Aerial view of Guajataca dam in Isabela, Puerto Rico, after it threatened to collapse due to the impact of Hurricane Maria. Photo: K.C. Wilsey | FEMA

What radio amateurs and journalists have in common during natural disasters

Fact-checking, fighting misinformation, and spreading key information in the aftermath of a disaster

Communications are always among the immediate needs in the aftermath of a natural disaster and recovery efforts, and local radio amateurs often show up like journalists. They are both part of an informal net of first responders, even though neither are formally recognized as such.

Both journalists and ham radio operators quickly set up their equipment to exchange and share vital information across the regions affected. It happened in Puerto Rico in 2017, Fort Myers in 2022, and Maui last month.

William Planas has 10 years of experience as a ham radio operator and 31 serving in the Army as a State Spectrum Manager. For him, volunteering during natural disasters is the best way to give back to the communities in Puerto Rico, where he lives.

When asked what would be the first thing a journalist — or anyone — should do to learn more about getting involved in ham radio service, Planas is clear: “Listen, you always have to listen. A lot of people talk about ham radio, but I tell them to first listen to what it entails because maybe – after they listen – they might realize it’s not what they thought it was. I’ve always believed that people should listen and get involved where hams already are to know what this hobby entails. Part of this hobby is helping communities and citizens,” says Planas, whose ham radio license is NP3WP. Those letters and numbers are equivalent to a driver’s license number, showing the ham radio operator is licensed to do the work.

In 2017, after Hurricane Maria left most of the 3.7 million residents without power and 95 percent of cellular sites were out of service, Planas made his radio station at home available to neighbors to help them contact family members in the United States and on the other side of the island to let them know they were okay.

Like him, reporters in my newsroom who had been deployed all over the island were getting the same request. They were collecting names and landline numbers to call family members and friends and let them know they had survived. Once they returned to the newsroom, we designated a group to call those relatives. It was a primitive person finder system that we could have expanded through ham radio operators.

“We can also pass messages, called traffic, with emergency information to the different municipal emergency management stations. We help governments to channel these emergencies. Many times, it takes time for help to arrive. By sending these messages through the radio, we help them prioritize different emergencies,” Planas explains.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, newsrooms also supported local and state governments in Puerto Rico. Three days after the storm hit the Island, the Gujataca dam threatened to collapse. The force of the water that reached the dam during the storm had caused damage to three plates located in its spillway and caused two cracks. People living near the dam were at severe risk, and the central government at that time contacted our newsroom to help them spread the evacuation alert and let people know where they could find refuge.

“Everyone can hear everything that is transmitted on air. That’s why it’s important that even when we transmit emergency information, we listen first,” Planas says.

How it works

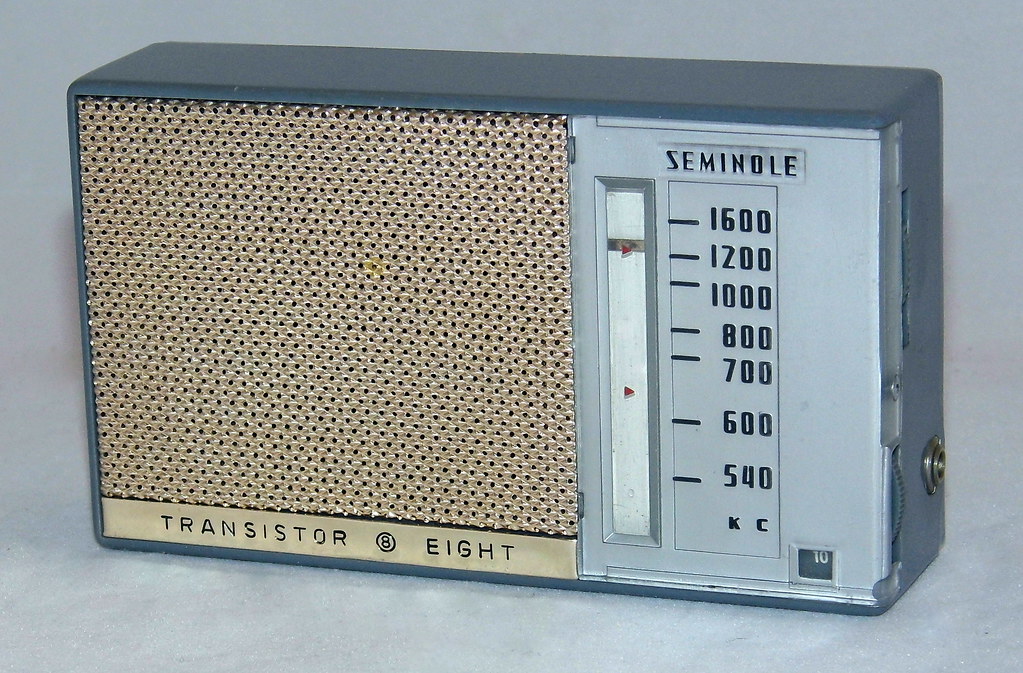

Looking at the dial on an old AM radio, frequencies are marked from 535 to 1605 kilohertz. This is one radio “band.” Radio amateurs have 26 band frequencies they can use, and anyone with the right equipment can listen to what they say. That’s why precision is key for Planas and radio amateurs, especially when involved in emergency communications.

