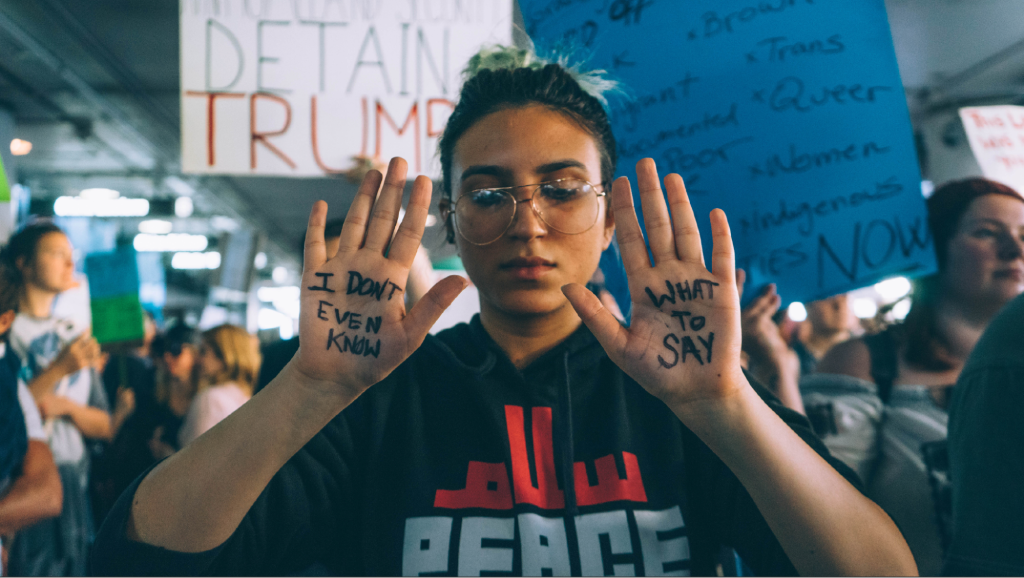

In June 2020, a group of about 250 activists attempted to topple the Andrew Jackson statue in front of the White House. Photo: Jen Byers

Reporting in spaces of civil unrest

How your approach to public engagement impacts your safety profile

The Global Peace Index of 2021 cited a 10% increase in civil unrest globally in 2020, where the world population saw nearly 15,000 demonstrations. Over that time journalists were called on to cover protest movements from Black Lives Matter in the U.S. to farmers in India, anti-extradition protests in Hong Kong, and anti-government uprisings in Puerto Rico. This trend of increased civil unrest continues with massive movements in Iran and China as 2022 comes to a close.

Reporting on civil unrest is increasingly dangerous to news media as public trust and government support of a free press wanes in many nations. The risks of protest reporting are especially high for visual journalists whose camera gear unavoidably heightens their visibility as news media.

The dangers journalists face while reporting on civil unrest come from all sides: police and other government agents who utilize ballistics, tear gas and kettling for mass arrests; armed counter protesters; and media-wary or explicitly press-hostile publics. In environments such as these, which will likely continue to be the norm for many years to come, there are key safety practices journalists can become familiar with to manage risk and increase security.

TIP: It’s imperative to discuss team communication protocols and back watching prior to arriving at a protest, rally or other environment where the potential for civil unrest is high. Can you report in teams of at least two, especially if you’ll be looking through a viewfinder or wearing headphones for audio capture? Is there a person in a newsroom or other offsite location nearby that can be a check-in on your safety? Do you have access to foundational personal protective equipment (PPE) gear such as helmets, eye protection and gas masks? Try to also have a basic first aid kit on hand in the event of tear gassing, minor wounds or other medical emergencies.

While each of these considerations are useful to lessen risk, they rely on a certain level of access to resources, gear and other individuals for safety support that aren’t always possible even for well-resourced news organizations and are a rarity for most independent and student journalists. What if you’re reporting solo and have no person to watch your back, much less a newsroom to report back to or rely on in the event of danger? Even if you have access to a first aid kit, what if you aren’t trained in applying a tourniquet, using medical gauze, or responding to tear gas injuries?

One of the biggest components of our safety is how we engage the communities within which or about which we are reporting. When you are without the resources, official backing and team support of a major news organization, it is often the protestors themselves who will be your support in a crisis and your first line of defense against severe dangers. This idea is often antithetical to how journalists are taught to think about sources or the people in their stories but recognizing yourself as part of the protest environment rather than above or apart from it puts you in a position of increased safety as well as being more trusted by those whose stories you hope to tell.

Jen Byers, a former video news producer for Al Jazeera and current Investigative Journalism Fellow at USC who goes by she/they pronouns, says this has consistently been the case for them in their work documenting dozens of protests in and around Philadelphia. They also integrate informed consent practices to build community trust and make intentions clear from the beginning. “Leading with consent and permission is a really big thing that has kept me safe,” says Byers. “It has also allowed me to be in communities with longevity and gotten me invited to future events.”

That relationship-building with people — such as not bringing a camera out until people feel comfortable and understand more of who a journalist is — improves all aspects of the journalist/source engagement. Byers tries to avoid having to make new connections at every event, saying “that makes me safer if I’m being referred to my next job by my last source with ‘oh you’re so and so’s friend?’ then that mitigates a lot of harm.”

