating journalists about destructive narratives and stereotypes, even extending to thoughtful sourcing, channel selection, and strategies for identifying and debunking prevalent misinformation about a community.

What is particularly powerful about sensitivity professionals though is that they offer a rare opportunity to escape the effort-efficacy tradeoff, particularly for small newsrooms–they make it easier to do better, usually with lasting benefits and limited resources.

Sensitivity professionals are often contracted in a freelance capacity. Most newsrooms build freelance dollars into their annual budget, and can commission sensitivity work using existing editing, producing, or consulting contract language without any added overhead or lawyering.

Sensitivity professionals are also experts in their own right. They are often journalists or scholars, they co-identify with the community of interest, and they have a multi-year track record of providing consulting services on a particular identity. The expertise of a sensitivity professional can be sufficient to fully undermine any argument in favor of delegating difficult stories to dedicated outlets by leveraging their years of experience.

It’s worth noting here that not all sensitivity professionals are individuals — some newsrooms function in a capacity that is analogous to a sensitivity consultancy in reporting partnerships (e.g. Block Club Chicago and Borderless Magazine’s collaboration covering the experience of Venezuelan migrants sent to Chicago from Texas as a part of a political stunt). Reporting collaboratives can pool channel and sensitivity expertise in order to respectfully report on, with, and for marginalized communities.

Even research and sourcing activities become more efficient when supported by an expert who is well connected to a particular identity or community. They can recommend trusted organizations, researchers, experts, and advocates for marginalized communities, arenas and contexts where relevant sources might be more or less receptive to an approach by the press, and educate journalists on the types of concerns and expectations (for example, the unique considerations when reporting on unhoused communities) that need to be addressed before an approach might be considered in good faith.

Perhaps the most convincing argument to leveling up with sensitivity professionals is the potential to create lasting change. Speaking from my own experience in interacting with, and observing the work that develops between Science Friday’s journalists and sensitivity professionals, the changes to how we do our work are lasting. We learn alongside one another, practices extend to other roles and to leadership, and rubs off on our colleagues and collaborators, even when direct interactions with a sensitivity professional might be as little as a single email thread and one 45-minute conversation or as long as a year-long grant funded collaborative.

The ratio of impact to effort is massive — with every interaction we are more likely to pursue collaborations in the future that center equitable representation and reduce harm.

*When presenting some of this work at the 2023 Inclusive Science Communication Symposium, it became immediately apparent that my former choice of a staircase analogy for this idea of the tradeoff landscape excluded people who don’t use stairs. Ramps are awesome, not only because most folks can use them, but because they provide a superior analogy–the path to inclusion is continuous, and almost never occurs in discrete steps or achievements, and we can easily slide backwards. Thanks to the Inclusive Science Communication community for bringing this to my attention.

Comments