Photo: Jakob Owens on Unsplash

How to avoid publishing misleading photos

How trustworthy is the source? How high are the stakes?

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Reynolds Journalism Institute or the University of Missouri.

One of the many challenges journalists face in the misinformation crisis is in images. As storytellers, we circulate an enormous number of images daily — online, in print, and on TV. This gives us a large risk for inadvertently spreading misinformation through inaccurate or misleading photos.

How do we make sure we don’t spread misinformation when we’re busy churning out multiple photos, stories, graphics and pieces every day?

When you need to vet photos, I recommend First Draft News’ guide to online verification. It goes over what First Draft calls the “Five Pillars” of verification: source, date, location, motivation and provenance.

Provenance means the origin of the photo — who exactly took it, and where did it come from. Shaydanay Urbani, partnerships and programs manager at First Draft News, said provenance may be the most important aspect of verification, because it provides so much valuable context. For example, make sure you aren’t confusing a “verified source” with a verified social media account — they are very different things.

Urbani also recommends a browser extension called RevEye as one small step that can have a big impact. RevEye searches for websites where a photo has already been published, in what is called a reverse image search. “The great thing about a reverse image search is that it takes 10 seconds,” Urbani said.

In fact, RevEye combines searches on Google Reverse Image Search, Yandex and TinEye, some of the most widely used tools available. That’s why, Urbani said, installing it as a browser extension can save you so much time. RevEye was designed for Chrome, but can also be installed on Firefox, Microsoft Edge, Opera and other browsers.

Another plugin called InVid, which does a similar job of searching for an image across several search engines, also comes highly recommended by investigators who use these tools. If you’re new to reverse image searching, the Google News Initiative includes an excellent short tutorial as part of its verification training track.

This can help you find the origin and context of a photo, or even just reveal that something you thought was new has actually been published before. Many photos, though, deserve even closer inspection.

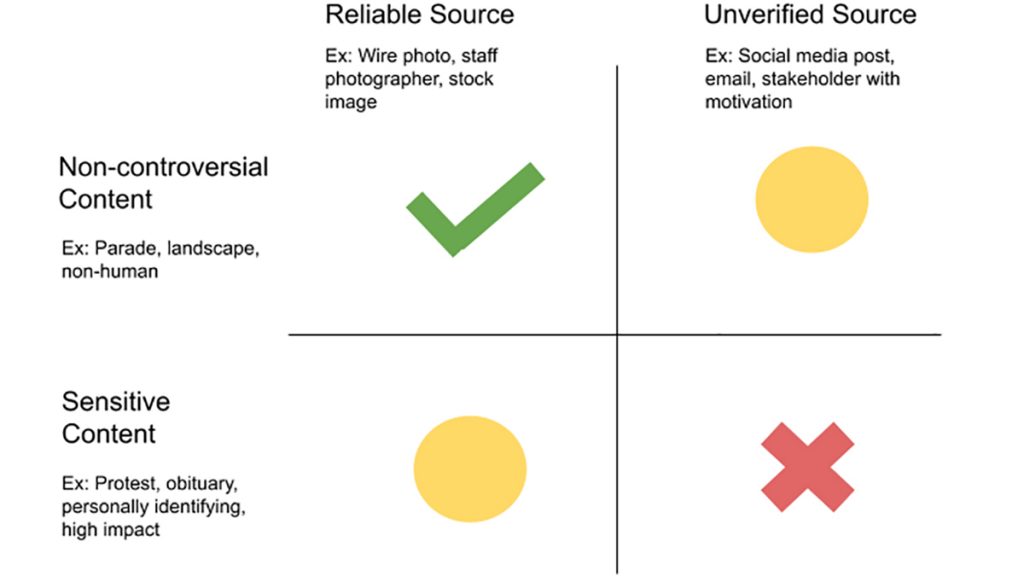

Often, the scale of how fully to vet it comes down to two broad questions: how trustworthy is the source, and how high are the stakes? To streamline the decision making process, I made a very simple chart called an Eisenhower Box.

The yellow circles mean, “Stop and think.” Should you publish this photo? Should you vet it first?

The red X means, “Stop!” Do not publish this photo without verifying it, or do not publish it at all.

The checkmark means, “Green means go.” You can be reasonably confident in the truthfulness of this image.

A reliable source is one that you, as a journalist with a seasoned news judgment, don’t have much reason to question. A good example of this would be your staff photographer or Getty Images.

Unverified sources, unfortunately, comprise most other sources: social media posts, pictures sent by readers, or someone with a motivation to provide a certain narrative.

Here’s an example: Let’s say an AP photo comes across the wire, showing an enormous Elmo balloon in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. This is a) a reliable source and b) noncontroversial content, so it’s a green light on both counts.

Another example: Someone tags your newsroom in response to a tweet showing a man struggling in the arms of two police officers. The officers seem to be pinning him to the ground, and the tweet states that this happened at a protest in your city last night.

This photo gets a red light on both counts. You don’t know the source of this video, nor do you know the full story of what’s going on inside it. Your action should be to verify the photo as much as possible before running it.

This should include at least a few of these steps:

- Reverse image search;

- Looking up the user’s Twitter bio and DMing them to ask where the content originated;

- Looking at the photo’s metadata;

- Calling the police PIO or filing a public records request.

If you don’t have time to do all of these, or at least most of them, do not release the image until you do. On the other hand, you don’t need to devote as much time to verifying the parade photo as you would this one, because that wouldn’t be a good use of time.

As with all ethical questions, these situations can feel like they need a discussion among many in your newsroom. What one editor thinks is a controversial subject, another might not. Try to use your most strict news judgment. If you need a tiebreaker, ask yourself, “What is the worst case scenario? Could this cause harm?”

For the situations above, what is the absolute worst outcome that could come from you publishing the photo? For the Thanksgiving Day parade, for instance, it could mean issuing a correction in your paper.

For the arrest, it could mean someone getting prosecuted, evicted, harassed, or attacked. It could mean affecting local policy, committing defamation, alienating community members, or contributing to prejudice or false narratives.

Another thing to keep in mind is that personally identifying photos are some of the most high risk, Urbani said. “Those can be extremely harmful for the person who’s depicted,” she said. “It’s your duty as a reporter to keep people safe.”