Having worked with a multitude of different groups as a citizen documenter, community advocate and independent journalist before being a staff video producer for a global news organization, Byers learned that a major source of the disconnect between communities and the press is an aggression coming from their perspective of “‘who are you and why are you here?’ So, if you can get rid of that you’re starting fifty percent safer than you would otherwise. Leading from consent is also just a restorative journalism process.”

That restorative component is fundamentally connected to a journalist’s safety in civil unrest, conflict zones and other dangerous reporting environments. Recent discussions of how journalists might navigate consent during protests has proven controversial for some media practitioners who want to maintain the perceived sanctity of first amendment freedoms, especially as a free press is increasingly constrained.

Yet, the practice of informed consent as an ethical guideline for journalists working with vulnerable populations is not new, as evidenced by a 2015 World Health Organization briefing and 2016 white paper by the United Nations, both on consent practices in photography. Pushing back against some of journalism’s historically extractive practices is at the core of contemporary critical media approaches like movement journalism and restorative narratives. These different frameworks for thinking about the work of news media and documentary intersect with journalist safety because people who trust their news media to tell authentic, thoughtful stories from a place of care are not a threat to individual journalists and can actually be a refuge in moments of danger.

For Byers, the pre-work of making connections prior to showing up to report on civil unrest is key to being successful, maintaining your safety and being conscientious about how you engage communities. “The biggest thing that I want to say is that you cannot expect access with people you don’t know, if you’re meeting them for the first time at a site of conflict. The U.S. media has consistently gotten the stories wrong about protests, it has historically been so horrific that a lot of people are not going to want to talk to you.”

TIP: One major thing to keep in mind is your attire: “If I’m going into a community that poses danger to someone like me as an LGBTQ+ journalist, I try to dress the part,” they say. “I’m dressing in a way that will lower my profile, a sort of social camouflage, thinking of what outfit I can wear that will make me be seen as neutral as possible.” Byers recommends pulling from your own wardrobe and finding something aligned with an outdoor working class aesthetic that will prevent you from being immediately Othered in the context of protest groups. “If you show up to the Trump rally in a new Patagonia jacket and your hiking shoes, they’re going to immediately think ‘that is a liberal, that is someone who is antagonistic to my cause.’ Working class clothes tend to cross the aisle, like blue jeans and a t-shirt,” Byers suggests.

There’s also the matter of what PPE to wear and how that might impact your profile in public spaces. Byers says they have a few essential resources at their disposal — a bulletproof vest, an individual first aid kit, basic safety training and weapons training.

“Having safety gear helps you feel more safe and confident, being more confident helps you appear more secure outwardly,” says Byers. Which is important, because “if you show up secure, confident and aware but not scared, you’re less likely to get hit. If you are aware of how you fit into these ecosystems and are thinking about what you can do to fit in” that will go a long way to improving your overall safety.

With that in mind, they recommend these gear considerations:

- Individual first aid kit (IFAT) with chest seals, tourniquets, bandages and gauze, surgery scissors, everything you need to dress a gunshot wound and a heavy bleed.

- Bulletproof vest: “For plates, I recommend ceramic over steel. And L210 special threat plates are good to look into. I personally have soft 3A plates and ceramic level 4 plates.”

- Eye protection

- Jugs of water and Maalox in case of teargas

- Helmets, especially if reporting at night

- Shoes you can comfortably run in

- In dangerous situations a lighter kit is better than a heavy kit i.e. you don’t need to carry all of your lenses

- Consider the delicate balance of having your gear available vs. wearing your gear because that will impact your profile. “You don’t want to show up looking like Rambo. So maybe consider having it in your backpack or wearing a plate under a shirt, etc.”

The reality is many journalists will not have access to the often costly gear described here, especially those working independently or student and self-taught journalists freelancing early in their career.

In the absence of expensive gear, a reporting team, organizational support and other professional resources, the things that will keep you safe are general situational awareness and showing up authentically and thoughtfully to the communities you’re working alongside. Building public trust by informing sources about who you are, what you’re doing and why you’re doing this work is one of the most important things a journalist can do to mitigate elevated risk in a civil unrest environment where emotions are heightened and distrust of news media is pervasive.

Resources

As part of my work on Source of Safety, I am offering weekly listening sessions so that journalists around the world can connect with me directly to talk about their experiences with professional hazards, safety concerns and risk management needs. If you’re interested in talking about any element of safety and security for visual journalists, please schedule a meeting with me here.

Take the Safety Survey: Part of this project is trying to assess the safety and risk management needs of visual journalists around the world. Please take this survey to offer your thoughts, experiences and what you want to see taught in journalism safety training!

Follow us on Twitter and share your safety tips, gear and anecdotes from on the ground experiences using #sourceofsafety

I have put together a list of readings and an accessible Google Drive of resources that will be continuously updated over the course of this project and beyond. Please email info@sourceofsafety.org if you have any suggestions for guides, checklists, reports, templates or anything else to add to these living resources.