The Ham radio service is regulated by the Federal Communications Commission, which allows journalists to listen to amateur radio frequencies and use that information in their reports, among other things. But most of the time, journalists focus on interviewing the radio amateurs instead of partnering with them. Which is what my project at RJI is striving to change.

The role of Ham radio is key in natural disasters as it allows people to communicate over long distances without the internet or cell towers. Ham radio is all about independent communication and self-reliance. (BTW, the term “HAM” denoted the designated call sign of the initial amateur wireless station operated by members of the Harvard Radio Club. This station was established by Albert S. Hyman, Bob Almy, and Poogie Murray, who initially christened it “Hyman-Almy-Murray.”)

The way radio amateurs ensure, like journalists, that the information they transmit adheres to the highest standard and fights misinformation is simple but effective.

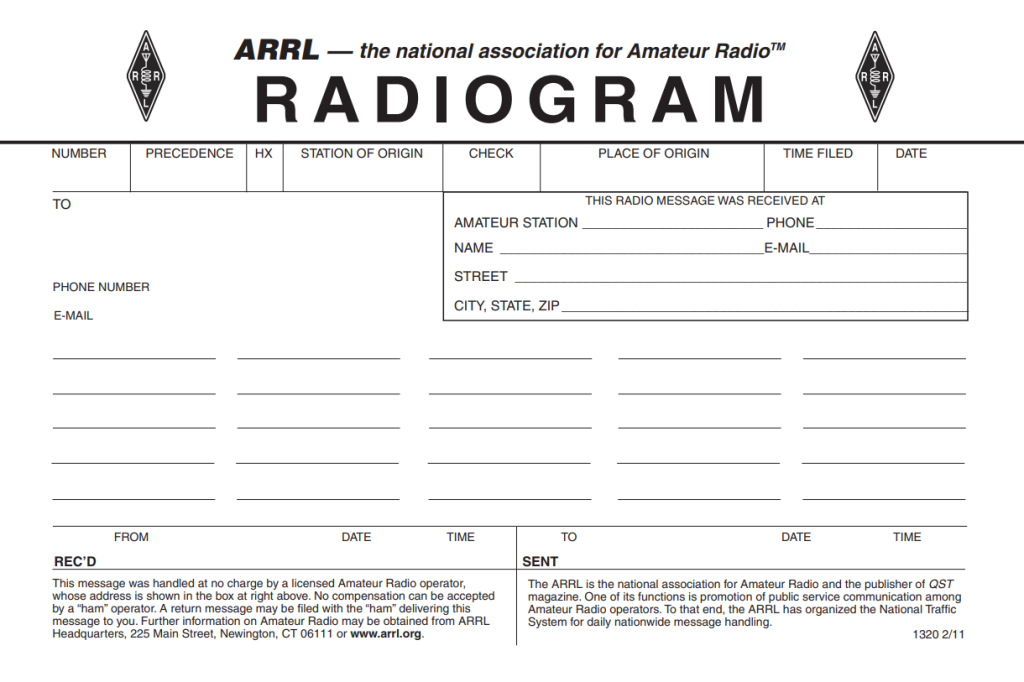

“We use what is called radiograms. It is a form in which, before sending any information, we write it down in it. Then, we read it back to the sender to check there are no mistakes or that we are not adding or subtracting information from the message,” Planas explains.

These radiograms allow radio amateurs to have physical records of the messages they receive to guarantee they are transmitted exactly as the sender intended. For journalists, it would be like using their notebooks to double-check accuracy.

“We transmit up to two or three times the same message, and we ask the other person to read the message back to us so that we can corroborate that what they wrote is a copy of what I transmitted. ‘I sent you 25 words, so in the body of the message, you must have 25 words’. Those words are written down in the radiogram form,” Planas says.

Radio amateurs do fact-checking like journalists. What ham radio operators do differently is conduct drills and prepare for the worst. They gather together in radio clubs, run exercises, and rehearse. While living in Michigan at the beginning of this year, I learned about a drill where radio amateurs simulated a flood due to a dam collapse that forced people to take shelter in a school.

The hams were tasked with transmitting how many cots and hot meals would be needed for these families to spend the night in the shelter. The drill got more complicated when ham radio operators discovered that among the refugees were vulnerable people who needed prescription drugs that were difficult to read and pronounce. It was crucial for them to practice the phonetics of the names of the medicines in order to transmit them correctly. If it had been a real case, as in Puerto Rico, journalists could have been listening to that radio frequency and could have helped amplify the needs of the community.

No one from the newsroom was there before, but maybe now reporters will be there practicing along with other hams next time.

PS: The intervention of the US Corps of Engineers, which installed 10 dewatering pumps to lower the water levels in the dam, among other measures, avoided the collapse of the Guajataca dam.

Comments